views

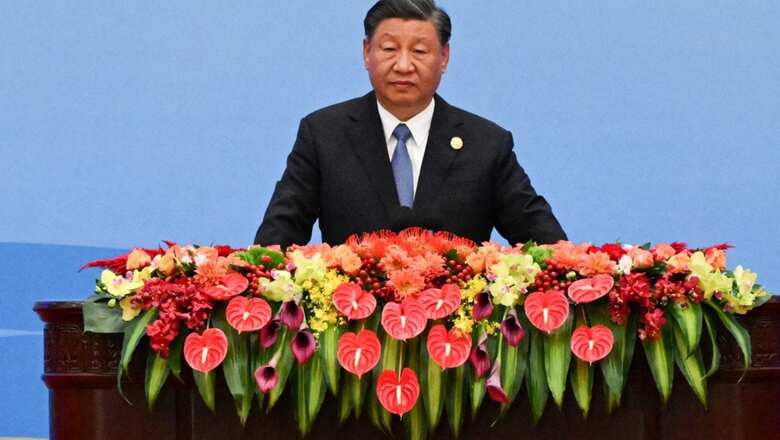

The Global Times never disappoints with its grandiose symphonies of self-praise, serenading the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as if it were a messianic caravan bestowing prosperity upon every corner it graces. In their latest editorial, they wax poetic about the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRF’s) dazzling showcase of “high-quality cooperation” and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s prophetic foresight, all while painting a utopian landscape where every nation is hand-in-hand, skipping down the Silk Road to the tune of mutual success.

They tout “eight major steps” like a magic formula set to conjure universal affluence, all the while side-eyeing those “small yard, high fence” countries that dare question the altruistic spirit of China’s infrastructural bonanza. It’s a narrative where the BRI, in its saintly magnanimity, doesn’t just originate from China, but rather belongs to the world, a gift so precious it’s a wonder it wasn’t delivered on a silk cushion carried by a procession of pandas. Amidst the fanfare, the Global Times assures us that the BRI stands on the “right side of history,” a phrase so overused it’s practically begging for retirement. The editorial ends on a predictably triumphant note, prophesying a “magnificent new epic” in the BRI’s next decade, because, of course, what’s a good piece of propaganda if it doesn’t promise a fairytale ending?

China has been suggesting that the third BRF “opened with grandeur” on October 18, 2023. However, this might not be a correct characterisation. Despite the anticipation for the BRF in four years and its significant ten-year milestone, the event seemed to lack the grandeur of previous editions. With a noticeable dip to just 23 heads of state or government, compared to 37 in 2019, China seemed hesitant to release the list, focusing instead on lower-tier representatives. Perhaps the grand vision of BRF needs recalibration.

The conspicuous absence of European leaders at this year’s BRF starkly highlighted the changing dynamics of China-European relations. In the 2017 edition, European heads of state or government represented a third of all attendees, a number that slightly increased in 2019. However, this year saw a significant drop with only three key figures from Europe: Hungarian PM Viktor Orban, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic. Notably, countries like Belarus, Czechia, Greece, Italy, and Switzerland, which were previously consistent participants, chose to bypass this year’s forum. This dwindling European presence at BRF underscores the diminishing allure of China in Europe.

While China has recently projected itself as the champion of the Global South, emphasising the development and interests of emerging economies, it’s clear that this also serves its geopolitical ambitions. One might assume from this year’s BRF attendance that China’s diplomatic focus has veered strongly towards the Global South. However, such an assumption would be inaccurate. Even though China has amplified its engagement with the Global South, the BRF didn’t witness a marked increase in participation from these nations. The significant decline in European interest wasn’t counterbalanced by an uptick from leaders of the developing world, indicating a potential broader distancing from China’s influence.

But why is there a diminished interest in BRI as compared to say, 2017? For this, one has to understand the idea behind BRI. It represents a critical element of China’s more assertive international strategy. This ambitious effort is not just an economic endeavour but also a geopolitical manoeuvre in response to the US’ pronounced shift towards Asia. Through the BRI, China aims to establish new commercial relationships, expand export markets, enhance domestic incomes, and channel its surplus manufacturing capacity abroad. CFR’s David Sacks, a specialist in US-China affairs, notes that China has effectively been reorienting global trade networks, positioning itself at the core, rather than the US or Europe. Furthermore, the initiative is part of a larger statecraft under Xi, complementing the “Made in China 2025” policy.

