views

Globally, June 5 is the World Environment Day. It was created to raise awareness and spur actions to protect the environment. This year, emissions from transport are a major focus because the sector is responsible for almost a quarter of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the world. That’s one part of the story. The other part is that the transport sector’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have increased consistently over the year. The transport sector was the second-biggest source behind the energy sector in terms of annual change in CO2 emissions between 2020 and 2021.

In India, too, transport is one of the sectors where emissions are growing fastest, and it accounts for around 14% of CO2 emissions, 90% of them from road transport. Therefore, reducing emissions from road transport is vital for achieving the country’s climate goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2070.

So, the big question is: How can India reduce emissions from road transportation? The International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) has published a life-cycle assessment of GHG emissions for passenger cars and two-wheelers in India that provides some interesting and relevant insights. The objective of this research was to identify the fuel and power train technologies, which can offer deep carbon-reduction benefits. The study included all GHG emissions from vehicle production, maintenance, and recycling phases, and emissions from fuel and electricity production and consumption.

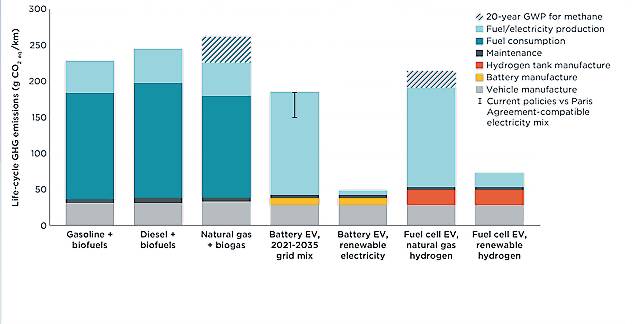

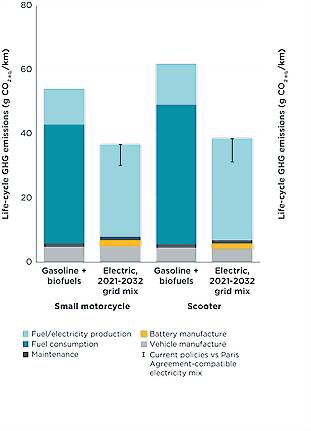

In many ways, the assessment can be considered to have settled the debate over the effective pathways for decarbonizing road transport. Figure 1 illustrates the results for passenger cars and Figure 2 shows emissions for two-wheelers, both in India. Note that the error bars indicate the difference between the development of the electricity mix according to stated policies (the higher values) and what is required to align with the Paris Agreement.

Figure 1. Life-cycle GHG emissions of average new sedan segment gasoline, diesel, and compressed natural gas (CNG) cars, battery electric vehicles (BEVs), and fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEVs) registered in India in 2021.

Figure 2. Life-cycle GHG emissions of average new gasoline combustion engine and battery electric motorcycles and scooters registered in India in 2021.

Let’s discuss three important takeaways from the analysis:

Paris Agreement Goals Can’t Be Achieved with Internal Combustion Engine

Both diesel and natural gas-powered cars exceed the life-cycle GHG emissions of gasoline cars registered in 2021. With a modest share of biofuels in fuel blends (5% to 20% ethanol, and up to 5% biodiesel), the GHG reduction benefits are minimal. While higher biofuel blends could further reduce GHG emissions, the supply of waste- and reside-based biofuel feedstock is highly constrained and is not likely to be enough to substantially displace fossil fuel. Food-based biofuels, on the other hand, not only cause additional emissions from indirect land-use change but can also interfere with food security.

The story is the same for trucks. A look at the well-to-wheel (life-cycle) emissions of liquefied natural gas (LNG) trucks shows that they are invariably worse than diesel. This is because methane leakage upstream and downstream offsets any climate benefits offered by natural gas. Different from other GHGs, methane contributes several times more to global warming in the first 20 years after it is emitted than is reflected by the 100-year global warming potential (GWP).

Electric is Cleaner, Even with Existing Grid in India

Even starting with India’s current grid, which gets almost three-fourths of its electricity from fossil fuels, battery-electric vehicles emit less over their lifetimes than internal combustion engine vehicles. Indeed, electric cars registered in 2021 are estimated to produce 19%-34% fewer GHG emissions than gasoline cars. The emissions reduction in the case of electric two-wheelers is even larger, 33%-50% less than gasoline models. Moreover, the benefits will increase over time.

Renewables already contributed almost 11% of the total electricity generated in India in FY 2021–22. With more than 100 GW of installed capacity of renewable energy already today, India is on track to reach 450 GW by 2030. As the grid becomes cleaner, the GHG benefits further increase to 30% in 2030. Notably, the ICCT found that BEVs powered by renewable electricity produce the least emissions, even less than FCEVs powered by green hydrogen. This is because the electricity-based FCEV pathway is three times more energy intensive.

Given the life-cycle GHG emission benefits that BEVs already provide today, the transition to electric cars need not and cannot wait another decade for additional power sector improvements.

Hydrogen is Promising, But Has Limited Application

Fuel cell electric cars emit about 16% fewer life-cycle GHG emissions than gasoline cars when the hydrogen is produced through reforming methane from natural gas, or “grey hydrogen.” The emission reduction benefits are even better when grey hydrogen is combined with carbon capture and storage (CCS) to create “blue hydrogen,” and highest when produced from renewable electricity, the aforementioned “green hydrogen.”

With India’s increasing renewable power portfolio and solar tariffs hitting record low prices, green hydrogen appears promising. However, addressing challenges related to costs and distribution infrastructure will be crucial. It is important to note that the existing CNG infrastructure can be used to transport hydrogen only in small, blended quantities. Thus, the transport of hydrogen would require significant capital investment to create a dedicated pipeline network, and that would be reflected in the at-the-pump price of hydrogen.

With declining solar prices and electrolyzer costs, at-the-pump prices of green hydrogen are expected to go down from USD 9/kg in 2030 to USD 5/kg in 2050. Until then, though, this fuel pathway is likely to be limited to heavy vehicle applications that are located near hydrogen production facilities, as that would not require extensive distribution.

The ICCT research makes clear that there is no realistic pathway to decarbonize the internal combustion engine in a time frame that is compatible with global climate goals. Only BEVs and FCEVs have the potential to achieve near-zero GHG emissions in the coming decades. Thus, as India charts its future and develops sectoral targets for achieving its net-zero goal, it will need to develop strong central policies that support zero-emission vehicles and phase out internal combustion engine vehicles.

Amit Bhatt is Managing Director (India) for the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). Harsimran Kaur is Associate Researcher (Consultant) for ICCT. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment