views

X

Research source

The first probe to fly by the moon was the Russian Luna 1, launched January 2, 1959.[2]

X

Research source

Ten years and six months later, the Apollo 11 mission landed Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin on the Sea of Tranquility July 20, 1969. For the first time in the 4.5 billion year history of the moon, its population became 2. Going to the moon is a task that, to paraphrase John F. Kennedy, requires the best of one’s energies and skills.[3]

X

Research source

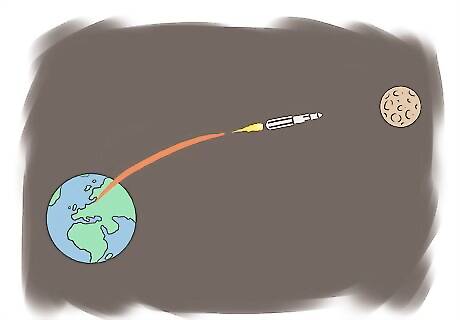

- To get to the moon, first you need to escape Earth's gravity by traveling fast enough in a rocket (25,000 miles per hour, to be specific).

- Once you're orbiting Earth, it's time to fire the thrusters to change your trajectory and head to the moon.

- After entering the moon's orbit, you're ready to descend to the moon's surface and land the spacecraft.

Planning the Trip

Plan to go in stages. Despite the all-in-one rocket ships popular in science fiction stories, going to the moon is a mission best broken into separate parts: achieving low-Earth orbit, transferring from Earth to lunar orbit, landing on the moon, and reversing the steps to return to Earth. Some science fiction stories that depicted a more realistic approach to going to the moon had astronauts going to an orbiting space station where smaller rockets were docked that would take them to the moon and back to the station. Because the United States was in competition with the Soviet Union, this approach was not adopted; the space stations Skylab, Salyut, and the International Space Station were all put up after Project Apollo had ended. The Apollo project used the three-stage Saturn V rocket. The bottom-most first stage lifted the assembly off the launching pad to a height of 42 miles (68 km), the second stage boosted it almost to low Earth orbit, and the third stage pushed it into orbit and then toward the moon. The Constellation project proposed by NASA for a return to the moon in 2018 consists of a two different two-stage rockets. There are two different first stage rocket designs: a crew-only lifting stage consisting of a single five-segment rocket booster, the Ares I, and a crew-and-cargo lifting stage consisting of five rocket engines beneath an external fuel tank supplemented by two five-segment solid rocket boosters, the Ares V. The second stage for both versions uses a single-liquid fuel engine. The heavy lifting assembly would carry the lunar orbital capsule and lander, which the astronauts would transfer to when the two rocket systems dock.

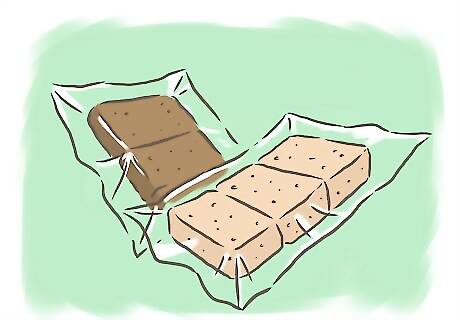

Pack for the trip. Because the moon has no atmosphere, you have to bring your own oxygen so you have something to breathe while you’re there, and when you stroll about on the lunar surface you need to be in a spacesuit to protect yourself from the blazing heat of the two-week-long lunar day or the mind-numbing cold of the equally long lunar night – not to mention the radiation and micro-meteoroids the lack of atmosphere exposes the surface to. You’ll also need to have something to eat. Most of the foods used by the astronauts in space missions have to be freeze-dried and concentrated to reduce their weight and then be reconstituted by adding water when eaten. They also need to be high-protein foods to minimize the amount of body waste generated after eating. (At least you can wash them down with Tang.) Everything you take into space with you adds weight, which increases the amount of fuel necessary to lift it and the rocket carrying it into space, so you won’t be able to take too many personal effects into space – and those lunar rocks will weigh 6 times as much on Earth as they do on the moon.

Determine the launch window. A launch window is the time range for launching the rocket from Earth to be able to land in the desired area of the moon during a time when there would be sufficient light for exploring the landing area. The launch window was actually defined two ways, as a monthly window and a daily window. The monthly launch window takes advantage of where the planned landing area is with respect to the Earth and the sun. Because Earth’s gravity forces the moon to keep the same side facing Earth, exploration missions were chosen in areas of the Earth-facing side to make radio communication between Earth and the moon possible. The time also had to be chosen at a time when the sun was shining on the landing area. The daily launch window takes advantage of launch conditions, such as the angle at which the spacecraft would be launched, the performance of booster rockets, and the presence of a ship downsite from the launch to track the rocket’s flight progress. Early on, light conditions for launching were important, as daylight made it easier to oversee aborts on the launch pad or before achieving orbit, as well as being able to document aborts with photographs. As NASA gained more practice in overseeing missions, daylight launches were less necessary; Apollo 17 was launched at night.

