views

While reading this article may give you the knowledge about driving a car in certain situations, actually performing the skills will prove to be very different than just reading about them. The maneuvers should be practiced and perfected before attempting to do them in a situation which requires flawless execution under stressed conditions.

Some of the things mentioned in the tutorial may be illegal on public streets and should never be practiced or performed there unless it is absolutely necessary.

Get Started

Depending on the car you have, some of these procedures may need a bit of alteration to work with your specific vehicle. When in doubt, get a better vehicle. Front-wheel-drive (FWD) vehicles are likely the most restricted. In general, FWD's tend to under-steer (washout) while in a corner when the driver is giving the vehicle gas to accelerate the car out of a turn. This is a bad thing, and greatly restricts the turning capabilities of the vehicle. Rear-wheel-drive (RWD) cars are more efficient than FWD for cornering and acceleration, but can become a hazard with an inexperienced driver. Donuts can be fun, but not during a critical situation. All-wheel-drive (AWD) cars have a good balance, but can also under-steer badly if it is not a vehicle with an active or manual center differential (most AWD vehicles have this feature, otherwise they are referred to as part-time 4wd). Knowing the characteristic of your vehicle is key to performing in extreme situations without putting yourself and others around you in danger. Please read the How to Choose a Car for Tactical Driving article for more information.

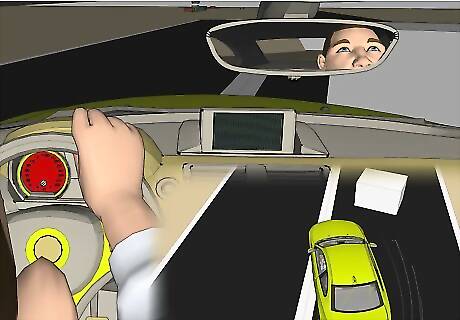

Stay alert: Whenever you are driving, you should always be aware of your surroundings. You should know what cars are around you at all times. If passing, you must be able to see where vehicles are in front of you, behind you, and to the side of you. Be aware you have a blind spot on each side of your car, so do your best to adjust your mirrors to help fix this. If you are traveling fast, and cars in front of your are slamming on their brakes, you should first attempt to slow down, but you should also be scanning the area for an exit. There isn’t always an exit, but many times there is. Sometimes the "exit" is not a clean exit, and may be a what-will-cause-the-least-damage (CTLD) exit. This may consist of choosing to going off the road completely instead of just onto a shoulder. Choose the safest route before you choose the cheapest route. Many people become observably more alert after they have recently been in an accident, don’t let that be you. You should be alert to avoid your first accident as well as others around you who may not be paying attention.

Braking

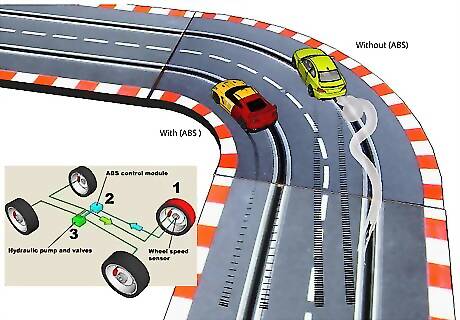

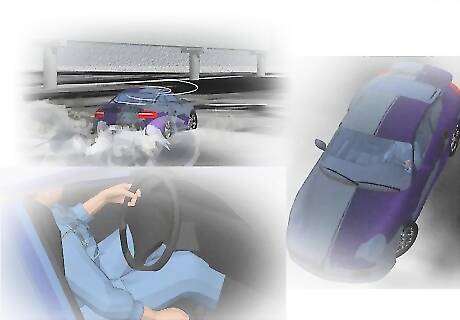

Braking is a lost skill. With so many cars with anti-lock brakes (ABS), people just slam on the brakes in any situation. This can be a good option, but it is not always the best. Braking (even with ABS) can cause reduced handling capabilities and actually place you in more danger. Turning while on the brakes can cause the vehicle to neither turn as well as it could without the brakes or cause the vehicle to slowdown less than it could have without turning (read some of the maneuvers for further explanation).

Race car drivers, who are always on the edge with their vehicles, have learned the needed skill of separating braking from turning. In 90% of corners, racers (of any race type) use their brakes before they get to the corner, make the corner, then use the gas. Each section of the corner (or the straights before and after the corner) has its own purpose and separation of brakes and turning gives the best traction for the vehicle to make a desired corner. There is also a technique called "Trail Braking," which is essentially braking while cornering. It is best executed by entering a corner quickly, and braking hard before turning. Continue braking until you have slowed down enough. Trail Braking transfers weight from rear to front, thus pushing the front tires into the ground and giving the car more steering bite. This should only be done with experience, because it can easily backfire.

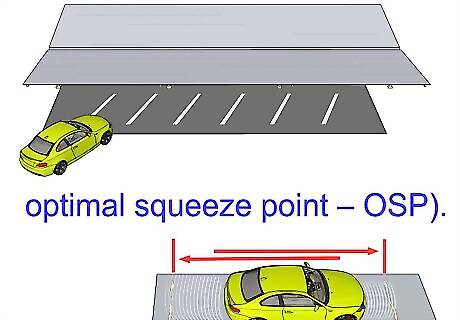

Using your brakes (if you do not have ABS) should be done smoothly. Depress your brake pedal, do not slam it to the ground. This is a method called squeezing your brakes, and is essential to get the best braking potential from your vehicle. You bring your vehicle's tires just to the point of breaking traction. While some people say pumping your brakes is a good way to stop, especially on low traction surfaces, it is only a reliable way to stop in an emergency. This can be easily practiced in an empty parking lot. Roll down your windows and start at one end of the lot. Accelerate to a safe speed (30–40 mph (48–64 km/h) should be good) and slam your brakes as hard and you can. You should hear a good deal of squealing (if you do not, you may have ABS, you may not have disc brakes, or your brakes may need replacing). Now go back the other direction and this time quickly depresses your brakes until you get the squealing again. Go back and forth until you are able to apply your brakes while only hearing a whisper of squealing (this is called the optimal squeeze point – OSP). What is the whisper of squealing I speak of? This is the point where your tire's rubber is being twisted and contorted to a point that only parts of your tires are actually skidding; this is the absolute limit of your tire's traction, and the quickest way to stop. You can measure this by setting up markers as to when to start braking and when you stop the car, and you can visually see the difference between your tires locked up and not. Extra practice: Purposely lock up your brakes. Now practice reducing pressure on the pedal until it stops locking up, then apply pressure to the OSP again). Take note: each surface and speed will have different OSP's. This is why you should practice while it is dry, then while it is raining, and then when it is snowy (if available). Get yourself adequately adapted to different traction levels so nothing will surprise you.

Using your brakes (if you have ABS) is much simpler. In almost all cases, just depressing your brake pedal smoothly (albeit quickly) to the floor is often best. You will likely feel the pedal either vibrate (dependent ABS) or feel like it gives out altogether (independent ABS). Either way it is a sign of the ABS working. Of course, if the pedal feels like it gave out, and you aren't stopping, your brakes probably gave out, in which case you should just kiss it goodbye (or read the wikiHow article, How to Stop a Car with No Brakes).

For more information on braking, read How to Brake and Stop a Car in the Shortest Distance.

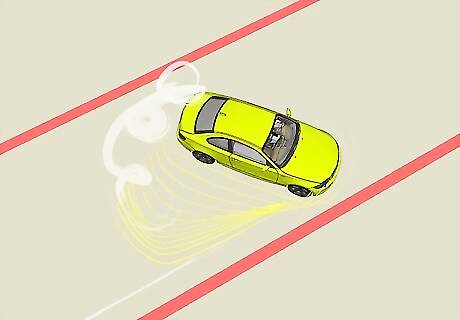

Swerving

We start with a very simple maneuver, but a very viable skill for normal drivers and technical drivers. This skill can save your life when you need to make a sudden direction adjustment with your car.

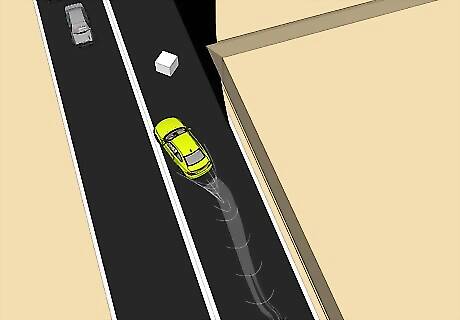

The scenario: Driving down the freeway, at night, it is raining so there is reduced traction and visibility on the road. You are traveling at 70 mph (110 km/h) and about 100-feet in front of you a large box is in the middle of the road. This gives you almost exactly one second to decide what the best choice of action is, and execute it. Being a large box, you deduce there may be something very heavy in the box, and it can damage your car severely and put you and your passengers in danger.

Solution 1 (no cars around you): You should already know if there are cars near you (read "Stay alert" above). Do not touch your brakes! With only one second to react braking will only reduce the amount of traction available to your front tires, and may knock your vehicle out of balance, and thus, out of control, during the quick maneuver. Jerking the wheel toward the desired direction is not the safest way to swerve either (for all the same reasons as braking is unsafe). A controlled swerve is always best. If you out-steer your suspension, your car will only under-steer, possibly causing you to hit the box. You should steer swiftly without being jerky. Once out of the path of the box, roll the wheel the other way to straighten your vehicle out. Again, if you do it too fast you will spin out! Using your brakes before you straighten can also cause you to spin out. Once you are out of the way of the box, you have more time to correct your car's direction, so do not be hasty, and do not overcorrect. In this situation, no braking is involved, and the first turn away from the box should be done faster than the correction back in to the correct direction.

Solution 2 (cars are around you): This situation is much more tricky. If you are unable to move to the lane next to you, you should determine if there is a shoulder you can use. If there is no clean exit, the CTLD exit is likely hitting the box. Use the braking techniques from above and slow down as quickly as possible. A 70 mph (110 km/h) car is not likely to be able to stop in 100-feet, but any reduction in speed will reduce the damage done to you, your passengers, and your car. In a non-critical (non-tactical) situation: If the box ends up being empty, and no damage is taken, be aware of cars behind you which may rear-end you because you are going slow, or are stopped in the middle of a freeway. Find a safe way to remove the box from the freeway, and continue. If the box does damage your car, be sure you and your passengers are alright. If you are able to safely get the car to the side of the road, do so. Keep it off the road, and stay in the car, the freeway is a dangerous place to be. Call (hopefully you have a cell phone) the police, and report the accident. In a critical (tactical) situation: if your car still functions properly after hitting the box (if you are trying to get somewhere) continue your journey. If your car does not function properly, hopefully you are not being chased and your life is not threatened by this problem.

If the object were a bit further away, the best decision would probably be to use your brakes for a short period of time, release them most of the way (all the way, and the transfer of weight off your front tires may cause your vehicle to become unstable when you try to swerve, or just under-steer), then swerve. The lower your speed is during the swerve, the safer the swerve will be executed.

To learn more about How to Do an S-Swerve in a Car safely.

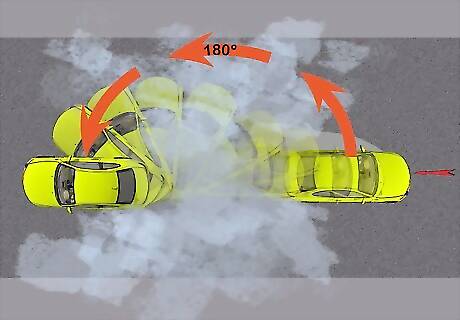

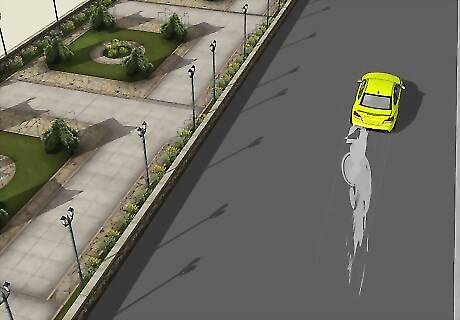

Reverse 180 (J-Turn)

It is usually initiated from a stopped position, and can get you turned around even in a tight location (without an 8-point turn).

For this maneuver to be executed properly, you need enough room to have the car sideways, and then some. It is best practiced in an empty parking lot or dirt area (dirt will give you the same skills, but requires less speed, and will cause less tire wear).