In addition to its international aspirations, China has a strong domestic agenda driving the BRI. Central to this is the economic uplift of its western territories, which have not seen the same level of development as coastal areas. This is particularly true for Xinjiang, a region marked by rising separatist unrest; fostering growth here is crucial. Equally important is ensuring continuous energy reserves from Central Asia and the Middle East via channels beyond US military interference. On a larger scale, Chinese policymakers are attempting to re-engineer the national economy to evade the notorious middle-income trap, where nations experience growth but then falter before evolving into high-value economies. This trap has ensnared nearly 90 per cent of middle-income countries since 1960. As Beijing confronts mounting economic challenges, particularly concerning debt and rising unemployment, it will be interesting to know how China will now push for BRI.

The dissonance towards BRI is also because of the concerns regarding ‘debt-trap diplomacy’. This refers to a situation where countries are lured into accruing unsustainable debts, which they struggle to repay, often leading to forfeiting control of critical assets or influence to China. A notable instance is the Hambantota Port. Unable to repay Chinese loans, Sri Lanka leased the port to China for 99 years, a move criticised as an erosion of national sovereignty and a consequence of debt-trap diplomacy. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship BRI project, has raised similar concerns. Pakistan rethought its engagements due to fears of a debt trap, with worries about unfair contracts under the initiative.

Laos presents yet another case, where its public and publicly guaranteed debt has escalated to 123 per cent of GDP by 2023, based on data from the International Monetary Fund. A significant portion of this debt, over half, is due to China’s financing of multiple extensive infrastructure ventures within Laos in the past few years. As the country grapples with repayment, China’s approach to debt deferment lacks clarity, concealing the full extent of the financial turmoil and intensifying concerns regarding Beijing’s increasing influence in Laos.

To be fair to China, it provides bailouts to indebted BRI recipients while simultaneously reducing its loans. However, its bailout strategy primarily aims to delay immediate defaults by extending payment terms for poorer nations and injecting fresh funds for mid-tier economies. Such a bandaid solution, lacking genuine debt relief, fails to address the underlying issue of solvency.

The 2021 study’s findings reveal alarming implications for China’s lending practices with foreign nations. The majority of the more than one hundred debt financing agreements include clauses that curtail restructuring engagements with the leading creditors of the “Paris Club”.

The Paris Club is an informal group of official creditors whose primary purpose is to find coordinated and sustainable solutions to the payment difficulties experienced by debtor countries. By including terms that limit engagement with such a significant and established group, China appears to be isolating debtor countries from conventional international financial mechanisms.

Reservations about BRI extend beyond the fear of falling into a debt trap, with concerns ranging from transparency issues—stemming from a perceived lack of clarity in the terms and conditions of BRI projects that foster suspicions—to questions about the quality of the infrastructure projects, casting doubts on their long-term viability and safety. Economic viability is also a significant consideration; while some projects are grandiose, they may not provide a clear economic return, leaving countries with monumental yet non-economically beneficial infrastructure. Environmental concerns are equally prevalent, as the substantial impacts of large-scale projects may conflict with national sustainability objectives or global climate commitments. Moreover, political and strategic apprehensions arise as involvement with the BRI could be construed as a geopolitical alignment with potential implications for a country’s diplomatic engagements. Additionally, there’s a worry that local industries could suffer, overshadowed by the foreign corporations participating in BRI projects.

The overture of China’s BRI might remind some of the opening scene from the classic movie ‘The Wizard of Oz’. Like Dorothy’s enchanted journey to the Emerald City, many nations were lured by the glitzy promise of prosperity and development. But as in the film, where the mighty wizard turns out to be a mere mortal behind a curtain, the grand promises of the BRI seem to be falling a bit flat. Transparency issues, economic doubts, environmental worries, and geopolitical reservations cast a long shadow over China’s so-called “gift to the world”. It’s a wonder that the BRI’s promoters don’t simply click their heels together three times and wish for a more universally accepted initiative. As for the Global Times, with its hyperbolic self-praise and blatant attempts to paint an overly rosy picture of the BRI, one is reminded of the film’s famous line, “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!”

Such grandiosity is comedic at best and, at worst, a distorted reflection of an initiative with more cracks than the Yellow Brick Road.

The author is OSD, Research, Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister. He tweets @adityasinha004. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment