views

X

Trustworthy Source

Cleveland Clinic

Educational website from one of the world's leading hospitals

Go to source

Medical professionals are trained to use stethoscopes, but you can learn how to use one too. Keep reading to learn how to use a stethoscope.

Choosing and Adjusting a Stethoscope

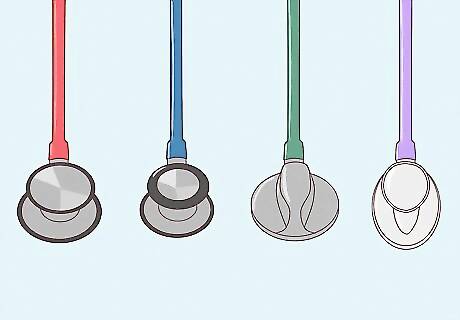

Get a high-quality stethoscope. A high-quality stethoscope is important. The better the quality of your stethoscope, the easier it will be for you to listen to your patient’s body. Single tubed stethoscopes are better than double tubed ones. The tubes in double tubed stethoscopes can rub together. This noise can make it hard to hear heart sounds. Thick, short, and relatively stiff tubing is best, unless you plan to wear the stethoscope around your neck. In that case, a longer tube is best. Make sure that tubing is free of leaks by tapping on the diaphragm (the flat side of the chest piece). As you tap, use the earpieces to listen for sounds. If you don’t hear anything, there may be a leak.

Adjust your stethoscope’s earpieces. It is important to make sure that the earpieces are facing forward and that they fit well. Otherwise, you might not be able to hear anything with your stethoscope. Make sure that the earpieces are facing forward. If you put them in backwards, you won’t be able to hear anything. Make sure that the earpieces fit snugly and have a good seal to keep out ambient noise. If the ear pieces don’t fit well, most stethoscopes have removable earpieces. Visit a medical supply store to purchase different earpieces. With some stethoscopes, you can also tilt the earpieces forward stethoscopes to ensure a better fit.

Check the earpiece tension on your stethoscope. Make sure that the earpieces are close to your head but not so close that they’re uncomfortable. If your earpieces are too tight or too loose, readjust them. If the earpieces are too loose, you won’t be able to hear anything. To tighten the tension, squeeze the headset near the earpieces. If the earpieces are too tight, they might hurt your ears and you’ll have a hard time using your stethoscope. To reduce the tension, pull the headset apart gently.

Choose an appropriate chest piece for your stethoscope. There are many different types of chest pieces available for stethoscopes. Choose one that is appropriate for your needs. Chest pieces come in different sizes for adults and children. The chest piece is also known as the diaphragm and bell. Different chest pieces have different acoustic levels based on whether you’re using them on adults, children, or people with cardiovascular issues.

Preparing to Use a Stethoscope

Select a quiet place to use your stethoscope. You won’t be able to accurately take readings if there’s a lot of background noise. Find a quiet area to ensure that the body sounds you want to hear will not be overpowered by background noises.

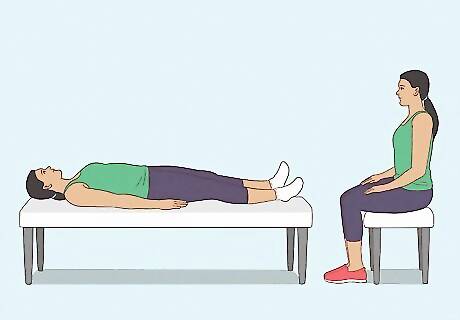

Position your patient. To listen to the heart and abdomen, ask your patient to get into a supine position. To listen to the lungs, ask your patient to sit upright. Heart, lung, and bowel sounds may sound different depending on the patient's posture (sitting, standing, lying on one's side, etc.), so you may want to take multiple readings from different positions.

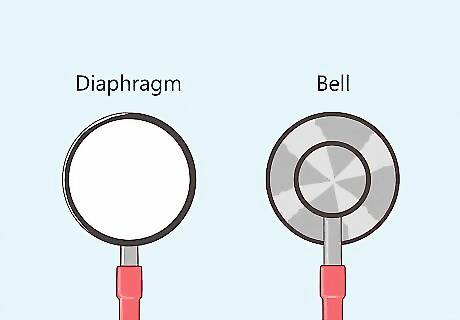

Decide whether to use the diaphragm or bell. The diaphragm, which is the flat side of the drum, is better for hearing medium- and high-pitched sounds. The bell, which is the round side of the drum, is better for hearing low-pitched sounds. If you want a stethoscope with really high sound quality, consider an electronic stethoscope. These models provide amplification so that it is easier to hear heart and lung sounds, although they can be a little more expensive.

Place the stethoscope directly on the patient’s skin. Use the stethoscope on bare skin to avoid picking up the sound of rustling fabric. If your patient has a lot of chest or back hair, keep the stethoscope still to avoid any interfering sounds. To make your patient more comfortable, warm up the stethoscope by rubbing it on your sleeve, or consider buying a stethoscope warmer.

Listening to the Heart

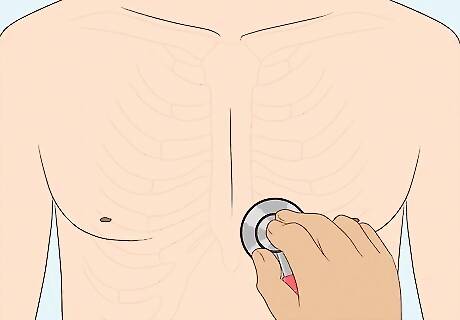

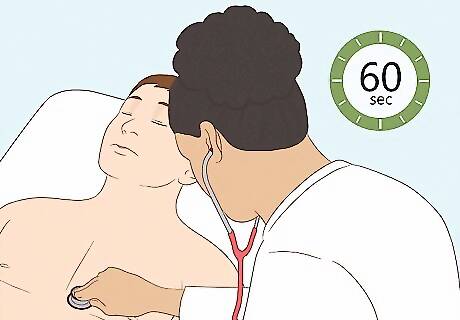

Hold the diaphragm over the patient’s heart. Position the diaphragm on the left side of the patient’s upper chest where the 4th to 6th ribs meet (almost directly under the breast). Hold the stethoscope between your pointer and middle fingers and apply enough gentle pressure so that you don’t hear your fingers rubbing together.

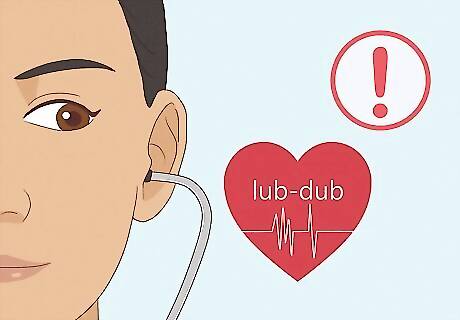

Listen to the heart for a full 60 seconds. Ask the patient to relax and breathe normally. You should hear the normal sounds of the human heart, which resemble a “lub-dub” sound. The individual sounds in this two-tone pattern are known as the systolic and diastolic. Systolic is the “lub” sound and diastolic is the “dub” sound. The “lub,” or systolic, sound happens when the mitral and tricuspid valves of the heart close. The “dub,” or diastolic, sound happens when the aortic and pulmonic valves close.

Count the number of heartbeats you hear in a minute. The normal resting heart rate for adults and children over 10 years old is between 60-100 beats per minute (bpm). For well-trained athletes, the normal resting heart rate may only be between 40-60 bpm. There are several different ranges of resting heart rates to consider for patients under 10 years of age. Those ranges include: Newborns up to one-month-old: 70-190 bpm Infants 1-11 months: 80-160 bpm Children 1-2 years: 80-130 bpm Children 3-4 years: 80-120 bpm Children 5-6 years: 75-115 bpm Children 7-9 years: 70-110 bpm

Listen for abnormal heart sounds. As you count the heartbeats, listen for any abnormal sounds. Anything that does not sound like that “lub-dub” may be considered abnormal. If you hear anything abnormal, your patient requires a further evaluation by a doctor. If you hear a whooshing sound or a sound that is more like “lub...shhh...dub,” your patient may have a heart murmur. A heart murmur is caused by blood rushing quickly through the valves. Many people have what are called “innocent” heart murmurs. However, some murmurs point to issues with the heart valves, so you advise your patient to see a doctor if you detect a heart murmur. If you hear a third sound that resembles a low-frequency vibration, your patient might have a ventricular defect. This third heart sound is referred to as S3 or a ventricular gallop. Advise the patient to see a doctor if you hear a third heart sound. Try listening to samples of normal and abnormal heart sounds to help you determine if what you are hearing is normal.

Listening to the Lungs

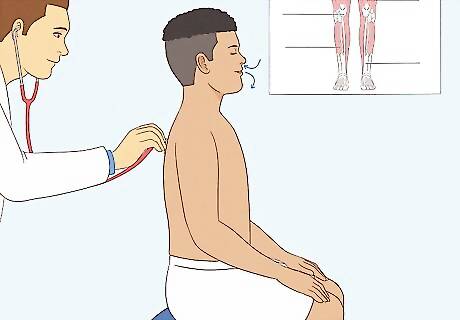

Ask your patient to sit straight up and breathe normally. Put the stethoscope on the patient’s back, behind one of the lungs. As you listen, you can ask the patient to take a deep breath if you cannot hear breath sounds or if they are too quiet to determine if there are any abnormalities.

Use the diaphragm of your stethoscope to listen to your patient’s lungs. As you listen to the patient’s lungs, move the stethoscope to the upper and lower lobes. Move from the back to the front of the patient’s chest. Rotate as many times as you need between the upper part of the chest, the midclavicular line of the chest, and the bottom part of the chest. Make sure to listen to the front and back of all of these regions. Make sure to compare both sides of your patient’s lungs and note if anything is different between the left and right lungs. By covering all of these positions you will be able to listen to all of the lobes in your patient’s lungs.

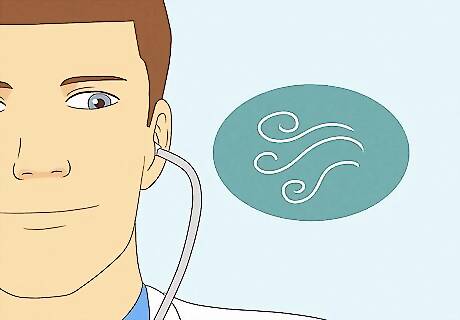

Listen for normal breath sounds. Normal breath sounds are clear and consistent, like listening to someone blowing air into a large bottle. Listen to a sample of healthy lungs and then compare the sounds to what you hear in your patient’s lungs. There are two types of normal breath sounds: Bronchial breath sounds are those heard within the tracheobronchial tree. Vesicular breath sounds are those heard over the lung tissue.

