views

Prof Jagdev Singh, the principal investigator of the Aditya-L1 team during its early phase, has many reasons to smile today. “Twenty years ago, sending a spacecraft to the sun was considered ‘Mission Impossible’ but after years of convincing as well as numerous scientific debates and persuasion, it has become ‘Mission Possible’ today,” he said.

Riding on the success of Chandrayaan-3, India has now set its sights on the sun as the first solar mission Aditya-L1 lifts off at 11.50 am from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in Sriharikota on September 2 (Saturday). The prestigious mission has a special link to Chandrayaan-1, as it will be able to help scientists understand what caused the premature end of India’s first moon mission, which was triggered in part, by solar radiation.

Aditya, the Sanskrit word for the sun, will observe the solar corona from a remote location at the Lagrange point or L1 point, which is about 1.5 million km from Earth, and will take 120 days to reach it.

‘Dream come true’

“It was a dream to begin with when we first proposed the project, but today it has become a reality because of the hard work of the team over the years,” said Jagdev Singh. He explained how it was no simple task as they had to work hard to convince the management why it was important to send a satellite to study the sun.

“When you need funding to conduct such a complex programme, the first is to convince the management about the scientific reasons and then a feasibility study is the next stage. A lot of scientists and engineers looked into the feasibility study, though there was a small hitch at the beginning,” he said.

Questions were raised that when you can observe and learn about the sun from the Earth, what was the real need to have a space programme to study the sun alone? But scientists at Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA) said the management was suitably convinced.

“Today, you can see how we are heading towards the sun,” said the now retired scientist from IIA, but with excitement as he is witnessing two decades of work by scientists at IIA and ISRO “seeing the light of day”.

ISRO said a satellite placed in the halo orbit around the L1 point has the major advantage of continuously viewing the sun without any occultation or eclipses. This will provide a greater advantage of observing solar activity and its effect on space weather in real-time, said India’s space agency.

Scientists at IIA said in the early 2000s when the sun mission was proposed, they were looking for an initial coronagraph and possible observations of the solar corona using indigenous space-based telescopes. It was initially envisaged as a small 400 kg, low earth orbit (800 km) satellite with a coronagraph to study the corona.

The sun mission began to take shape in 2008 when Aditya was conceptualised in January that year with the advisory committee for space research giving the green signal to it.

From mobile phones, medical gadgets to cars: How space missions help in technology

There is a lot that can be gained from this mission. Today, every person – from a rickshaw puller to a person running their own business – all use mobile phones. This has been made available because of space research and technology. Decades of research involved in sending a rocket or satellite to space involves building lightweight, less volume, sturdy and tamper-proof material.

“The byproducts of building this are many. A lot of technology used in a car is based on space technology. Take for example a disabled person, until a decade ago they were using heavy gears or support to walk around. Today, these gadgets have become lightweight. This is because of the byproduct of space technology that has contributed to building apparatus that are light yet sturdy, just like our satellites,” Singh said.

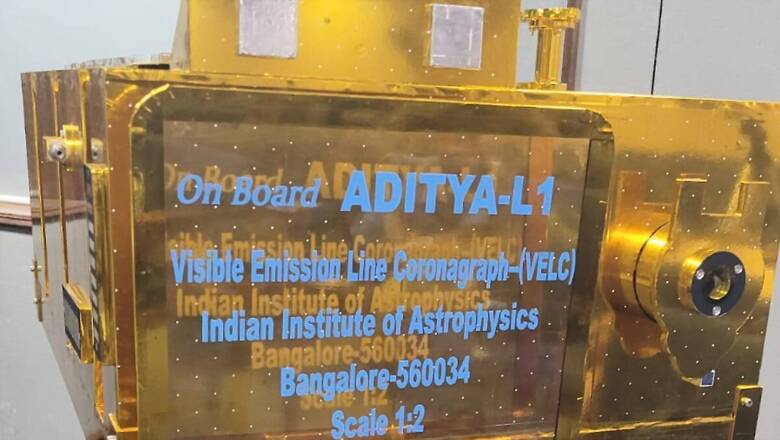

The prototype of Aditya-L1 at IIA reflects the intense research and years of experimentation and pressure tests conducted on the spacecraft, until it took its final shape. Scientists will be able to analyse and retrieve data about the sun and the coronasphere when there is an eclipse.

‘Permanent observation camp near the sun’

Dr Nagabhushana of the IIA said an eclipse is an event taking place within a fraction of time and, during this, scientists would run to a location carrying their telescope and equipment, camp there for hours and days to get a glimpse and try to get maximum information in a short time.

“Solar physicists and space researchers have to set up a camp to observe a phenomenon that lasts a few minutes. With Aditya-L1, it is like setting up a permanent camp near the sun for solar physicists in India who want to observe the corona and its dynamics from here,” he said.

The corona has piqued the interest of many: the temperature at the sun’s core is 15 million Kelvin; the outer atmosphere, which we see, is about 6,000 Kelvin; and once the rays reach the corona, it becomes a couple of million Kelvin. So, people are interested in studying the sun’s temperature and what causes its increase, said IIA scientists.

“To study the corona, you need to block the disc light, which is what happens in a natural solar eclipse. Instead of waiting for such an event, we are now presented with an opportunity that helps us gather data from close quarters about coronal mass ejections (CME) and the source for the coronal mass heating using the VELC instrument (the primary payload on Aditya-L1),” said Dr. Muthu Priya, Aditya-L1 project scientist and operations manager for VELC, or visible emission line coronagraph.

Nagabhushan said the IIA’s indigenously built VELC, which is one of the most important payloads onboard the Aditya-L1, has undergone a thorough testing to ensure it withstands the trip to the sun’s orbit, survives the launch load, friction while it is orbiting, and withstands any sun flares or thermal escalations ensuring the instruments are intact.

Bringing the sun into a laboratory on Earth

All eyes will be on the sun on Saturday, but IIA scientists are also hoping that they can ignite as much excitement among children during this event. Niruj Mohan Ramanujam, IIA’s head of science communication, public outreach and education, finds such space missions a perfect opportunity for children to learn, appreciate and be encouraged towards astronomy.

Ramanujam said the sun is ever present and we take it for granted as well while even looking out for it on a gloomy day or after an eclipse. “It is the closest star to the Earth. It is not any star, but only if we understand the sun will we be able to understand other stars and its proximity helps us observe and investigate it more closely. Just like the Big Bang and the Black Hole, the sun is also as fascinating,” he said.

Scientists over centuries have been fascinated that nuclear fusion is taking place on the sun’s surface and photons are emitted from its core due to nuclear fission. This takes thousands of years to reach the surface but just eight minutes to reach the Earth.

“The atmosphere of the sun is much hotter than its surface; these are matters that are not well known but would interest younger students. It is important that we use the sun in our education much more and find practical ways of teaching about it to students. India leads in teaching about experiments conducted by students at almost no cost, called ‘daytime astronomy’. Using the sun, measuring its shadow and an object, calculate a lot of things about the universe itself. That in some sense brings the sun close to us or as we call it ‘suraj zameer paar’,” the scientist said.

Scientists are hoping to bring the sun into people’s homes and classrooms with the help of Aditya-L1.

Comments

0 comment