views

Clause Definition

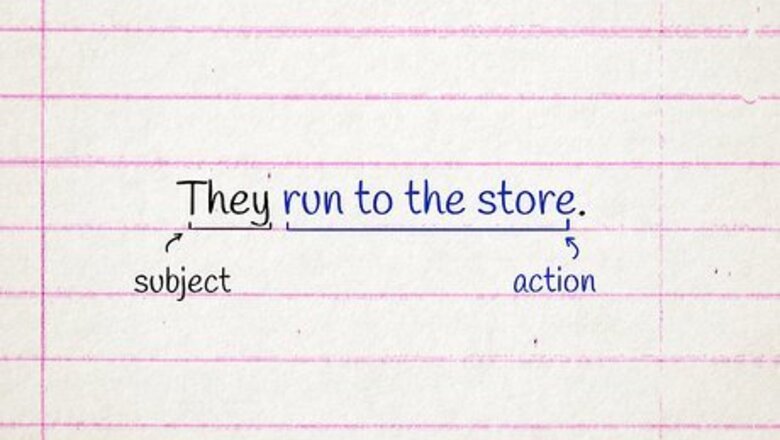

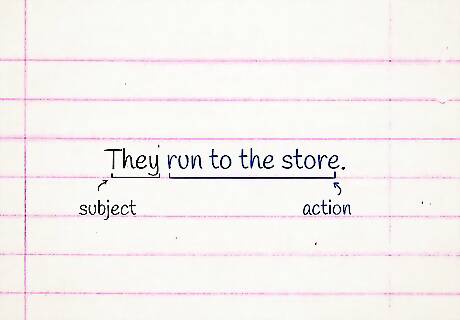

A clause is a group of words that tells you two things. First, it has a subject: that's who or what is doing something. Second, it has a predicate: that's the action the subject is doing. “They run” is a clause. It tells you the who (they) and the action (run). “They run to the store” is also a clause. The "action" uses more words, but it's still one idea. "My dog is a good boy" is also a clause. The word "is" (or "are") counts as an "action." To identify the clause, students need to understand the subject-verb basic construction. For example, in the sentence Mary runs to the store, they can find Mary is the subject, and runs which is the verb. A clause is something that paints the picture bigger.

Phrase Definition

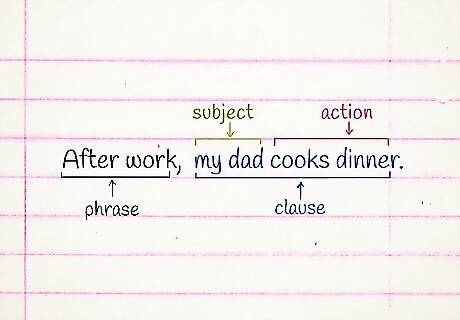

A phrase doesn't have enough info to be a clause. A clause always tells you that someone (or something) is doing something. If a group of words doesn't do this, it is a phrase. A phrase only tells us one little thing. The sentence "After work, my dad cooks dinner" has one phrase and one clause. The clause is "my dad cooks dinner." It has a subject ("my dad") and an action ("cooks dinner"). The phrase is "After work." It doesn't tell us about a subject or an action.

Adjective Test

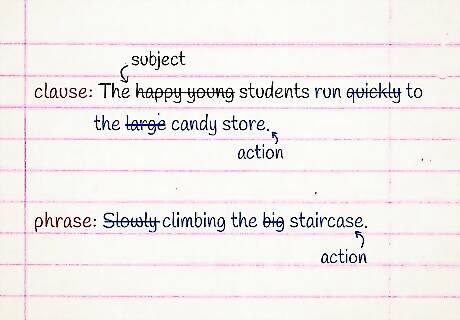

You can ignore adjectives when you are looking for clauses. Adjectives (and adverbs) are the sprinkles on top. They make sentences pretty, but they aren't the main idea. If you have homework that asks "Is this a phrase or a clause?" try crossing out the adjectives. This can help you see what's important. Look at "The happy young students run quickly to the large candy store." Cross out the adjectives and adverbs. Now it's "the students run to the candy store." That tells you a who and an action, so it's a clause. Now look at "Slowly climbing the big staircase." Cross out the adjectives and adverbs. Now it's "climbing the staircase". This doesn't tell us who is climbing. That means it can't be a clause. This is a phrase.

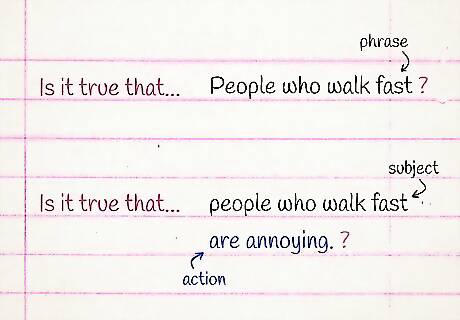

"Is it true that..." test

Add this to a group of words and see if it makes sense. If it sounds right, the group of words is a clause. If it doesn't sound right, then the group of words is probably a phrase. Here are some tricky ones to try it on: My friend holding the pizza → "Is it true that my friend holding the pizza?" This doesn't make sense, so it's a phrase. People who walk fast → "Is it true that people who walk fast?" This also fails the test. It's just another phrase. Try this test with "people who walk fast are annoying." See how it makes a normal sentence? This is a clause. It tells us the subject ("people who walk fast"). It also tells us the action (they "are annoying").