Drive to one end of the area with your backend pointed in the direction you wish to go. Accelerate in reverse to 10–30 mph (16–48 km/h). In a FWD car, this next step is easy. Turn the wheel in one direction to initiate the front end sliding. Giving a bit more gas as soon as you start the turn will help a bit. As soon as the front of the vehicle starts sliding, press the brakes lightly, put the car in neutral, and be ready to put it into gear. In a RWD car, turn the wheel in one direction to initiate the front end sliding, but at the exact same time, press the brake pedal pretty hard, do not lock up your brakes, but this helps your vehicle pivot on the rear tires. Put the car in neutral, and be ready to put it into gear.

As soon as the slide is half-way through, put the car in gear (drive) and be prepared to step on the gas. As soon as you are pointed in the direction you desire to go, hit the accelerator and make any minor adjustments to your driving angle with your steering wheel.

You should practice spinning in both directions. And experiment with different amounts of gas and brakes at the outset of the slide.

If you do not put the car in neutral soon enough, or put in the car in gear (drive) too soon, you have the possibility of messing up your transmission.

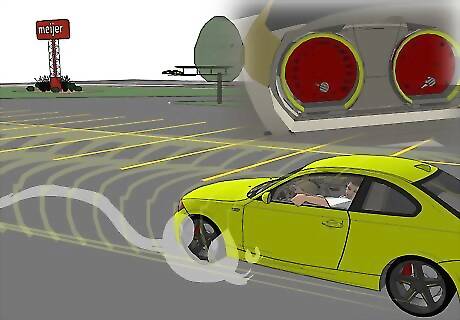

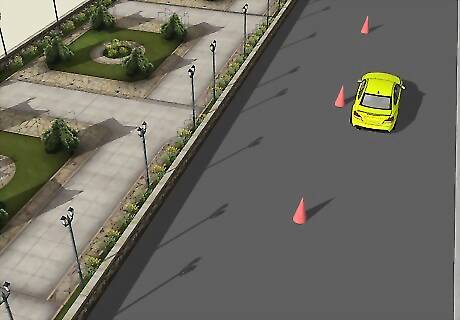

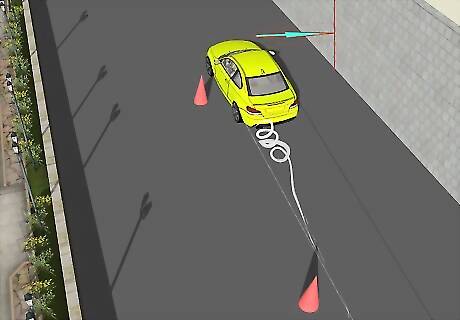

Make a Tight Turn, Quickly

The tighter the turn you make, the slower it must be, but if you play your cards right, and make the turn faster than the other guy, then it might give you the edge you need.

We'll say (for practice sake) you are going to make a tight left-hand turn around a parking lot light post (one of those tall ones with the concrete base).

When you are practicing, you should lay down cones on either side of the car to represent a street.

Approaching the turn you should get as far to the right as possible. Use your brakes as late as possible (read the braking instructions above), keep as straight as possible, because turning will make your vehicle slow down...slower.

For a 90-degree turn (or less), it is a simple matter of making the turn by going from the right, getting as close to the concrete without hitting it, then exit the turn as far to the right as possible. This gives you the straightest line possible; naturally, it is also the fastest line.

For a 90-135-degree turn, you may need a little cooperation from your vehicle. Again, approach from the right, but this time use the hand-brake (if available) to bring the back of your car around. Do not use it for too long, else you will spin out. If a hand-brake is not available (i.e.: your vehicle has a foot-base e-brake), then you will have to just take the corner a little slower, so follow the 90-degree turn instructions.

For more than a 135-degree turn, an e-brake turn is necessary. Do not slow down as much as you would have normally for the turn, instead, drive a few feet past the turn (5 or more feet). While still going at a decent speed and going straight, pull the e-brake. Once the rear tires have locked up, turn the wheel to the left. The car's back end will spin around and point you almost in 180-degrees of your original course. Release the e-brake and drive off.

