views

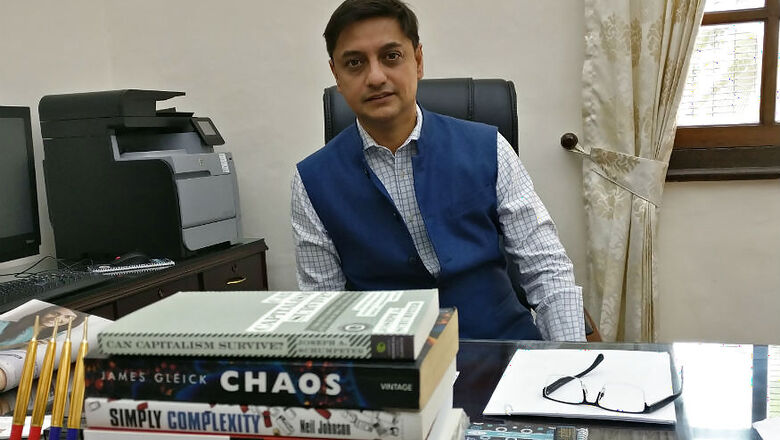

In February, the government appointed Sanjeev Sanyal as the Principal Economic Adviser in the Finance Ministry. His job is to provide inputs to the government on economic issues. However, Sanyal also brings with him a new worldview. He is an economist who has written copiously about history and urban planning, and authored books and articles that lie at the confluence of his numerous interests.

In February, the government appointed Sanjeev Sanyal as the Principal Economic Adviser in the Finance Ministry. His job is to provide inputs to the government on economic issues. However, Sanyal also brings with him a new worldview. He is an economist who has written copiously about history and urban planning, and authored books and articles that lie at the confluence of his numerous interests.

Born in Kolkata to a family that played a prominent role in India’s freedom struggle, Sanyal was educated in Kolkata, Delhi and London. He has been working in financial markets for the past two decades. Most recently, he was the Global Strategist at Deutsche Bank in Singapore. News18’s Tushar Dhara met Sanyal for his first in-depth interview to an Indian publication since he joined the government. Edited excerpts:

What is the philosophy behind your economics?

The philosophical basis of my economics is very different from conventional economics, which derives from ideas of equilibrium whose roots are Newtonian. The idea is that the economy needs to be in equilibrium. And, therefore, there are ideas such as NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment), natural rate of interest and so on.