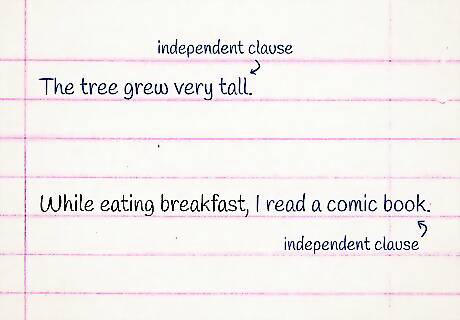

Independent Clauses

An independent clause can be a sentence by itself. It tells you the subject of the sentence. ("Who" or "what" the sentence is about.) It also tells you the main action of the sentence. (What the subject is doing.) Most clauses are independent clauses. "The tree grew very tall" is an independent clause. It is a whole sentence by itself. Look at the sentence "While eating breakfast, I read a comic book." The main part of the sentence is "I read a comic book." You can write it on its own and it is a complete sentence. This means "I read a comic book" is an independent clause.

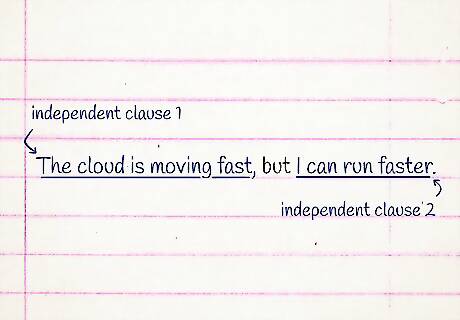

Connecting Independent Clauses

Words like "and" or "but" connect two independent clauses. Sentences can have more than one clause. To identify the clauses in one long sentence, look for "connecting words." (These are also called "conjunctions.") These words, like and, but, or, and yet, go between two independent clauses. Can you identify the two clauses in "The cloud is moving fast, but I can run faster"? "But" is the connecting word in this sentence. It connects two independent clauses. Everything before the "but" is one independent clause: "The cloud is moving fast." Everything after the "but" is another independent clause: "I can run faster."

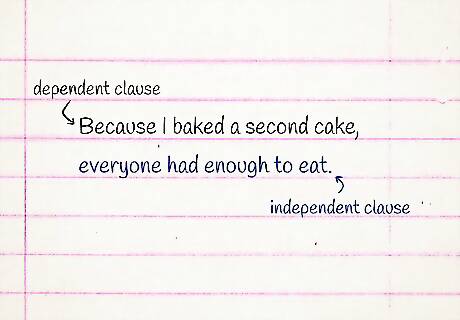

Dependent Clauses

A dependent clause is a clause without a complete thought. Like all clauses, a dependent clause has a subject (the "who" or "what") and an action. But it can't be a complete sentence on its own. A dependent clause begins with a word like because, although, if, or when. These words connect it to another clause in the sentence. "Because I baked a second cake" is a dependent clause. It has a subject ("I") and an action ("baked a second cake"). But it's not a complete sentence. It has an unanswered question: Because of what? "Because I baked a second cake, everyone had enough to eat" is a complete sentence. It has two clauses. "Because I baked a second cake" is a dependent clause. "Everyone had enough to eat" is an independent clause.

Relative Clauses

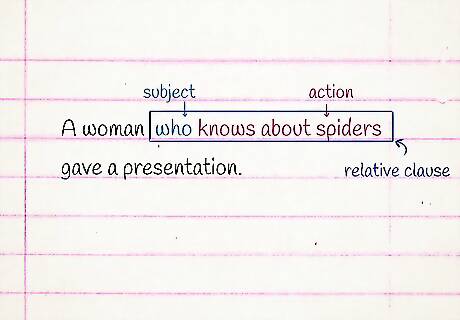

Words like "who" or "which" begin relative clauses. These are a type of dependent clause. That means the clause can't be a complete sentence on its own. Instead, a relative clause describes a noun in a different clause. In the sentence "A woman who knows about spiders gave a presentation," the word "who" starts a relative clause. "Who knows about spiders" is the relative clause. It tells you something about the woman. It can't be a complete sentence on its own. "Who" is the subject and "knows about spiders" is the action (the "predicate"). These clauses can begin with the words who, whom, whose, that, which, when, where, or why.