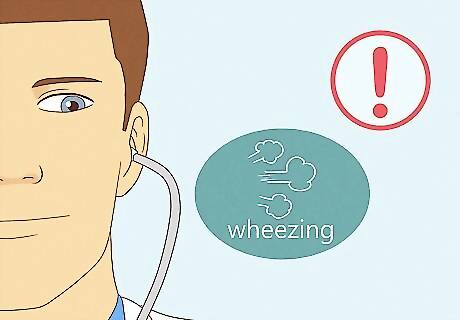

Listen for abnormal noise in your patient’s breathing. Abnormal breath sounds include wheezing, stridor, rhonchi, or rales. If you do not hear any strange sounds, the patient may have air/fluid around the lungs, thickness in the chest wall, a throttled airflow, or over-inflation in the lungs. There are four types of abnormal breath sounds: Wheezing sounds like a high-pitched sound when the person exhales, and sometimes when they inhale as well. Many patients who have asthma also have wheezes. Stridor sounds like high-pitched musical breathing. It’s similar to wheezing, and heard most often when the patient inhales. Stridor is caused by a blockage in the back of the throat. Rhonchi sounds like snoring. Rhonchi cannot be heard without a stethoscope and happens because the air is following a “rough” path through the lungs (usually because the path is blocked). Rales sounds like popping bubble wrap or rattling in the lungs. Rales can be heard when a person inhales.

Listening to Abdominal Sounds

Place the diaphragm on your patient’s bare stomach. Use your patient’s belly button as the center and divide your listening around the belly button into four sections. Listen to the upper left, upper right, lower left, and lower right.

Listen for normal bowel sounds. Normal bowel sounds typically resemble stomach growls or grumbles. Anything else may suggest that something is wrong and that the patient requires further evaluation. You should hear “growling” in all four sections. Sometimes after surgery, bowel sounds will take a while to return.

Pay attention and listen for abnormal bowel sounds. Most of the sounds that you hear when listening to your patient’s bowels are just the sounds of digestion. Although most bowel sounds are normal, some abnormalities could point to a problem. If you are unsure if the bowel sounds you hear are normal and/or the patient has other symptoms, tell the patient to see a doctor for further evaluation. If you do not hear any bowel sounds, that may mean that something is blocked in the patient’s stomach. It can also indicate constipation. If the bowel sounds don’t return over time, there may be a blockage. In this case, the patient needs further evaluation by a doctor. If the patient has hyperactive bowel sounds followed by a lack of bowel sounds, that could indicate that there has been a rupture or necrosis of the bowel tissue. If the patient has very high-pitched bowel sounds, this may indicate that there is an obstruction in the patient’s bowels. Slow bowel sounds may be caused by prescription drugs, spinal anesthesia, infection, trauma, abdominal surgery, or overexpansion of the bowel. Fast or hyperactive bowel sounds can be caused by Crohn’s disease, a gastrointestinal bleed, food allergies, diarrhea, infection, and ulcerative colitis.

Listening For a Bruit

Determine if you need to check for a bruit. If you have detected a sound that seems like a heart murmur, you should also check for a bruit. Since heart murmurs and bruits sound similar, it is important to check for both if one is suspected.

Place the diaphragm of your stethoscope over one of the carotid arteries. The carotid arteries are located in the front of your patient’s neck, on either side of the Adam’s apple. If you take your index and middle finger and run them down the front of your throat, you will trace over the locations of your two carotid arteries. Be careful not to press too hard on the artery or you may cut off circulation and cause your patient to faint. Never press on both carotid arteries at the same time.

Listen for any bruits. A bruit makes a whooshing sound that indicates that an artery is narrowed. Sometimes, a bruit may be confused with a murmur because they sound so similar. However, a bruit’s whooshing sound will be much louder than a traditional murmur when you listen to the carotid artery specifically. You may also want to listen for bruits over the abdominal aorta, renal arteries, iliac arteries, and femoral arteries.