To The Moon or Bust

Lift off. Ideally, a rocket bound for the moon should be launched vertically to take advantage of Earth’s rotation in helping it achieve orbital velocity. However, in Project Apollo, NASA allowed for a possible range of 18 degrees either direction from vertical without significantly compromising the launch.

Achieve low Earth orbit. In escaping the pull of Earth’s gravity, there are two velocities to consider: escape velocity and orbital velocity. Escape velocity is the velocity needed to escape a planet’s gravity completely, while orbital velocity is the velocity needed to go into orbit around a planet. Escape velocity for Earth’s surface is about 25,000 mph or 7 miles per second (40,248 km/hr or 11.2 km/s), while orbital velocity at the surface is . Orbital velocity for Earth’s surface is only around 18,000 mph (7.9 km/s); it takes less energy to achieve orbital velocity than escape velocity. Furthermore, the values for orbital and escape velocity drop the further away from Earth’s surface you go, with escape velocity always about 1.414 (the square root of 2) times orbital velocity.

Transition to a trans-lunar trajectory. After achieving low Earth orbit and verifying that all ship’s systems are functional, it’s then time to fire the thrusters and go to the moon. With Project Apollo, this was done by firing the third-stage thrusters one last time to propel the spacecraft toward the moon. Along the way, the command/service module (CSM) separated from the third stage, turned around, and docked with the lunar excursion module (LEM) carried in the upper part of the third stage. With Project Constellation, the plan is to have the rocket carrying the crew and its command capsule dock in low Earth orbit with the departure stage and lunar lander brought up by the cargo rocket. The departure stage would then fire its thrusters and send the spacecraft to the moon.

Achieve lunar orbit. Once the spacecraft enters the gravity of the moon, fire the thrusters to slow it down and place it in orbit around the moon.

Transfer to the lunar lander. Both Project Apollo and Project Constellation feature separate orbital and landing modules. The Apollo command module required that one of the three astronauts remain behind to pilot it, while the other two boarded the lunar module. Project Constellation’s orbital capsule is designed to be run automatically, so that all four of the astronauts it is designed to carry could board its lunar lander, if desired.

Descend to the moon’s surface. Because the moon has no atmosphere, it is necessary to use rockets to slow the lunar lander’s descent to about 100 mph (160 km/hr) to ensure an intact landing and slower still to guarantee its passengers a soft landing. Ideally, the planned landing surface should be free of sizable boulders; this is why the Sea of Tranquility was chosen as the landing site for Apollo 11.

Explore. Once you land on the moon, it’s time to take that one small step and explore the lunar surface. While there, you can gather lunar rocks and dust for analysis on Earth, and if you brought along a collapsible lunar rover as the Apollo 15, 16, and 17 missions did, you can even hot-rod on the lunar surface at up to 11.2 mph (18 km/hr). (Don’t bother to rev the engine, though; the unit is battery powered, and there’s no air to carry the sound of a revving engine, anyway.)

Returning to Earth

Pack up and go home. After you’ve done your business on the moon, pack up your samples and tools and board your lunar lander for the return trip. The Apollo lunar module was designed in two stages: a descent stage to get it down to the moon and an ascent stage to lift the astronauts back into lunar orbit. The descent stage was left behind on the moon (and so also was the lunar rover).

Dock with the orbiting vessel. The Apollo command module and the Constellation orbital capsule are both designed to take astronauts from the moon back to Earth. The contents of the lunar landers are transferred to the orbiters, and the lunar landers are then un-docked, to eventually crash back to the moon.

Head back to Earth. The main thruster on the Apollo and Constellation service modules is fired to escape the moon’s gravity, and the spacecraft is directed back to Earth. On entering Earth’s gravity, the service module thruster is pointed toward Earth and fired again to slow the command capsule down before being jettisoned.

Go for a landing. The command module/capsule’s heat shield is exposed to protect the astronauts from the heat of re-entry. As the vessel enters the thicker part of Earth’s atmosphere, parachutes are deployed to slow the capsule further. For Project Apollo, the command module splashed down in the ocean, as previous manned NASA missions had done, and was recovered by a Navy vessel. The command modules were not re-used. For Project Constellation, the plan is to touch down on land, as Soviet manned space missions did, with splashdown in the ocean an option if touchdown on land is not possible. The command capsule is designed to be refurbished, replacing its heat shield with a new one, and reused.

Comments

0 comment