views

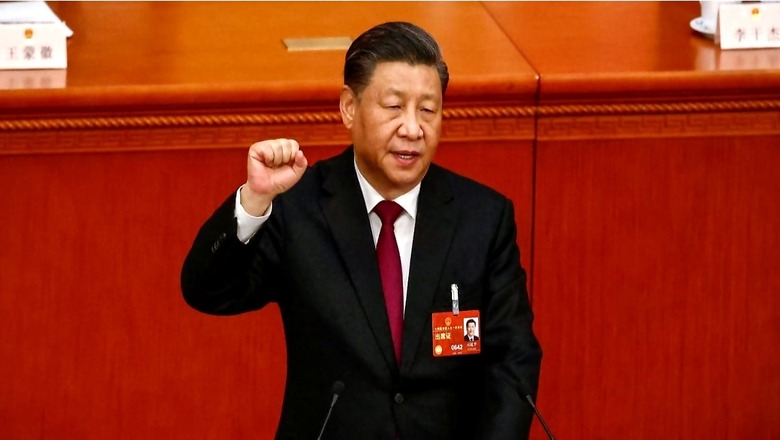

By giving Chinese and Tibetan names to eleven sites in Arunachal Pradesh which it calls South Tibet, China is being knowingly provocative. It is assuming that India will fret and fume but will not take retaliatory action on issues that are of equal sensitivity to China. This is the third time that China has similarly renamed places in Arunachal Pradesh, the first time in 2017 and the second in 2021. India has protested in each case without seeking to escalate matters by targeting China on territorial issues.

Calling Arunachal Pradesh South Tibet was a major provocation by China which India swallowed. By giving Chinese and Tibetan “standardised” names to several places in Arunachal Pradesh China seeks to consolidate its territorial claim on the Indian state, both internally and externally, dilute the Indian personality of the state and create an artificial historical basis for its claim by affirming its longstanding Tibetan- and by extension- Chinese past. This is laying the basis of One-Tibet policy, as it were.

This latest affront comes when the two countries are locked into a military confrontation in Ladakh for three winters now followed by violent incidents in the eastern sector. Several rounds of discussions have taken place at the military and diplomatic level to reduce tensions, but issues arising from China’s violation of existing bilateral border agreements remain fundamentally unresolved. External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar has repeatedly highlighted the dangerous potential of the situation in Ladakh, stressing that the overall relations between the two countries cannot become normal if the situation on the border remains abnormal. He has underscored the breakdown of trust between the two countries.

China clearly does not give much weight to these Indian admonitions. Beijing is obviously not bothered about earning India’s “trust”, though what Jaishankar really means is that India expected China to strictly adhere to border agreements aimed at preventing differences from erupting into armed conflict, and it is this shared understanding that has been unilaterally breached by China. India, therefore, can no longer “trust” China to adhere to negotiated agreements.

China no doubt understands that its latest provocation will stoke more “mistrust” on the Indian side, but its view would be that relations between countries are not based on “trust” but on power balances, and therefore India’s argument about “trust” is merely a “moral” one which cannot be the basis of long term ties even between friendly countries when their national interests can evolve and come into conflict. China is, in any case, highly self-centred and self-seeking, and relies currently on its rising comprehensive national power to achieve its hegemonic goals with the financial and economic tools at its command.

The surprising part of China’s latest provocation is its timing when the G20 meetings are on under India’s presidency. Why draw attention to China’s territorial expansionism when India is hosting a series of meetings of the leading economies of the world and security issues have become an integral part of these discussions? Why when China’s threats to Taiwan are causing international concern? Why also when the SCO and G20 summits will be held later in the year which President Xi Jinping is expected to attend. Instead of creating a congenial atmosphere before these summits, China is injecting more tensions into ties with India, which makes any productive outcome of any potential summit contact between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi even less likely.