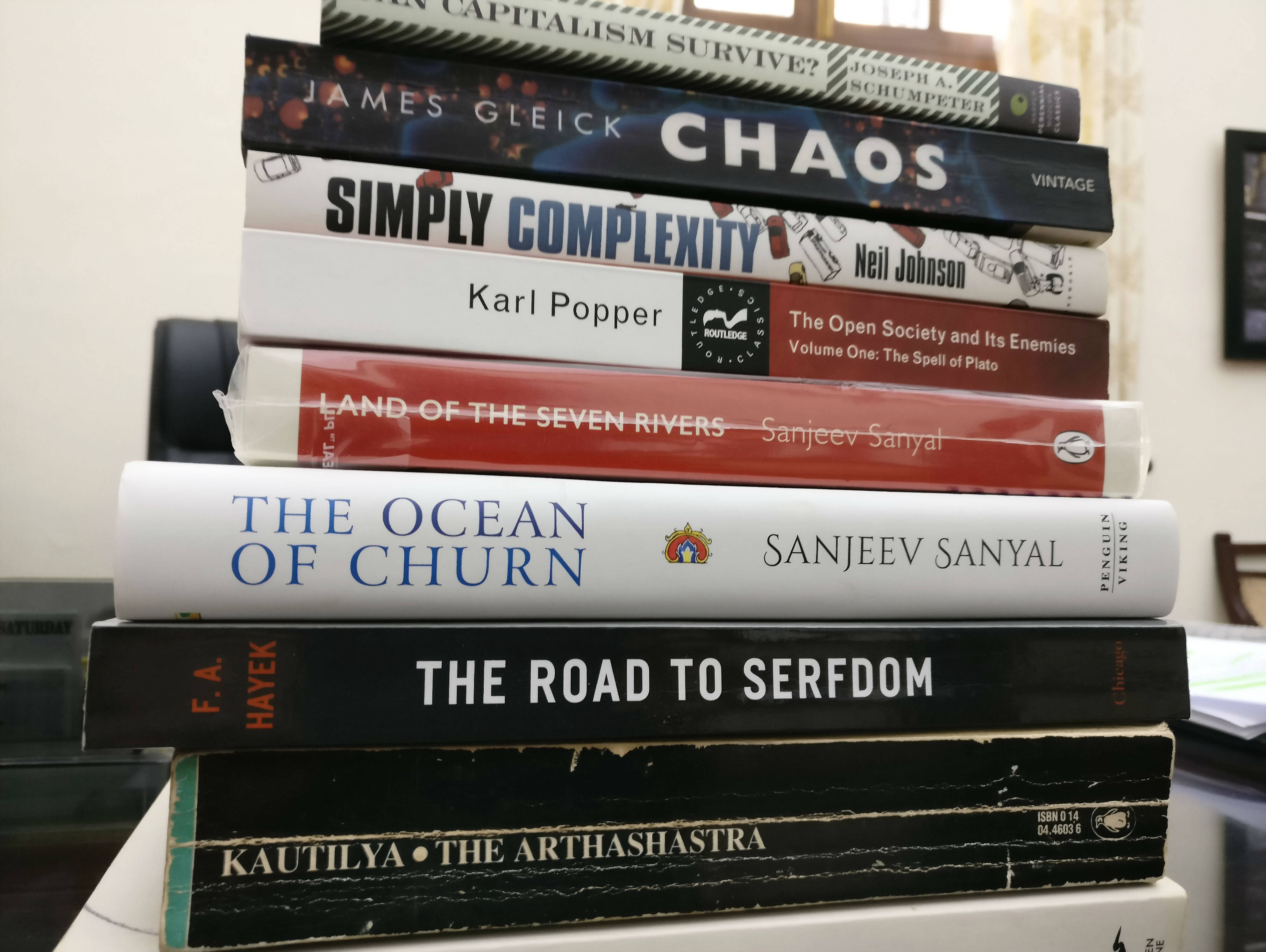

Now, my own view of economics is derived out of Chaos Theory and complex adaptive systems. In that worldview, there is no tendency for the economy to return to self-equilibrium. That throws out of the window a large part of conventional economics.

In my view, the really interesting things are risk, uncertainty and non-linearity. What matters is timing and risk management. When you make a policy, you don’t try and work out every outcome and pre-empt them, because you don’t know what they are. The emphasis is on flexibility: It’s more important to react fast to an evolving situation.

The reason I am suspicious of complex laws is because they lead to the system becoming opaque and rigid. Flexibility is important and this is the most important driving principle for me. It pervades my worldview: Economics, urban planning and history writing, where I look at the past in terms of complex adaptive systems.

Are you suggesting that policymakers should proceed after having a basic framework in place?

I will give you an example. Every businessman starts with a plan, but when he implements the plan, he adapts as things go along. That is basically what I am arguing. Do not make policy prescriptive, make it broad. It’s much easier to have a flexible policy and a simple framework.

What are the roots of your philosophy? Do you think you can leave an imprint of your philosophy on the Finance Ministry?

I have been influenced by many writers: Friedrich Hayek and Karl Popper, but also Indian writers like Kautilya. I am heavily influenced by the idea of Shiva, as the god of chaos and non-linearity.

This philosophical system is very much embedded in Indic philosophy. And there are many lines of Indic philosophy that derive from the idea of history flowing in non-linear ways.

I hope to be able to influence not just the Finance Ministry, but the way Indian policymakers think, by providing a new framework.

Can you please explain your idea of complex adaptive systems?

Let me give you examples of complex adaptive systems. The English language is a complex adaptive system; Hinduism is a complex adaptive system; a successful city like London is a complex adaptive system. There is enormous flexibility in the English language, that’s why it’s a robust system, what Nicholas Nassim Taleb calls ‘anti-fragile’.

Let’s look at London, which is continuously evolving. For hundreds of years, it has adapted. Let me give you the opposite example, which is Chandigarh or Brasilia. These are planned cities, and since the plans have been rigidly adhered to, they have gone sterile. One part of what underpins complex systems is the interplay of market forces of demand and supply.

Hinduism is very interesting, because Hinduism is a religion and it contains within it many faiths and beliefs. But Hinduism itself is not a faith or belief.