Relative Clauses without a "Who" Word

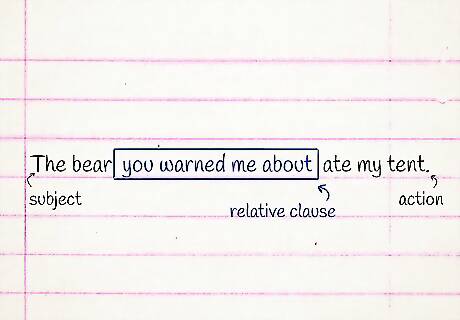

Sometimes the "who" word is cut from a relative clause. This makes it harder to identify it as a relative clause. Here's how to still tell that it's a relative clause: A relative clause comes after a noun. Look at the sentence "the bear you warned me about ate my tent". The relative clause "you warned me about" comes right after the noun "bear." You can cut the relative clause from the sentence and it still makes sense. Try removing "you warned me about." What you have left is still a complete sentence: "The bear ate my tent". You can put back a "who" word. In this case, you can use the word "that." "The bear that you warned me about ate my tent".

Tricky Clauses with "-ing" Adjectives

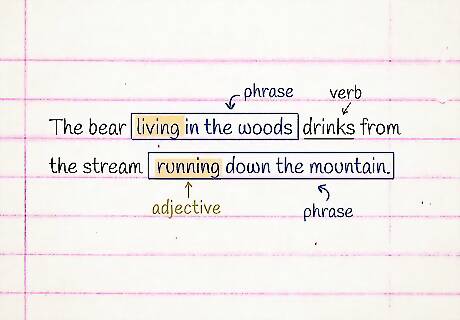

Words ending in -ing can't be the main verb. Every clause has a verb, so looking for one is a good start. But when you add an "-ing" ending to a verb, it's no longer a verb. It's now an adjective describing a noun. Here's a practice problem: Identify the clauses in the sentence "The rushing river flooded the field." At first, it looks like there are two verbs: "rushing" and "flooded." But the word "rushing" is an adjective here. It is not a verb anymore, so it can't be the main action of a clause. That means this whole sentence is only one clause. Try this more difficult problem: Identify the clauses in the sentence "The bear living in the woods drinks from the stream running down the mountain." In this sentence, neither "living" and "running" are real verbs. They are adjectives that start the phrases "living in the woods" and "running down the mountain." The only real verb is "drinks," so the whole sentence is one clause.

Tricky Clauses with "-ing" Nouns

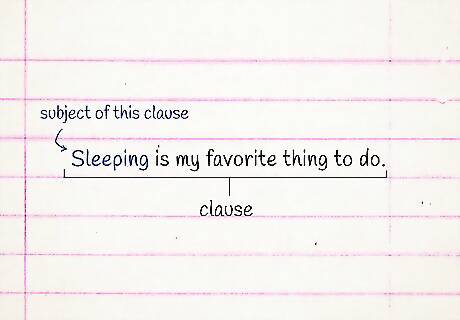

Words ending in -ing can act as nouns. This might sound weird and complicated — it started as a verb and now it's a noun? But don't worry too much about the grammar. If you're a native English speaker, this already sounds normal to you: "Sleeping is my favorite thing to do" is a clause. The subject of this clause is "sleeping." It might help to notice that "sleeping" is in the same place a regular subject usually goes, right before the verb: "Sleeping is" instead of "The tree is."

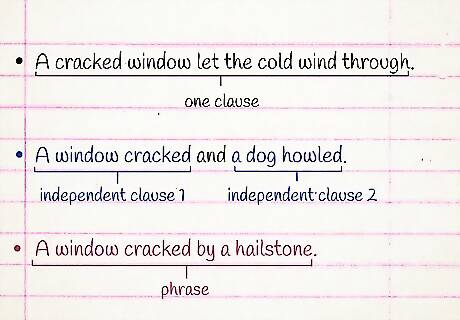

Tricky Clauses with "-ed" or "-en" Words

Words ending in -ed or -en can be verbs or adjectives. When they're verbs, they tell you the action that happened just now. When they're adjectives, they describe what a noun is already like: "A cracked window let the cold wind through" is one clause, with the main verb "let." The word "cracked" isn't a verb here, so it can't be part of a second clause. It's an adjective describing a window that is already cracked. "A window cracked and a dog howled" is a sentence with two independent clauses: "a window cracked" and "a dog howled." In these cases, the "-ed" words are verbs that tell you what just happened. If the word is in front of the subject, it's almost always an adjective, not a verb. If it's after the subject, it could be either. A window cracked by a hailstone is a phrase, not a clause. It's describing what already happened to the window, not what the window is doing now.

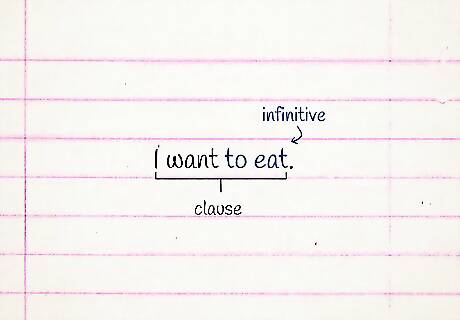

Tricky Clauses with Infinitives

Verbs in the form "to ___" are not the main verb. These are called "infinitives." A group of words with an infinitive and no other verb is a phrase, not a clause. There are many different ways to use these, but you don't need to understand all of them. Here is one of the most common uses: I want to eat is one clause. "Want" is the main verb. "To eat" is just part of the full predicate "want to eat." It is not a main verb, so it cannot be part of a new clause.

Comments

0 comment