Checking Blood Pressure

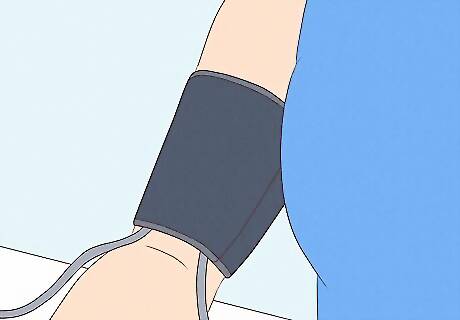

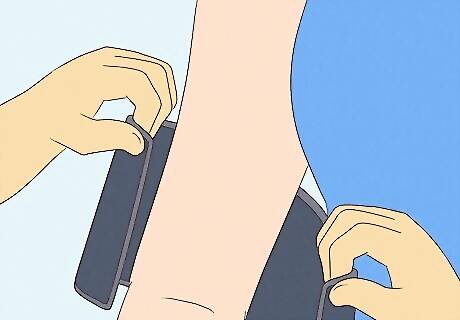

Wrap the blood pressure cuff around your patient’s arm, right above the elbow. Roll up your patient’s sleeve if it is in the way. Make sure that you use a blood pressure cuff that fits your patient’s arm. You should be able to wrap the cuff around your patient’s arm so that it is snug, but not so tight that the patient is in pain. If the blood pressure cuff is too small or too large, get a different size.

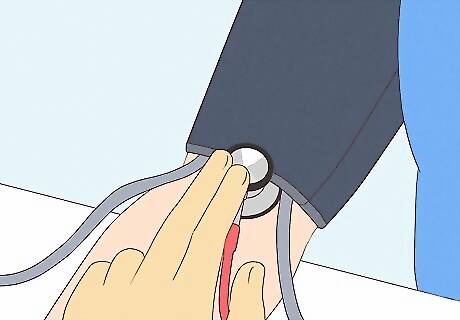

Press the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the brachial artery. Set the stethoscope just below the cuff's edge. You can also use the bell if you have trouble hearing with the diaphragm. You will be listening for Korotkoff sounds, which are low-tone knocking/thumping sounds. This is the patient’s systolic blood pressure. If you’re having trouble, try doing this on your own body. Find your pulse in your inner arm to help you determine where your brachial artery is located.

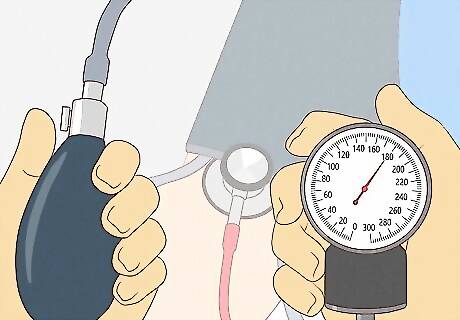

Inflate the cuff to 180 mm Hg, or 30 mm above your expected systolic pressure. You can find the reading by looking at the sphygmomanometer, which is the gauge on the blood pressure cuff. Once you reach 180 mm HG (or 30 mm above the expected rate), release air from the cuff at a moderate rate (around 3 mm/sec). As you release the air, listen with the stethoscope and keep your eyes on the sphygmomanometer.

Listen for Korotkoff sounds to find the diastolic pressure. The first knocking sound that you hear is your patient’s systolic blood pressure. Note that number, but keep watching the sphygmomanometer. After the first sound stops, note the number that it stops on. That number is the diastolic pressure.

Release the pressure entirely and remove the cuff. Deflate the cuff entirely and take it off of your patient after you’ve gotten the second number. You now have two numbers that make up your patient’s total blood pressure. Record these numbers side by side, separated by a slash. For example, 110/70.

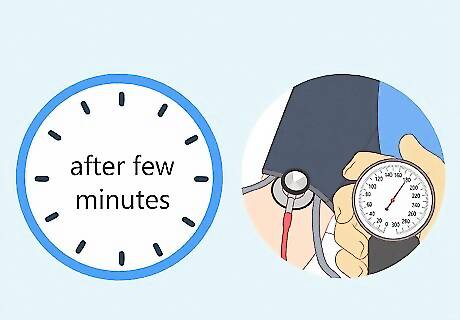

Wait a few minutes if you want to check the patient’s blood pressure again. You may want to re-measure if the patient’s blood pressure is high. This is especially a good idea if the patient seems stressed or they’re not used to getting their blood pressure taken. A systolic blood pressure above 120 or a diastolic blood pressure above 80 indicates that your patient may have high blood pressure. In that case, your patient should seek further evaluation by a doctor.

Comments

0 comment