views

Three days in a row – the last two days of August and the first day of September 2020 – newspapers in India carried perplexing front-page reports.

On 30 August, headlines prominently displayed the new set of Unlock India guidelines issued by the Centre. Equally prominently placed alongside was the news that the country broke the world record for the maximum number of new COVID-19 cases in a single day. With 78,761 new cases, India had broken the previous single day spread record of 77,200 COVID-positive cases logged by the United States on 17 July.

On 31 August, the front page headlines conveyed that India on the previous day, a Sunday, had achieved the dubious distinction of becoming the first country in the world to log more than 80,000 new COVID-19 cases in a single day.

On the third consecutive day, 1 September, the front pages screamed that India’s GDP — which was tottering even before the pandemic struck — had contracted by nearly 24 percent in the April-June quarter of FY 2020-21. The slump was said to be attributed to the prolonged countrywide lockdown imposed by the government as its first COVID-19 response.

The lockdown, which in hindsight, has done little to arrest the spread of infections, did freeze both investments and consumption across the core sectors and pushed up the unemployment rate. Since April, millions of workers have been laid-off and many small businesses shut overnight. Next to this story was the news detailing how the Unlock 4.0 guidelines of Maharashtra, the state that continues to contribute almost a quarter to the national tally of COVID-19 cases, had opened up most sectors, albeit with all mandatory preventive measures in place.

Nothing ‘august’ about August

India registered its first single-day 70,000-plus cases on 22 August. After a momentary decline over the next two days, the daily caseload jumped to 66,873 on 25 August. The subsequent four days consistently hit the 76,000-plus mark whereas on August 30, the country breached the 80,000-plus single day cases mark.

Incidentally, both the days when India breached the two unsavoury milestones of 70,000 and 80,000 daily case count fell on weekends, during which, the numbers had reliably dropped since the cases started spiralling in May. Lesser number of tests conducted over the weekends were considered to be contributing to the lower weekend figures. Earlier, the highest peak recorded on a Sunday was on 9 August, when 63,851 people tested positive.

The surge in the last week of August has also reversed some of India’s initial gains in terms of both the day-to-day growth of cases and fatalities. The growth rate of the number of cases reached 13.1 percent, nearly thrice than the average of 4.7 percent registered in the previous week. The highest earlier weekly peak of 10.9 percent was recorded during 3-9 August. The fatality rate also grew to nearly 4 percent, more than double of the 1.7 percent logged in the previous week.

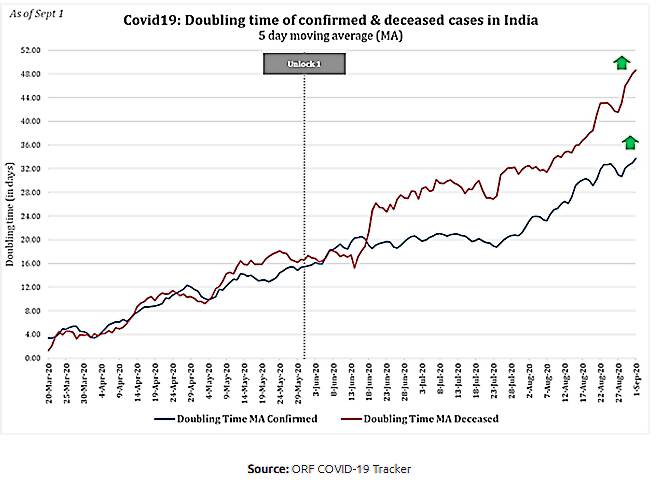

Despite the steep increase of cases, there was a silver lining around the dark COVID clouds in August. India successfully ramped up testing to ensure, on a five-day rolling average, a sharp rise in both – the doubling time for the growth of cases as well as deaths. From around a 24-day doubling rate of cases at the start of the month, the rate increased to around 33 days on 31 August. Likewise, the doubling rate of deaths also increased from around 30 days in early August to over 50 days by the month end. In early June, when the Unlock 1.0 was announced, the doubling rate of cases and deaths was at 15 and 17 days respectively.

This increase in the doubling rate can be attributed to the increased testing, which breached the 10 million tests per day mark towards August end. According to the Union Health Ministry, the exponential jump in the testing capacity and number of tests drove the tests per million to 30,000-plus. Increased testing also reduced the positivity rate (share of confirmed COVID-19 positive cases among all tests conducted) from nearly 12 percent on 25 July to marginally less than 8 percent on 31 August on a 7-day rolling average.

Balancing lives and livelihoods: India walks the tightrope

The surge was a foregone conclusion ever since the gradual lockdown relaxations were introduced. With the kind of the impact that the lockdown had on the economy, the unlocking too, wasn’t too hard to predict. However, given the increased fury with which the pandemic has spread, one is still quite unsure of when the peak will set in, let alone how long will it take to flatten the curve.

India’s CFR (case fatality rate) of 1.8 percent, which is well below the world average of 3.4 percent, as well as the country’s low positivity rate by and large seems to have given an impression that the ease on movement and businesses means that the country is out of the woods. Millions who were locked up indoors for months are convinced that the novel coronavirus is not all that dangerous as it was earlier believed to be and certainly not as deadly.

The way large crowds have thronged public places with little regard for face masks and social distancing norms and the pre-lockdown congestion on roads in India’s cities making a comeback prove that, for most, the pandemic is all but over. Such complexity was also reflected in the comments made by the municipal commissioner of Mumbai in mid-July. Citing the ramped-up testing facilities and the ‘R’ rate (rate of healthy people getting infected by a COVID-19 patient) being 1.1, he said that “technically” the pandemic was as good as over.

Cities such as Mumbai have done a commendable job in ensuring that the outbreak doesn’t run riot. They are therefore well-advised to learn from Auckland and South Korea, which despite having negligible population densities and a high degree of civic discipline, were recently forced to re-impose lockdowns as the virus struck back after it was claimed to have been defeated.

Incidentally, the spread of the pandemic in India is in line with the study predictions made by the Indian Institute of Science in mid-April. In a worst-case scenario, it concluded, India would record 3.5 million cases by August end. India has fared a bit worse, logging nearly 3.7 million cases as on 31 August. The peak, according to the worst-case scenario prediction, would set in only in March 2021. Another study, initially attributed to the ICMR which later distanced itself from the same, had claimed that the contagion will peak in the country by mid-November leading to a shortage of critical care equipment including isolation beds, ICUs and ventilators.

Indeed, the way things are going, the rural areas that already suffer from poor health infrastructure stand exposed to a much higher degree of risk. More than 55 percent of the cases during the surge in August came from 584 districts classified as “mostly rural” or “entirely rural”. Another 16 percent came from ‘rurban’ areas. To put this into context, “entire urban” areas contributed to 64 percent of India’s total cases in April. Dr T Jacob John, professor emeritus at Christian Medical College, Vellore, has surmised the governments in Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai – despite the initial spread like wildfire, brought the contagion under relative control thanks to the available health resources. “What we are likely to see in villages will not be like this — it will be slow- and long-burning fire … much harder to contain,” he warned, explaining how villages are “disadvantaged because of their inadequate health systems”.

Unlocking India: A necessary evil to be handled with caution

With a sure shot vaccine yet to be discovered and then made available to 1.3 billion Indians still an uncertain time away, the virus seems set to run its course in the country. The economic devastation caused by the lockdown has to be stopped by all means.

The onus is firmly on each individual to adhere to all the precautions and safety norms. From September, as the Unlock 4.0 sets in, the war against COVID-19 is literally an ‘all for one and one for all’ effort. At the same time, the government has to announce a slew of additional measures to boost the economy that is staring down a black hole. Unless targeted fiscal injections are not administered urgently, the “green shoots” are at a risk of withering away.

Disclaimer: Dhaval Desai is senior fellow and Vice President at Observer Research Foundation, Mumbai. View(s) expressed by the author are personal.

This article first appeared in ORF

Comments

0 comment