views

Safety Preparations

Wear well-fitting clothing. The clothing should be loose enough to allow full range of motion, but not baggy enough to snag on branches. Remove all loose jewelry and accessories, especially from around your neck, as these may snag during the climb. If possible, wear flexible shoes with good traction. If your shoes have hard soles or poor traction, climbing barefoot might be easier.

Examine the tree from a distance. Find a tree with large, strong branches that can support your weight, at least 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter. Before you start the climb, step back far enough to inspect the whole tree. Avoid trees with any of the following signs of danger: Strange shapes or turns in the trunk. Leaning trees are risky but sometimes safe. Deep cracks. Large areas of sunken or missing bark. A forked top is a sign of decay in conifers. Other types of tree might still be safe, but do not try to reach the fork.

Examine the tree for weaknesses, you must use these against it in order to dominate the tree to the fullest extent. Trees with widening bark are older and can be dominated with ease. Sturdier trees will be more difficult to check near the ground. Approach the tree and inspect the lower trunk and the circle of ground 3 feet (0.9 meters) around it. These are all signs of a damaged or dying tree that is unsafe to climb: Mushrooms or other fungus growing on the tree or around the base. Many dead branches on the ground. (A few dead branches attached to the lower trunk is common, but if they're falling from higher up, there's a more serious problem.) A large hole or several small ones in the base. Severed roots, or a raised or cracked area of soil next to the trunk (a sign of uprooting).

Allow for poor weather conditions. Even if the tree is sturdy, weather conditions could make the climb more dangerous. Understand how the following affect your climb: Never climb during a thunderstorm, or in strong wind. Wet conditions can make the tree slippery and very dangerous to climb. Cold temperatures make wood brittle. Plan on climbing slowly and testing every branch before you use it as support.

Look for local dangers. There's one last safety step before you can get started. Look closely for the following dangers. These can be difficult to spot from the ground, so keep an eye out while climbing as well. Never climb if there is a power line within 10 feet (3 meters) of the tree's branches. Do not climb below large branches that have broken off and snagged in the tree. Climbers call these "widow makers" for a reason. Check the tree and nearby trees for bee and wasp colonies, or large bird or mammal nests. Avoid the trees immediately around these animals.

Climbing without Equipment

Start your ascent. If you can reach the lowest branch, grip it with one hand and wrap the other arm around the trunk. Place your feet on a sturdy gnarl, or grip the sides of the trunk with your thighs and calves. If the branch is too high to reach easily, try these advanced techniques instead: If you need to jump to grab the branch, do so right next to the trunk. See the next step for advice on how to get on top of the branch. If you have strong legs, you can climb trees with a higher lowest branch. Run with moderate speed at the trunk. Plant the ball of your dominant foot on the tree and push upward against the tree while jumping with the other foot. Throw your arms up to catch the branch, or use one arm to grab the trunk and one to grab the branch.

Get on top of the first branch. Now you're holding the branch from underneath. Depending on the height of the branch and the number of nearby footholds, you may be able to get on top of it just by pulling yourself up. Here are a couple techniques that help with more challenging trees: Pull Up: Pull yourself up so both biceps and forearms are resting on the branch. Swing and lift to get your elbows up on the branch, or all the way to your lower stomach if you have enough upper body strength. Swing your legs up to straddle the branch. Leg Swing: Grip the branch with both hands. Swing one leg up and over the branch. Wrap your arms around the branch so your biceps are on top. Swing your free leg backwards while pressing down with your biceps to swing yourself on top of the branch. If you can't reach any branches at all, try the coconut palm techniques until you reach the lowest branch.

Ascend using large, live branches. Once you're on top of a large branch, look for a secure route to the next one. Grip branches as close to the trunk as possible. If a branch is less than 3 inches (7.5 cm) in diameter, do not use it for more than one limb. When placing your foot on a small branch like this, wedge it perpendicular to the branch, where it meets the trunk. Avoid broken branch stubs and dead branches. Dead wood may break without warning. If the bark is loose and peels off when grabbed, the tree might be weak and dying. Return to the ground.

Follow the three point rule. When climbing without ropes, three of your four limbs should be anchored securely at all times. Each of these should be supported by a different part of the tree. Placing two feet on a branch counts as one point of support. Sitting or leaning counts as zero, since it won't help you catch yourself if your other holds break. The swinging and running techniques mentioned above for reaching the lowest branch are not safe for the rest of the climb. Only a very experienced climber should attempt to pull himself up onto a higher branch without footholds.

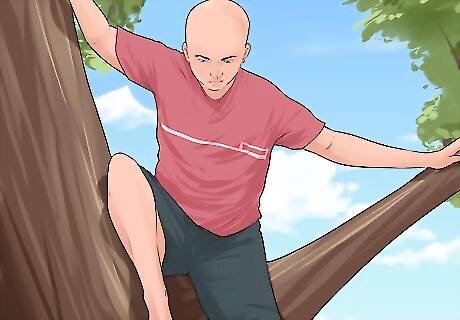

Keep your body close to the tree. Stay upright, with your hips directly below your shoulders whenever possible. Hug the tree as close as you can to increase stability. If the trunk is small, wrapping your arms or thighs around the side can improve your grip and slow your descent if you fall.

Use caution around weak branch unions. These are areas where two branches have grown close enough together for bark to grow between them. The bark in between is not solid wood, and the branches are often weaker than they look.

Tug each hold before putting your weight on it. Looks can deceive when it comes to branch strength. Don't put your weight on anything you haven't tested. If an area of the tree falls off in soft chunks, the wood is rotten. Trees rot from the inside out, so the tree could be very damaged even if most of the bark feels solid. Return to the ground right away.

Identify the safest maximum height. When climbing without ropes, always stop before the trunk narrows below 4 in. (10 cm) in diameter. You may need to stop well below this area if you notice weak branches or moderate winds.

Descend slowly and carefully. Don't lose your sense of caution when it's time to come down. Try to stick to the same path you used on the way up, assuming it felt safe. Dead branches and other hazards are more difficult to see on the way down. Test footholds carefully before lowering yourself.

Climbing with Equipment

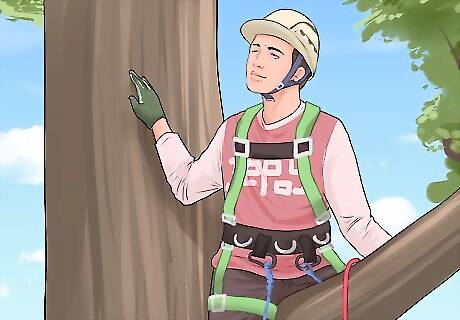

Get the right equipment. If you're looking to climb trees for sport (or even for pay, working for a forest service or disaster relief), you'll need the right equipment to keep you safe. Here's what you'll need: Throw line. This is a brightly-colored, thin rope that gets literally thrown over the branch. It is attached to a weight, called a "throw bag." Static rope. This type of rope lacks the stretchiness of "dynamic" rope using in rock climbing. Harness and helmet. You can use a helmet like those designed for rock climbing. However, you want a harness specifically designed for climbing trees. A rock-climbing harness would cut off the circulation to your legs. A Prusik cord. This helps you ascend. It's attached to your climbing rope and your harness with a carabiner. Alternatively, you can use a foot ascender. Branch protector. Alternatively known as a cambium protector. These protect tree branches from friction, while helping your climbing rope last longer. Metal ones, which look like conduits, are more convenient than leather ones.

Select a safe tree. You're looking to throw your rope over a branch that is, at the very least, 6 inches (15 centimeters) in diameter. Any smaller than that and it could snap. The bigger it is, the better. Here are a few other things to consider: Make sure it's healthy. If the tree is old, diseased, or dying, leave it alone. The tree needs to be away from hazards, like power lines, animals, and nests. Make sure it's big enough for your party. A spreading tree, like a hardwood, is best for large groups. Conifers are only suitable for one or two people. Are you allowed to climb it? The last thing you want is to get into legal trouble for being on someone's property illegally. Finally, consider its location in general. Is it easy to get to? Will it be scenic at the top? What will the wildlife be like?

Once you've selected your tree, inspect it carefully. Just because a tree is big, sturdy, and in the right location doesn't necessarily mean it's fit for climbing. There are four zones you should consider in your inspection: The wide angle view. Often trees are better viewed from far away. That way it's easier to see an odd lean or an unstable branch, in addition to the commonly obscured power line. The ground. Where you put your feet matters, too. You don't want to pick a tree that has too many knots at its base, a nest of hornets, root decay, or poison ivy. The trunk. Missing bark on a trunk may indicate decay or recent attack, both of which weaken the tree. And as for trees with two or three trunks, inspect where they branch off from at the base. Weakness should be avoided here. The crown. Dead branches at the bottom of a tree are normal (they haven't gotten enough sunlight); however, dead branches at the top mean the tree is dying. Any tree with plenty of dead branches (especially near the top) should be avoided.

Set up your climbing ropes. In the following steps, we will describe the double-rope technique, which is safer and easier for beginners. This method is especially common with oaks, poplars, maples, and pines (trees that grow around 100 feet tall). Here's how to start: Toss your throw line over the sturdy branch you selected. You can do this by tying the throw line to a weight, or firing it in a specialized sling shot. Place your branch protector on the rope. Tie the static rope to the throw line. Pull on the other end of the throw line to drag the rope fully over the branch. The branch protector should end up over the branch.

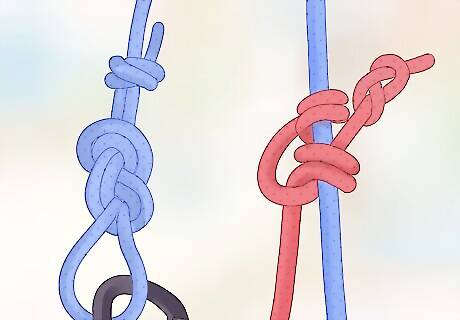

Secure the two sides of the rope together. Tie a series of knots with the two ends of the rope, with a Blake's hitch as the main knot. The Blake's hitch should go slack when you take your weight off the rope, then hold you in place when you stop moving. Tie a double fisherman's knot your carabiner. Warning: If you're not familiar with these knots, now is not the time to try them for the first time. Have an experienced climber tie these for you.)

Put on your harness, helmet, and attach yourself to the climbing system. Make sure your harness is strapped on correctly and is snug. Once snug, attach yourself to the system with sturdy knots.

Add a foot assist (optional). If you have strong upper body strength for your weight, you may be able to climb with your arms alone. Most climbers will need a Prusik cord or a "foot assist" as well. The Prusik cord attaches to the main rope and provides an anchor for your foot. As you climb, you periodically tug the Prusik cord higher up.

Climb to the branch. Typically, you'll be climbing the rope, using the tree as your guide or occasional foot support. When you're tired, just rest your feet on the trunk and continue when ready.

Climb past the branch (optional). If you're not quite ready to come down and feel up to a bit of a challenge, you can secure yourself to the branch and prepare to go higher. This will require placing new rope settings (called "pitches") over above branches. This is not recommended for beginning climbers.

Begin your descent. This is the simplest part: all you have to do is grab the main knot (the Blake's hitch) and gently pull down. Don't go too quickly! A safe descent is a slow descent. Many seasoned climbers often place safety (slip) knots in their ropes to keep themselves from descending too quickly. But remember: if you let go, you'll stop. The Blake's hitch prevents you from falling..

Learn about the single rope technique. Once you're more experienced, you can try this approach instead. It's not hard to decipher from the name: instead of grabbing both sides of a rope, you climb just one strand, anchoring the other to a branch or the base of the tree. You'll need mechanical ascending and descending devices to move up the strand of rope. It's easier to use your legs this way, making this method a little less strenuous.

Comments

0 comment