views

X

Research source

In the film, Professor Kingsfield tells his first-year law students: “You come in here with a head full of mush and you leave thinking like a lawyer.” Although law professors remain fond of telling students they’re going to teach them how to think like a lawyer, you don’t have to attend law school to enhance your own logic and critical thinking skills.

Spotting Issues

Approach a problem from all angles. To see all the possible issues in a set of facts, lawyers look at the situation from different perspectives. Putting yourself in others’ shoes allows you to understand other points of view. On law school exams, students learn to structure their answers using the acronym IRAC, which stands for Issue, Rule, Analysis and Conclusion. Failure to spot all possible issues can derail the entire answer. For example, suppose you’re walking down a street and notice a ladder leaned against a building. A worker on the top rung is reaching far to his left, cleaning a window. There are no other workers present, and the bottom of the ladder juts out onto the sidewalk where people are walking. Issue spotting involves not only looking at this situation from the viewpoint of the worker and the person walking on the street, but also the building owner, the worker’s employer, and potentially even the city where the building is located.

Avoid emotional entanglement. There’s a reason you might say you were “blinded” by anger or another emotion -- feelings aren’t rational and keep you from seeing facts that may be important to solving a problem. Accurately spotting the issues is important to determine which facts are relevant and important. Emotions and sentiment can cause you to become attached to details that bear little to no importance to the outcome of the situation. Thinking like a lawyer requires putting aside personal interests or emotional reactions to focus on real, provable facts. For example, suppose a criminal defendant stands charged with molesting a small child. Police arrested him near a playground, and immediately began asking him why he was there and his intentions regarding the children playing nearby. The distraught man confessed he planned to harm the children. The details of the case may be revolting, but the defense attorney will set aside the emotional trauma and focus on the fact that the defendant was not informed of his right to remain silent before he was questioned.

Argue both sides. Non-lawyers may perceive this ability as a moral failing in lawyers, but it doesn’t mean lawyers don’t believe in anything. The ability to argue both sides of an issue means you understand that there are two sides to every story, each of which has potentially valid points. When you learn how to make opposing arguments, you also learn how to hear them, which increases tolerance and allows more problems to be solved cooperatively.

Using Logic

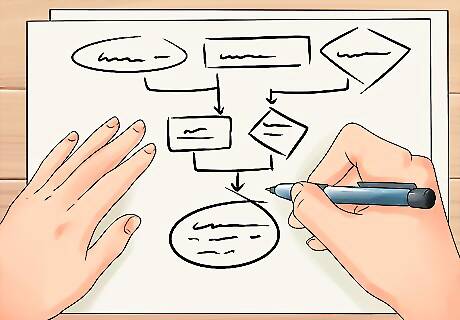

Deduce particular conclusions from general rules. Deductive reasoning is one of the hallmarks of thinking like a lawyer. In law, this pattern of logic is used when applying a rule of law to a particular fact pattern.

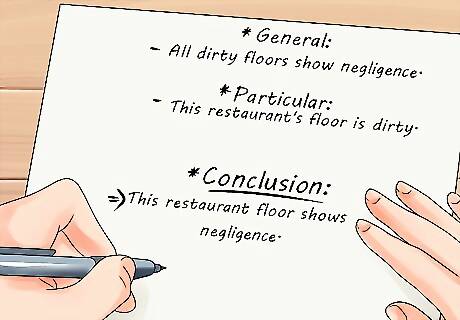

Construct syllogisms. A syllogism is a particular type of deductive reasoning often used in legal reasoning, and asserts that what is true for a general group will also be true for all specific individuals in that same group. Syllogisms consist of three parts: a general statement, a particular statement, and a conclusion about the particular based on the general. The general statement typically is broad and nearly universally applicable. For example, you might say “All dirty floors show negligence.” The particular statement refers to a specific person or set of facts, such as “This restaurant's floor is dirty.” The conclusion relates the particular back to the general. Having stated a universal rule, and having established that your particular person is a part of the group covered by the universal rule, you can now arrive at your conclusion: “This restaurant floor shows negligence.”

Infer general rules from patterns of specifics. Sometimes you don’t have a general rule, but you can see several similar situations in which the same thing happened. Inductive reasoning allows you to conclude that if the same thing happens enough times, you can draw a general rule that it will always happen. Inductive reasoning doesn’t enable you to make any guarantees that your conclusion is true. However, if something happens regularly, it’s probable enough for you to rely on when creating a rule. For example, suppose no one’s told you that, as a general rule, a dirty floor shows negligence on the part of a shop employee or shop owner. However, you observe a pattern in several cases where a customer slipped and fell and the judge ruled the owner was negligent. Because of his negligence, the owner had to pay for the customer's injuries. Based on your knowledge of these cases, you conclude that if a shop floor is dirty, the shop owner is negligent. Only knowing a few examples may not be sufficient to create a rule you can rely on to any great extent. The larger the proportion of individual cases in a group that share the same trait, the more likely the conclusion is to be true.

Compare similar situations using analogies. When lawyers argue a case by comparing it to an earlier case, they’re using an analogy. Lawyers try to win a new case by demonstrating that its facts are substantially similar to the facts in an old case, and thus the new case should be decided the same way as the old case was. Law professors teach law students to reason by analogy by proposing hypothetical sets of facts for them to analyze. Students read a case and then apply that case’s rules to those different scenarios. Comparing and contrasting facts also helps you determine which facts are important to the outcome of the case, and which are irrelevant or trivial. For example, suppose a girl in a red dress is walking through a store when she slips and falls on a banana peel. The girl sues the store for her injuries and wins because the judge rules the store owner was negligent in not sweeping the floor. Thinking like a lawyer means identifying which of the facts were important to the judge in deciding the case. In the next town over, a girl in a blue dress is walking to her table at a café when she slips and falls on a muffin wrapper. If you’re thinking like a lawyer, you’ve probably concluded that this case has the same outcome as the previous one. The girl’s location, the color of her dress, and what she tripped on are all irrelevant details. The important, and analogous, facts are an injury that occurred because a store owner was negligent in his or her duty to keep the floors clean.

Questioning Everything

Break down assumptions. Like emotions, assumptions create blind spots in your thinking. Lawyers seek evidence to prove every factual statement, and assume nothing is true without proof.

Ask why. You may have had experience with a young child who asked “why?” after everything you said. Although that can get annoying, it’s also part of thinking like a lawyer. Lawyers refer to why a law was made as its ‘‘policy.’’ The policy behind a law can be used to argue that new facts or circumstances should also fall under the law. For example, suppose that in 1935, the city council enacted a law prohibiting vehicles in the public park. The law was enacted primarily for safety concerns, after a small child was hit by a car. In 2014, the city council was asked to consider whether the 1935 statute prohibited drones. Are drones vehicles? Would prohibiting drones advance the law’s policy? Why? If you’re asking those questions (and recognizing arguments that can be made on both sides), you’re thinking like a lawyer. Thinking like a lawyer also means not taking anything for granted. Understanding why something happened, or why a certain law was enacted, enables you to apply the same rationale to other fact patterns and reach a logical conclusion.

Accept ambiguity. Legal issues are seldom black and white. Life is too complex for legislators to account for every possibility when they write a law. Ambiguities allow for flexibility, so laws don’t have to be rewritten every time a new scenario comes along. For example, the Constitution has been interpreted to relate to electronic surveillance, a technological advance the Framers couldn’t have imagined. Much of thinking like a lawyer involves being comfortable with nuances and gray areas. However, just because those gray areas exist doesn’t mean distinctions are meaningless.

Comments

0 comment