views

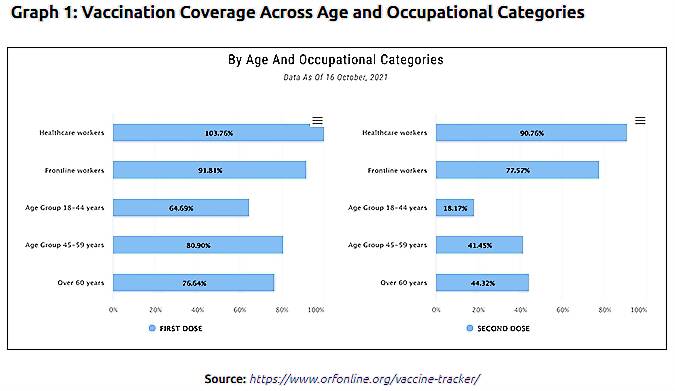

Latest available data (as of October 16) indicates that India has administered 699.6 million first doses and 286.3 million second doses of COVID-19 vaccines to its adult population. The coverage is markedly higher amongst the 45+ population (Graph 1), with about 80 per cent within the age group having received at least one dose, and more than 40 per cent fully vaccinated. The Government of India’s goal is to vaccinate all adults against COVID-19 by December 31, 2021, and therefore, the pace of vaccination in the last quarter is of importance.

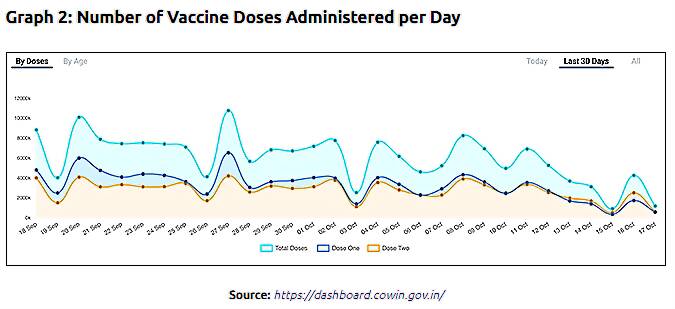

The numbers in the recent weeks have been disappointing. Instead of accelerating to the required average daily vaccination rate of more than 11 million per day (required on October 1), the number of daily vaccine doses administered has shown stagnation and, indeed, a decline. From 8.2 million doses on October 8, the daily numbers have declined considerably, taking down the seven-day moving average from 6 million per day to 3.9 million per day on October 18. While the festivities across the country may be part of the explanation, there are clearly other factors at play, which may undermine the December 31 target that the Government of India has set for itself. This, therefore, needs to be explored in-depth; the possible reasons behind such a surprising slowdown in the vaccine uptake uncovered and remedial measures instituted need to be examined.

ALSO READ | As India Crosses 1 Billion Covid Jabs, Overcoming Rural-Urban Divide is the Real Success Story

Is the Decline in Numbers Due to Supply Constraints?

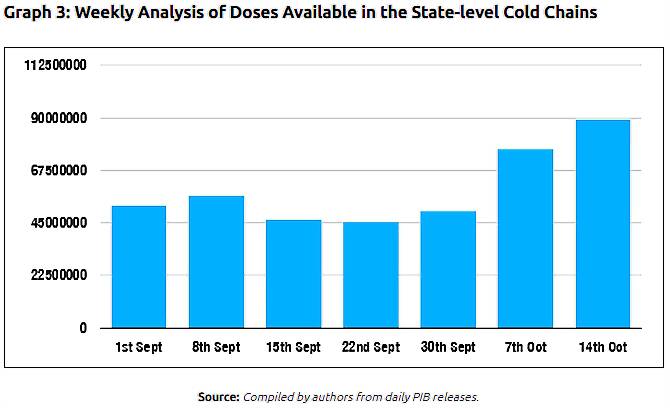

While it is a legitimate question to ask, given the history of delays in capacity ramp up for different vaccines in India, this does not seem to be the driver of the slowdown. A look at the unutilised vaccine doses still available within the vaccine cold-chain—the difference between doses supplied to the states and those administered—strongly points to this. A weekly analysis of the available doses with the states (Graph 3) shows that there is substantial build-up of vaccine inventory at the state level. During a month between 15 September and 14 October, the doses available with states almost doubled from 46.3 million to 88.9 million. The data made available on October 18 indicates that there are currently 107.2 million doses awaiting to be administered in the states and union territories. This trend indicates one possibility: There is a strong tapering off of demand for COVID-19 vaccines.

Earlier this year, at the beginning of the vaccination drive, when both number of cases and deaths were low, there was a distinct lack of demand for vaccines, which shot up only with the surge in cases. However, with more than 70 per cent adult Indians already vaccinated with one dose, this may not be the major contributor. Demand may be flagging as many Indian states may have already reached almost all of the “willing” adults with one dose at least. Perhaps the undecided and the ‘vaccine hesitants’ are now the ones left and the tapering of numbers could be an outcome of this.

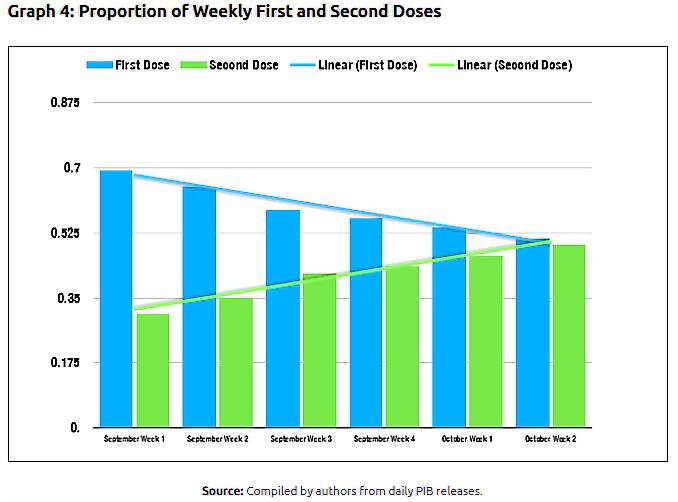

Weekly vaccination data disaggregated by doses from September 1 onwards (Graph 4) underlines this possibility. As a proportion of the weekly doses, first doses are on a clear decline over the last six weeks. In the first week of September, first doses constituted almost 70 per cent of total vaccinations, but in the second week of October, it was just over 50 per cent. This could only mean that the vaccination drive in many parts of the country may have already reached the easy-to-reach population. Vaccinating all of the remaining 30 per cent or so of adult Indians will require additional efforts from the government, local leaders, and civil society.

Towards Herd Immunity: Last Mile Will be Hardest

In the third week of October so far, second doses have outstripped first doses by a big margin. Between October 14 and 18, of the total 14.8 million doses administered in India, only 6.3 million were (42 per cent) first doses, showing clearly that the second doses are now driving the overall numbers. With the offer of free vaccine for all adult citizens, the Government of India has removed financial access barriers from the picture.

However, for many sub-populations, physical access to vaccination centres may be difficult for a range of reasons. Vaccine hesitancy will also be a problem in a small but significant proportion of the population. To overcome these, the government must run the vaccination drive in surgical mode, focusing on communication, community engagement and hard-to-reach populations. Many states are already deploying mobile vaccination teams to take vaccines to the people in the margins, with success.

EXCLUSIVE | Billion on the Board: Six People Who Steered World’s Largest Vaccination Drive

At the same time, the Centre and state governments must now focus on district-level champions to win the battle of perception, and to take vaccines to the constituency that is the most difficult to reach—those hesitant to take vaccines. That many of them may be highly vulnerable to COVID-19 due to age or comorbidities makes such an initiative an ethical imperative.

In short, first doses are drying up across the country, which could be either due to access-related issues or vaccine hesitancy. India needs district level mop-up operations. The vaccination drive’s initial phases leveraged technology in a big way, but the last mile needs to leverage communities and personalities alongside technology. Many countries are finding ways to nudge and even push the citizenry towards COVID-19 vaccination, focusing on employers and travellers. Canada, for example, is planning to place unvaccinated government employees on unpaid leave and has also made COVID-19 shots mandatory for air, train, and ship passengers.

Throughout the pandemic, India has had one of the highest proportions of population willing to be vaccinated when compared with other countries. For the same reason, a smart communication campaign should do in India what vaccine mandates are failing to do in many other countries. With 100 crore vaccine doses administered, and a robust information backbone tracking tests, vaccinations and cases, it should not be difficult to convince those still doubtful about the efficacy or the safety of vaccines. Popular personalities, political and religious leaders, and civil society organisations should be engaged actively to take evidence-based messaging to the district level, particularly in those areas where vaccine uptake remains low.

Given the deceleration in vaccination we observed over the last few days, it is easy for India to be in a situation where vaccine doses to meet the December 31 target are available but demand becomes the binding constraint.

This article was first published on ORF.

Samir Saran is President, Observer Research Foundation. Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at ORF. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest News , Breaking News and IPL 2022 Live Updates here.

Comments

0 comment