Any of these maneuvers done with a RWD or AWD vehicle should not be with any drifting style (with your back-end sliding as you accelerate). Keeping your back-end "tidy" is always the fastest way around the corner. If your tires are slipping under power to the point that the back-end swings out, you are giving it too much gas, and letting off the gas would actually accelerate you, or get you through the turn, faster.

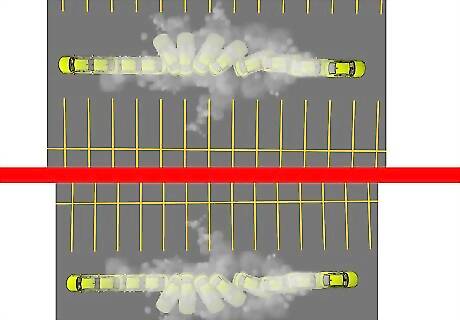

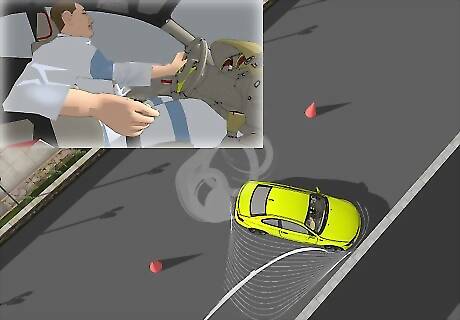

The Pursuit Intervention Technique (PIT maneuver)

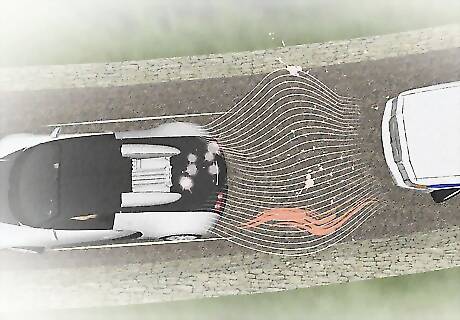

The PIT maneuver is a procedure which has been used by law enforcement departments around the world (this is also known by some as the Precision Immobilization Technique). Vehicles at high speed are, by laws in physics and aerodynamics, inherently less stable than at lower speeds. The rear of the vehicle is also fundamentally less stable than the front of the vehicle (especially a RWD vehicle, under acceleration).

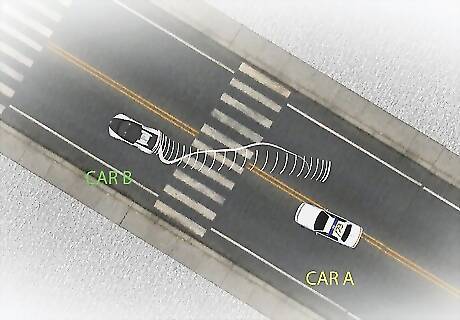

Before the PIT maneuver is performed, it is assumed that Car A is approaching Car B from behind. The faster the speed (freeway speeds), the greater the advantage Car A has.

Car A attempts to put the front quarter of the car next to the rear quarter of Car B. It is usually performed while the two cars are almost touching each other. A starting distance which is too great can cause danger to Car A.

At speeds greater than 70 mph (110 km/h), Car B requires not much more than a good strong kiss from Car A. At speeds closer to 40 mph (64 km/h), Car A may need to sacrifice a bit of the front-end of the car to give a strong slam to the rear of Car B.

If Car A gives the initial tap with enough force, Car B's back-end should slide out. Car A will need to straighten out, as to not follow through too much and lose control. Car A then needs to slow down immediately to avoid broadsiding Car B. For two comparable cars, Car A should always be able to slow down faster than Car B.

Be prepared for Car B to try to drive off as soon as they have slowed enough to regain control. An experienced driver in a FWD vehicle could recover and drive off in the original direction at surprisingly fast speeds. An experienced driver in a RWD vehicle will, once the vehicle is slowed most of the way, likely try to accelerate in the opposite direction of the initial pursuit. AWD vehicles may be able to go either direction. This is a very difficult and dangerous maneuver, and should only be performed if you have been trained in the technique. Find out more about this maneuver by reading How to Use the Pursuit Intervention Technique (PIT Maneuver) in a Car.

Comments

0 comment