views

Researching Your Dialogue

Pay attention to actual conversations. Listen to the way people talk to one another and use those conversations and patterns in your dialogue to make it sound authentic. You'll notice that people talk differently when they're with different people, so make sure that you include that when you're writing dialogue. Disregard parts of the conversation that will not translate well when written down. For example, every "hello" and "goodbye" does not need to be written. Some of your dialogue might start with a "Did you do 'this'?" or "Why did you do 'this'?" Keep a notebook to record small pieces of real-world dialogue that stand out to you.

Read good dialogue. To get a good feel for the balance that you need in your dialogue between realistic speech and book speech you need to read good dialogue in books and in movies. Look at books and scripts and see what works and what doesn't and try to figure out why. Look for writers whose dialogue rings true to your ear, regardless of what other readers or critics may say. If you need a starting point, you might check out the work of Douglas Adams, Toni Morrison, and Judy Blume, who are known for their realistic, layered, and vivid dialogue. Checking out and practicing writing dialogue for screenplays and radio plays is really useful in developing dialogue, since those are both very dependent on dialogue. Douglas Adams, from the above writers, got his start writing radio plays, which is one reason for his fantastic dialogue.

Develop your characters fully. You will need to completely understand your characters before you can make them talk. You'll need to know things like whether they're taciturn and monosyllabic, or whether they love to use lots of big words to impress people, and so on. You don't need to write every character detail into your work, but you should know them yourself. Things like age, gender, education level, region where they're from, tone of voice, will all make a difference in how a character talks. For example, a poor American teen girl is going to talk very differently from a rich, old, British guy. Give each character a distinct voice. Not all of your characters are going to use the same vocabulary, tone or method of speech. Make sure each character sounds different.

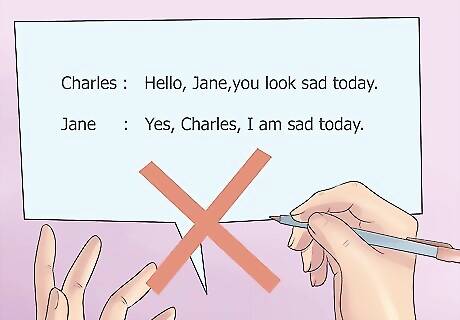

Learn to avoid stilted dialogue. Stilted dialogue might not completely kill a story, but it can definitely jerk a reader out of the story, which as a writer, is something you're trying not to do. Occasionally stilted dialogue does work, but only with the most specific kind of story. Stilted dialogue is dialogue that only works on the obvious levels and in language no one would use. For example: "Hello, Jane, you look sad today," said Charles. "Yes, Charles, I am sad today. Would you like to know why?" "Yes, Jane, I would like to know why you are sad today." "I am sad because my dog is sick and it reminds me of the death of my father two years ago under mysterious circumstances." How the dialogue above should have gone: "Jane, is something wrong?" asked Charles. Jane shrugged, keeping her gaze fixed on something out the window. "My dog's sick. They don't know what's wrong." "That's terrible, but, Jane...well, he is old. Maybe that's all it is." Her hands clenched on the windowsill. "It's just, it's just, you'd think the doctors would know." "You mean the vet?" Charles frowned. "Yeah. Whatever." The reason the second one works better, is that it doesn't come right out and say that Jane is thinking of her deceased father, but it does lean towards that interpretation, especially with her using the word "doctors" instead of "vet." It also flows better. An example where stilted dialogue works is Lord of the Rings, where the characters' conversations can get very grand and eloquent (and unrealistic). This is a good choice for a book that's written in the style of old epics, like Beowulf or The Mabinogion.

Writing Out Dialogue

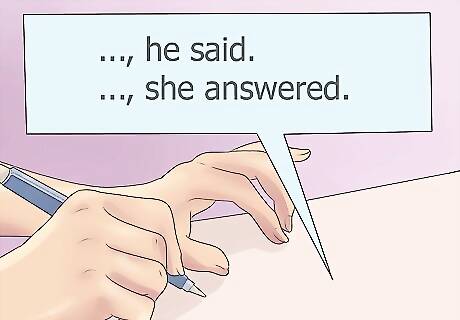

Match your dialogue verbs to the tone of your story. Some stories might work best with simple dialogue descriptors like "said" or "answered." Others might sound great with more descriptive words, like "protested" or "exclaimed." Your story might even work with a mix of the two! Go with whatever sounds best to you in the context of your work. No matter what you choose, make sure you don't use the same descriptor over and over. This gets repetitive and boring for the reader.

Move the story forward with your dialogue. It should provide information to the reader about the story or the characters. Dialogue is a great way to prove character development or character information that your reader might not otherwise get. Don't do small talk about the weather or how each character is doing, even if that's something that comes up a lot in real conversations. Now, a way in which small talk would be well used is to build up tension. For example, a character really needs certain information from another character, but the second character insists upon the ritual of small talk, your reader and your character will be biting their nails in waiting to get to the good stuff. All your dialogue should have a purpose. As you're writing dialogue, ask yourself, "what does this add to the story?" "What am I trying to tell the reader about the character or the story?" If you don't have an answer to those questions, scrap the dialogue.