Beyond the bilateral India-China equation, China seems unconcerned about how its provocations against India conflict with Russia’s push, with Chinese support, for multipolarity, originally the strategic purpose of the Russia-China-India (RIC) dialogue, later expanded to BRIC with Brazil’s inclusion and BRICS with South Africa’s membership. The RIC format of promoting multipolarity can hardly be advanced with China expanding its differences with India and seeking, in India’s view, unipolarity in Asia.

BRICS also cannot achieve its objectives of a more democratic world order, less dominated by the West, with modes of political, economic and financial cooperation that cater best to the interests of its members if India and China have mounting bilateral differences. BRICS and SCO are supposed to showcase a different mode of conducting relations between countries based on equality, respect for each other’s concerns, non-interference in the internal affairs of countries, dialogue and peaceful resolution of differences, etc. China is breaching these principles in its relations with India, which complicates President Vladimir Putin’s reinvigorated push for multipolarity as a counter to the collapse of its ties with the US and Europe.

If the Chinese let it be known through their own commentators, as well as some analysts in India, that our growing closeness to the US, our membership of Quad and so on, are the cause of China’s military and political moves against India, the question arises how the latter will not actually create more consensus in India about stronger India-US ties within a larger Indo-Pacific strategy to counter the China threat, and with Japan and Australia as well. Concerns in the US and now in the EU too about China’s threat to Taiwan have led to calls for an Indo-Pacific role for NATO. China’s aggression towards India contributes indirectly to the need felt by the West to strategically deter Beijing.

The participation of Japan and South Korea in the Madrid NATO summit in 2022 can be seen as supportive of NATO’s geographic creep. China has to weigh whether in this context it is in its interest to reach out to India rather than alienating it further. It is possible that China’s latest move could be a riposte to the resolution moved in the US Congress to recognise Arunachal Pradesh as an integral part of India and the holding of a G20 meeting in Itanagar. But these would be excuses to justify the underlying assertive and aggressive policies of China under President Xi. As it happens, the White House spokesperson has slammed China’s move to rename localities in Arunachal Pradesh, stating that the US has long recognized Arunachal Pradesh as Indian territory.

India seems unwilling to retort concretely to China’s provocations. The MEA spokesperson’s statement on the latest provocation is a virtual repeat of what the Ministry said in 2021, which is surprising. Even if we want to avoid hard steps at this stage for various considerations, a more robust response could have been made. To say Arunachal Pradesh is and always will remain an inalienable part of India is essentially a defensive statement. China could have been asked to stop making meaningless paper exercises, cease harbouring illusions about its power and capacity to wrest India’s territory by force, act more responsibly internationally and not engage in double standards by threatening the use of force in its neighbourhood and advocate peaceful solutions to issues elsewhere. We should caution against China’s irredentism in Tibet being used for territorial aggrandisement vis a vis India, pointing out that while it suppresses the rights of Tibetans internally, it seeks to cynically expand Tibetan “rights” externally in India.

We must reflect on pursuing some other options depending on developments. The Chinese Foreign Ministry has already rejected India’s latest protest and reiterated its sovereignty over “Zagnan”, the name it gives to South Tibet. While we have accepted Tibet as part of China, it was an autonomous Tibet, not a militarised one. Tibet not only has no autonomy, but it has also become a base for China to threaten India’s security and claim large tracts of our territory. This changes the essential basis of our 1954 recognition. We should begin to show in our maps India bordering Tibet and not China, and the depiction of territory of Tibet in dotted lines should be that of Greater Tibet and not the truncated Tibet Autonomous Region. Our media should also depict our northern boundary similarly in its reporting on India-China border issues.

We need not also follow the Sincised name of East Turkestan as Xinjiang. If China can Sinicise names in Arunachal Pradesh, we can de-Sinicise East Turkestan’s Chinese name.

Kanwal Sibal is a former Indian Foreign Secretary. He was India’s Ambassador to Turkey, Egypt, France and Russia. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment