views

When Dron Mishra’s elderly father suffered paralysis, he turned to Lucknow’s best private hospital for treatment.

“Government hospitals are too crowded and have a long waiting list, so we went to a private hospital to start his treatment at the earliest,” Mishra recalls. “The hospital we chose was one of the most popular in Lucknow… I just fell into the trap.”

Mishra’s father was admitted to the hospital in 2012 and his pathology reports indicated a high level of serum creatinine, which is indicative of kidney disease. Despite the alarming reports, his neurologist did not advise further investigations, nor did he refer the patient to a nephrologist.

A year later, when his condition deteriorated further, the doctors ran a number of tests and confirmed that he was suffering from end-stage renal disease and required dialysis.

“We were shocked to hear this. My father was under constant supervision for nearly three years. How can someone’s kidneys fail all of a sudden?” he asks. Mishra then took his father to a private hospital in Delhi in 2014.

“I got to know from the doctors in Delhi that my father was being administered wrong injections over the years, which resulted in his kidney failure,” he says. “It was only then that I filed a case of medical negligence.”

In November 2019, apex consumer court NCDRC held the treating doctors Sandeep Agarwal and Muffazal Ahmed of Sahara Hospital guilty of medical negligence and directed them to pay Rs 30 lakh compensation to Gyan Mishra, who passed away during the pendency of the case.

Mishra’s case is just one of the many that are reported. But what largely goes unreported are the challenges these victims face in their fight for justice.

No Police Action Against Doctors

On 16 July, 2019, almost two years after his son died due to medical negligence, Sunil Malik finally received justice when the Court of Judicial Magistrate, Rewari, held Dr. Ravi Yadav of Vatsalya Children Hospital guilty under Section (304A) of IPC code (Punishment for culpable homicide not amounting to murder). But Malik’s journey to this moment was not an easy one. His first major challenge was lodging a complaint at the local police station.

“The police first refused to even register an FIR,” he says. “They said we are not doctors, how will we know who is right and who is wrong. We don’t have proof.”

As per the past Supreme Court judgments, the police officials are restricted from arresting doctors without prima facie evidence of medical negligence, meaning the "police can’t arrest and harass doctors" unless the facts are in line with earlier apex court guidelines.

Ineffective Regulatory Bodies

Usually, the first step taken in case of medical negligence is filing a complaint with the state or national medical council. Just like Malik, Ashwani Diwan’s experience with these regulatory bodies wasn’t a pleasant one either.

Diwan lost his father in July 2018 after being allegedly misdiagnosed with cancer and wrongly treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy at a private hospital in Kolkata.

He lodged a complaint with the West Bengal Medical Council (WBMC) and West Bengal Clinical Establishment Regulatory Commission (WBCERC).

“The state medical council did not even take up my case. At WBCERC, the doctor who was treating my father was one of the judges,” says Diwan. “When I wrote to them asking how was that ethical, they just dismissed my case.”

Ramanuj Mukherjee, a Delhi-based lawyer, agrees that complaining to these regulatory bodies often doesn’t produce favourable result. “They rarely take any action against the doctor and their decision is rather biased,” he says.

However, Dr. RV Asokan, Honorary Secretary General of the Indian Medical Association (IMA), strongly disagrees, saying a doctor’s profession is not black and white like that of lawyers. “In any clinical situation, there are always two, three or more options and a doctor can always justify his treatment,” he says.

He further explains that these regulatory bodies are just quasi-judiciary bodies, who cannot give a jail sentence or impose a fine. “At best they can stop the doctor from practising for a certain period of time,” he adds.

Dr. SK Thakur, a retired government hospital doctor from Bihar, however, says it is important for the MCI (Medical Council of India) to take disciplinary action against the erring doctor/hospital well in time, even if it means cancellation of the licence for a short duration. “It will give satisfaction to the victims and build faith in the profession,” he says.

Long Wait For Justice

While a few like Mishra and Sunil Malik receive justice, there are many who spend years embroiled in an uphill legal fight with no end in sight.

Rinku Singh, a resident of Azamgarh, has been fighting a case against a private hospital in Delhi after the death of his father in 2015 due to alleged medical negligence.

“Our family has suffered so much over these years. It takes a lot of time and money to visit Delhi for the hearings,” he says.

It’s been four years already but the case – both at consumer court and Saket court - seems nowhere close to judgement.

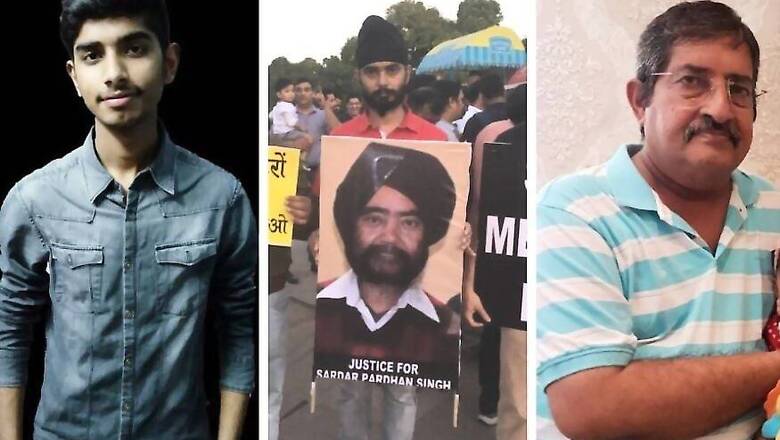

Rinku Singh holding his father's photo at a candle light march demanding justice for medical negligence victims. (15 September 2018, India Gate)

“In many areas such as medical negligence, our courts have an insane pendency rate, sometimes hearing may not even start in several years,” says Mukherjee.

Lawyer R Harbans Sahai, who is himself fighting a medical negligence case against a Delhi hospital after the death of his wife, says a doctor’s conviction also does not necessarily mean victory for a victim’s family.

“Even if there is a conviction under Section (304 A), the maximum punishment does not extend beyond two years, and in the meantime the doctor easily gets a bail while the case drags on for years,” he explains.

There are primarily three legal options for victims of medical negligence: Criminal, Civil or Consumer case.

“Unless the negligence is of a glaring nature, it is very hard to register criminal negligence case against a doctor in India,” Mukherjee stresses.

Dr. Asokan strongly opposes criminal proceedings against a doctor. “In any crime, the important thing is the criminal intent. How many doctors enter the profession to kill their patients,” he questions.

The other remedy is to file a civil case. “In India, it takes 3-4 years just to start a civil case, and god knows how long it will take to get a judgment,” Mukherjee says.

Healthcare was ‘removed’ from the list of services in the Draft Consumer Protection Bill following an amendment on June 24, 2019. However, the Bill also included a provision “but not limited to” before the list, leaving it to open to judicial interpretation. It was passed by the parliament in August 2019.

Malini Aisola is part of a patient group called Campaign for dignified and affordable healthcare (CDAH), which actively assists families that have suffered exploitation, overcharging and medical negligence due to private hospitals. She says that unnecessary confusion over the new Act has been created by vested interests.

“It is our understanding that healthcare is very much part of the services covered under the new Act. Patients and medical negligence victims would certainly be able to approach the consumer forums for redressal,” she said.

Mukherjee agrees that as ‘healthcare’ is not specifically excluded, courts are free to include it.

However, Asokan believes the addition of healthcare in the consumer law had done more damage to the patient. “When a patient becomes a consumer, it affects the relationship between the patient and the doctor,” he says. “It had become so easy for a patient to file a consumer case against their doctor that now an entire generation of doctors are mortally afraid of their patients and don’t want to take any risks.”

Dr. Thakur agrees that there is a prevailing fear among doctors, adding that the delay in justice is another reason why people are losing faith in the profession.