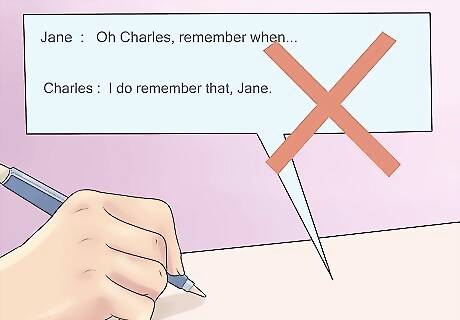

Don't info dump in your dialogue. This is a big one that a lot of people have the tendency to do. You think, what better way to get information across to my reader than by having my characters discuss it at length? Hold it right there! Background information needs to be added sporadically throughout the story. For example of what not to do: Jane turned to Charles and said, "Oh Charles, remember when my father died a mysterious death and my family was turned out of our home by my evil aunt Agatha?" "I do remember that, Jane. You were only 12-years-old and you had to drop out of school to help out your family." A better version of the above might go something like: Jane turned to Charles, her lips set in a grim line. "I heard from aunt Agatha today." Charles was taken aback. "But she was the one that kicked your family out of your house. What did she want?" "Who knows, but she started hinting things about my dad's death." "Things?" Charles raised an eyebrow. "She seemed to think his death wasn't natural."

Add subtext. Conversations, especially in stories, are layered affairs. There's usually more than one thing going on in them, so you want to make sure that you capture the subtext of each situation. There are lots of ways to say things. So, if you have a character that you want to say something like "I need you," try having them say as much, without actually saying it. For example: Charles started for his car. Jane placed a hand on his arm; she was chewing at her lip. "Charles, I...do you really have to go so soon?" she asked, withdrawing her hand. "We still haven't figured out what we're going to do." Don't have your characters say everything they're feeling or thinking. That will give away too much and won't allow for any suspense, or nuance.

Mix it up. You want your dialogue to be interesting and to keep your reader engaged in the story. This means skimming over background conversations, like people at the bus stop discussing the weather, and getting into the meaty conversations, like Jane's confrontation with treacherous Aunt Agatha. Engage your characters in arguments or have them say surprising things, as long as these things are in character for them. Dialogue should be interesting. If everyone is agreeing or asking and answering basic questions, the dialogue will get boring. Intersperse your dialogue with action. When people are having conversations they fiddle with things, laugh, wash the dishes, trip over things, and so on. Adding these things to the dialogue will make it come alive. For example: "You don't think a healthy specimen like your daddy would've just sickened and died," Aunt Agatha said with a cackle. Jane clung to the shreds of her temper, replying "Sometimes people get sick." "And sometimes they get a little help from their friends." Aunt Agatha sounded so smug Jane wanted to reach through the phone and wring her neck. "if someone killed him, Aunt Agatha, do you know who?" "Oh, I've got a few notions, but I'll let you decide on your own."

Proofreading Dialogue

Read your dialogue out loud. This will give you an opportunity to hear how it sounds. You can make changes based on what you hear as well as what you read. Allow a little time to go by after you've written the dialogue to read it, otherwise your brain will fill in what you were going for rather than what is actually on the page. Have a trusted friend or family member go over your dialogue. A fresh pair of eyes can tell you whether your dialogue is natural sounding, or needs work.

Punctuate your speech correctly. There is nothing more irritating to a reader (including and especially, publishers and agents) than punctuation that is being abused, especially in dialogue. There should be a comma after the end of the dialogue and the closing quotation mark. For example: "Hello. I'm Jane," said Jane. If you add action to the middle of a piece of dialogue, you'll either capitalize the second half of the dialogue, or not. For example: "I can't believe he killed my father," Jane said, her eyes filling with tears. "It's just not like him." or "I can't believe he killed my father," Jane said, her eyes filling with tears, "since it's just not like him." If there's no said, only an action, then there's a period in place of a comma in the closing quotation mark. For example: "Goodbye, Aunt Agatha." Jane slammed the phone down.

Cut out any unnecessary words or phrases. Sometimes, less dialogue is more. When people talk, they are not overly verbose. They say things in short, simple ways and you'll want to reflect that in your dialogue. For example, instead of "I cannot believe that after all these many years, it was Uncle Red that put the poison in my father's evening cocktail and murdered him," said Jane, you might say "I can't believe Uncle Red poisoned my father!"

Use dialect carefully. Each character should have her own sound and voice, but too much of an accent or a drawl will become annoying or even offensive to readers. Also, using a dialect you aren't familiar with can end up employing stereotypes and being incredibly offensive to the natural speakers of the dialect. Establish where characters come from in other ways. For example, use regional terms such as "soda" versus "pop" to establish geography. Make sure if you're writing a character from a specific geographic area (like England or America) that you use the appropriate slang and terminology (pants in England, underwear in America, for example).

Comments

0 comment