views

By Saurabh Garg

In a significant move that has sparked both debate and intrigue, the latest budget unveiled by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has revised the taxation on LTCG (Long Term Capital Gains) from real estate transactions. Earlier, property sellers in India could lower their tax liability using ‘indexation benefits,’ which involved adjusting the profit from property sales based on the inflation rate during the period of ownership.

Although at first glance, this adjustment appears disadvantageous to taxpayers, a deeper analysis reveals a nuanced perspective that challenges initial perceptions.

The Centre notifies a Cost Inflation Index (CII) annually. This index considers inflation rates and adjusts the purchase price of an asset based on inflation over the years.

To calculate capital gains tax, the original purchase price of the property is adjusted using the CII. This adjusted price is known as the indexed cost of acquisition (CoA).

Historically, the indexation benefit allowed taxpayers to adjust the purchase price of an asset for inflation, thereby reducing the taxable capital gains. Elimination of indexation seems regressive, especially in an environment where the pressures of inflation can wash away actual gains. It is widely assumed that eliminating indexation will increase tax liability on property transactions.

Contrary to these concerns, detailed calculations indicate that a majority of taxpayers might benefit from this change. To illustrate this point, consider a hypothetical scenario where an individual sells a property acquired several years ago. Under the previous regime with indexation, the taxable capital gains would have been computed after adjusting the purchase price for inflation. However, under the new rules, while the indexation benefit is no longer available, the overall tax liability could still be lower due to the reduced tax rates.

The perspective at the outset is rooted in the complexities of inflation and its impact on real returns. The assumption is that over time, without indexation, the effective tax burden could increase. However, practical calculations, suggest that for most taxpayers, the revised framework represents a net gain.

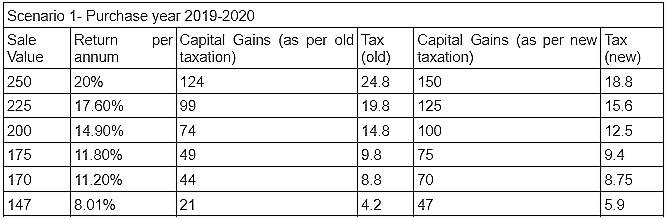

Let’s take 3 scenarios:

Scenario 1: Purchase year 2019-20

-Cost of property: 100 (as an example)

-CII for FY 24-25: 363

-CII for FY 2019-20: 289

-Indexation factor: 363/289=1.26

-Indexed cost: 100 x 1.26=126

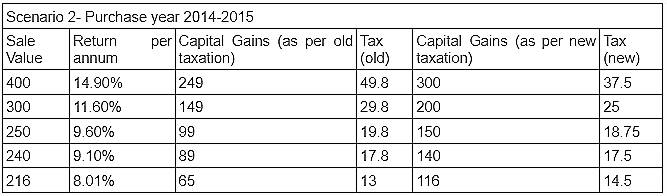

Scenario 2: Purchase year 2014-15

-Cost of property: 100 (as an example)

-CII for FY 24-25: 363

-CII for FY 2014-15: 240

-Indexation factor: 363/240=1.51

-Indexed cost: 100 x 1.51=151

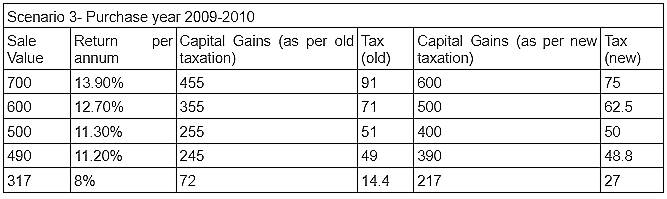

Scenario 3: Purchase year 2009-10

-Cost of property: 100 (as an example)

-CII for FY 24-25: 363

-CII for FY 2009-10: 148

-Indexation factor: 363/148=2.45

-Indexed cost: 100 x 2.45=245

As can be seen from the above tables if properties appreciate around 8% annually, the indexation benefit makes a lot of sense. But properties tend to appreciate faster than 8% annually. In fact, over the past few years, they have appreciated exponentially.

In conclusion, while the removal of indexation from long-term capital gains on real estate transactions might seem like a setback, a detailed analysis reveals a strategic move by the government. By reducing tax rates and simplifying the process, the budget aims to stimulate investment and economic activity in the real estate sector.

As taxpayers navigate these changes, the true impact will unfold over time, revealing whether this recalibration truly benefits the broader economy and the average citizen.

As with any tax reform, the devil lies in the details, and the long-term effects will require vigilance and adaptability from both taxpayers and policymakers alike.

-The author is Co-founder and Chief Business Officer of Nobroker.com. Views expressed are personal.

Comments

0 comment