Impossible To Prove

In Mukherjee’s opinion, the biggest challenge is proving a medical negligence case in the court. “It is very hard for victims to establish negligence as other doctors are unwilling to support in collection of evidence or testify against other doctors,” he says.

Shishir Chand’s experience backs this up. “The doctor, who had confirmed negligence in my brother’s treatment on the affidavit, later denied answering questions by the prosecution at the court,” he says. “He was harassed by his employer.”

In April 2013, Chand had filed a complaint at the apex consumer court, the NCDRC, against a hospital in Jamshedpur, where his brother allegedly died due to medical negligence. His case is still pending.

Not just the expert witnesses, even the victim’s family is often harassed for filing a complaint, as was the case with Sahai.

“The doctors, against whom I had filed medical negligence case, sent goons to threaten me to take back the complaints,” he alleges.

Financially and Emotionally Draining

The long wait for justice adds to the emotional and financial burden of patients and their families.

“In a span of three years, I have spent lakhs of rupees to fight this case,” says Dron Mishra. “These private hospitals can hire a battery of lawyers. Not many can afford to fight a battle against them.”

Sahai adds that a lot of such cases against government hospitals don’t come out in the open for this reason. “Usually, people from the low-income families go to public hospitals. From where will they get the money to fight a case against a doctor?” he says.

Inequitable Compensation

In 2013, the Supreme Court awarded the highest ever compensation of Rs. 5.96 crore to Dr. Kunal Shah for medical negligence that led to the death of his wife in 1998.

But not everyone manages to get adequate compensation. Mishra, who represented his father’s medical negligence case, says part of the problem lies in the fact that the judge has the absolute discretion in awarding compensation.

“The judge agreed that there was negligence on part of the doctors. But when it came to compensation, he said he is not sure about the extent of damage that their treatment has caused,” he says.

In a paper on ‘Compensation and Medical Negligence in India’, the authors argued that the issue of “subjectivity” of the presiding judge erodes faith in the justice system, and called for an overhaul of the way India addresses medical negligence cases.

The Way Forward

Mukherjee backs calls for a specialist tribunal for patients/families seeking justice. “A major malpractice is getting patients to spend money on unnecessary treatment and procedures. We need laws to address such issues,” he adds.

Chand, who is also the Delhi-Coordinator of ‘People for Better Treatment’, outlines a number of measures, including a strong regulatory body with ethical credibility, strengthening of public health services, social regulation of private healthcare, discouraging a culture of silence among doctors and encouraging doctor-patient dialogue.

“On the legal front, it is important to set up a fast track court for such cases,” he adds.

Dr. Asokan believes part of the problem lies in the mushrooming of for-profit hospitals (with large share shareholders) offering tertiary care. “For-profit healthcare is a crime. When you make money out of someone’s misery, it is absolutely wrong,” he stresses, adding that for-profit hospitals are different from the small and medium hospitals providing primary and secondary care.

“The failure of public hospitals has led to this situation. Our government fails to invest in the infrastructure and human resources of government hospitals, instead spends it in healthcare insurance,” he says. “Thousands of money is flowing in the wrong direction.”

Meanwhile, the battle is far from over for both Dron Mishra and Sunil Malik.

Dr. Ravi Yadav, who is out on bail, has challenged the Judicial Magistrate’s judgment in the high court. “No medical council has yet held me guilty for medical negligence. Then on what basis is he (Sunil Malik) fighting a medical negligence case and defaming a doctor?,” Yadav says. “A doctor can only do so much to treat a patient. We do our best but the rest is on God.”

Malik, however, believes he will win, saying, “I am determined to weed out these black sheep from the system, so other families don’t have to suffer like we did.”

On the other hand, Mishra has now submitted a review petition against the NCDRC order seeking enhancement of compensation, as well as probing other instances of negligence.

“My fight is not over yet. After a judgment is out on this application I'll certainly file an appeal before the Supreme Court,” he says.

Comments

0 comment