In most other religions, the terms ‘religion’, ‘faith’ and ‘belief’ are interchangeable. In Hinduism, they are not. Hindus are seekers, they are not believers. Hinduism is a religion, which is concerned with the meaning of life, ethics and so on, like other religions. But it does not give you one particular belief. It is perfectly fine for a Hindu to believe in one god, many gods, or to be an atheist or an agnostic. And all of these have long and well-represented traditions within Hinduism. If you can think of a new way of doing it, Hinduism allows you to add to it. Hinduism provides common idioms, rituals, ways of thinking, and a memory of thoughts that have already occurred. It provides tradition and community, and it is a living religion. Hinduism allows you to write new texts.

How do you square that with the pushing of a certain kind of Hinduism in today’s India?

I believe that Hinduism is evolving and is going through enormous evolution right now. New ideas of all kinds are being adapted and adopted. It’s perfectly fine to have completely new ideas to come into Hinduism, as long as it accepts the broad framework, which is the idea that it is evolving and eternal, and eternally evolving.

There is a view that attempts are being made to make Hinduism more like the Semitic religions. Do you agree with that?

No, I don’t. Because Hinduism as a whole has absorbed ideas and it can also absorb Semitic ideas. Hinduism does not believe in one god or a prophet. It is structured in the following way. It has two sets of texts: Smriti and Sruti. Ninety nine per cent of Hindu texts are Smriti, which literally means memory of the great thoughts of the past. They are not canonical, in the sense that they are not the word of god. Even the Bhagwad Gita is not the word of god; it is ‘as heard by Sanjaya’. That is deliberate, you have to understand that.

Srutis are only the first three Vedas, some will say only the Rig Veda alone. Even the Upanishads are not Sruti. Only the samhitas — the Rig Veda, Sama Veda and Yajur Veda — are Sruti.

Interestingly, Sruti is that which is heard or inspired. Take the Nasadiya Sukta (a creation hymn in the Rig Veda). It says: In the beginning, there was neither light nor darkness, neither up nor down… in the end, it says, what there was we do not know, perhaps the great rishis knew, perhaps not. Even the gods came afterwards, so even they may not know. Perhaps the great creator knows, perhaps he too knows not.

All of Hinduism starts with a question, not with an axiom. And from that point you are seeking the answers to those questions. So the philosophical unity of Hinduism is derived from questions, not from answers.

In Christianity, there is one god and Jesus is his son. If you don’t believe that, you are not a Christian. In Islam, there is one god and Mohammad is his prophet, his last prophet. If you don’t believe that, the rest is irrelevant. There is no such axiom in Hinduism. The beginning point of Hinduism is a question, it’s not an axiom. You’re not expected to believe in anything, except that there is something worth searching for. This is the operating system of Hinduism.

The Sruti texts, which are the first three Vedas, provide the operating system of Hinduism. The remaining texts are apps. You can add an app, you can remove an app.

An average person does not need to read the Vedas, just as the average person does not need to understand how an operating system works. But this is the basis on which the whole structure is set up, and it is an example of a complex adaptive system.

The social norms of Hinduism have changed many times. Right now they are changing again as we urbanise. Old caste norms are changing. Festivals are changing. For example, Durga puja was largely an eastern Indian festival, now it’s all over. A hundred years ago, Ganesh Chaturthi was performed at homes in Maharashtra. Under Tilak, it became a public festival, as a sign of resistance to foreign rule. Durga is not just a Bengali goddess; she represents a certain way of thinking about the world derived from the Shakta tradition.

Can you talk a bit about your family background?

My family were Bengalis from Varanasi. They were well-known scholars in the 18th century. But in my grandfather’s time many members of my family joined the national revolutionary movement. One of my granduncles, Sachindranath Sanyal, was a mentor of Bhagat Singh and Chandrashekhar Azad, and he was sent off to Kalapaani. He was one of the main planners of the Ghadar Movement and one of the founders of the Hindustan Republican Army. My family members were also involved in planning the Kakori Kaand. Several of them were jailed and one of them, Rajendra Lahiri, was hanged. Bhagat Singh mentions him in one of his tracts.

How did the city of Varanasi influence your worldview?

The city of Varanasi is a great example of a complex adaptive system. It’s built layer upon layer, like a palimpsest. There is some evidence to suggest that Varanasi may be as old as Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, and it’s still around, while the latter cities have disappeared. So perhaps there is something about Varanasi, the ability to continuously adapt.

Can you talk about the relation between economics and history, as you perceive it?

All policymaking must incorporate history. A lot of social sciences are heavily influenced by Newtonian logic. Take the Marxists. Their way of thinking is heavily influenced by the idea of a Victorian steam engine running down a fixed track. That is why historical materialism rigidly leads from feudalism to capitalism to socialism and finally communism. Similarly, take (John Maynard) Keynes, whose worldview was derived from hydraulics. You pull the lever, increase or reduce pressure. Similarly, the economy is to be kept to some equilibrium by increasing or decreasing pressure, in this case interest rates. If you remove the idea of equilibrium, the whole thing falls apart.

In my worldview, there is no such thing. At every point in time you respond to the situation as it exists without any preconceived notion of equilibrium. It is a world of unintended consequences.

Similarly, in history, at any point in time, you could have gone down multiple pathways. Nothing is predetermined. If you try and interpret the past based on this, you have to take into account that the same individual or the same policy at different points in time may not have worked.

To me, it is not obvious that history always progresses. It moves forward, but civilisations rise and collapse. In this case, what does the state invest in? The role of the state is the following: Enforcement of contracts and justice; rule of law; internal security and defence; framework infrastructure (Aadhaar cards, highway networks etc).

I am not a libertarian. I want a strong but limited state.

Another person who has hugely influenced me is Lee Kuan Yew. Singapore at that time required a certain set of rules: the rule of law, keeping markets open, allowing, but also intervening strategically. Somewhere, the public sector has a role to play. ISRO is a great case of state intervention in India. Singapore Airlines is a public sector company. I don’t have any ideological problem with the public sector. If something doesn’t work, shut it down. If something is working let it continue…it’s all about evidence.

But there is also criticism that Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore model was authoritarian.

Very often these criticisms came from the BBC, which is the state-owned propaganda unit of the British government. So what? It depends on how you view the whole matter. My own view is that Singapore is as free or unfree as any other nation.

Who among contemporary Indian economic thinkers have influenced you?

BR Shenoy, Jagdish Bhagwati. One of the biggest influences has been Dr BR Ambedkar, who has been hijacked by a certain political ideology. But Ambedkar as an economist is very much worth looking into. He was all about laws, hence the Constitution. But having created those laws, he talked about market economics.

The reason you didn’t have the term ‘Socialism’ in the original Constitution Ambedkar authored was because he made the point that we cannot commit India to a pre-determined way of doing things in the future, other than the basic framework of the Constitution.

He personally didn’t believe in Socialism, but he is also not saying it should be capitalist. What he is saying is that whatever works, works.

You have had a Nehruvian consensus in India since Independence. What about that?

What I am trying to do is break down that consensus, whether it’s the narrative on history, or the way we design our cities, or the way we run our economics. Some of what I am talking about is an attempt to create a replacement using chaos theory and complex adaptive systems, which ironically are closer to our traditional way of thinking. This is embedded in our civilisational way of thinking about the world.

Which part of Nehruvian consensus do you disagree with?

I disagree with the whole idea of a preconceived worldview, a top down approach of a group of people sitting in the Planning Commission telling everybody how they will lead their lives, which is a rigid way of thinking. The same idea applies to our urban planning, with its rigid master plans.

Let’s go back to the Singapore and Chandigarh of 1965. The Chandigarh of today is pretty much the same, you may have things outside Chandigarh like Mohali, but Chandigarh is still the same. The city still goes by the same plan that Le Corbusier gave you. And we are very proud that we have stuck to that plan.

In 1965, Singapore was a British military outpost and a slum ridden, communally sensitive and poor third world city. Since then, it first transformed itself into a major shipping port, then it became an electronics manufacturing hub, then it transformed itself into a financial centre. More recently, it has become an entertainment and education centre. The Singapore of today bears almost no resemblance to the Singapore of 1965. It’s a complex adaptive system. It has continuously adapted.

Take Gurgaon. The problem with Gurgaon is not the plan, it is bad management. Singapore is well-managed. Gurgaon, it is not a well-designed Chandigarh. If you manage Gurgaon well, it can become Singapore. If you managed Chandigarh well, it will become Brasilia.

In the Indian context, a city like Gurgaon was built entirely by private developers.

It’s a great example of a random robber baron city-building.

The robber baron business seems to be the standard template of Indian business.

Once you have accepted that, you need to create Gurgaons, rather than Chandigarhs, then we need to manage the robber baron problem. The answer is to manage it, rather than creating another Chandigarh. Because apart from Chandigarh’s own failure, we have created Durgapur, Dispur, Burnpur, Naya Raipur. Have any of them become great urban centres?

What about Noida?

Noida may be more interesting because it is part of a wider system.

Comments

0 comment