views

We’re at the halfway stage of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. While we won’t know the verdict of the people till June 4, many “political experts” mostly from the anti-Modi tribe have declared that the NDA is in trouble. That the 2024 Lok Sabha election will be a near repeat of the 2004 Lok Sabha election. In that election, the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led NDA was widely tipped to win comfortably. The NDA was riding on the “India Shining” slogan and a fractured Opposition was not expected to pose a challenge. But in the end, the NDA lost.

The “political experts” say they’re confident because there are “2004-like factors” at play in 2024. First, a lower voter turnout than in 2019. This they say was also true of the 2004 election when fewer electors voted compared to 1999. Second, the existence of ground-level anti-incumbency despite the BJP having denied tickets to a fourth of its sitting MPs. And the absence of any one leader projected against PM Modi, which prevents the election from assuming the character of a presidential-style face-off.

But are these “2004-like factors” playing a decisive role as these “political experts” have predicted? Has the election turned?

Here are some fact-based arguments that will establish that 2024 isn’t 2004 and that those predicting gloom for the BJP might end up with eggs on their faces.

Low Voter Turnout Isn’t A Vote Against BJP

There is no conclusive correlation between voter turnout and poll outcomes. Over the years, the data shows that incumbent governments have returned when the turnout has fallen, and incumbents have been ousted when the turnout has risen. Nevertheless, a detailed study on voter participation in the 2004, 2009, and 2014 general elections by Dr Prannoy Roy and Dorab Sopariwala concluded that the BJP consistently won in constituencies where the turnout had dropped. This, the study concluded, was because unlike other parties the BJP has a strong cadre-level organisation of booth workers and “panna pramukhs” that are experts in getting the core vote out. In a low turnout scenario, the BJP’s strong booth-level ground game will ensure that at the very least its ideologically committed voters will turn up to vote. The same can’t be said about opposition parties, particularly the Congress, which have witnessed considerable booth-level atrophy.

BJP Has UP & Bihar In The North

In 2019, the BJP won 224 seats by receiving 50% or more votes. Most of these stronghold seats were in the North, some in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar despite the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party stitching together an improbable alliance. If the Opposition is to wrest power from the NDA it will have to spring surprises in these two states. Remember no government has ever captured power in Delhi without a presence in these two states.

A big reason for the viability of the UPA or even the UF governments in the 1990s was that they had support from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. In 2004, still electorally vigorous, caste-based parties like the SP, BSP, and RJD had pushed the BJP-led NDA into a corner. The NDA for instance had a claim over just 22 out of a maximum of 120 Lok Sabha seats from these two states.

But the NDA has come a long way since 2004. In 2019, the NDA Was sitting pretty on a nearly 50 per cent vote share. The Opposition will have to bridge a massive gap between itself and the BJP if it is going to make a comeback in this election. Only a very partisan “political analyst” will risk his reputation to predict a BJP rout in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

The BJP’s Ram Baan

The NDA’s dominance in the North, where it bagged 210 out of 244 seats is all but ensured. While the BJP is experiencing anti-incumbency pressures it has offset them by mobilising its base through its messaging on Ram and the mandir. The timing of the Ram mandir inauguration and the carefully curated ceremony aimed at including a panoply of castes was a calibrated exercise to shore up the BJP’s big caste coalition.

The Ram Mandir gambit, if it could be called that, has helped the BJP neutralise the Opposition’s bid to undercut the party’s rainbow caste coalition by floating the “caste census” balloon.

The ‘Modi Versus Khichdi’ Isn’t An Option

The Opposition is convinced that it has succeeded in avoiding turning the election into a presidential-style contest by not projecting a leader against Modi. But adopting such a strategy also hands the BJP a vital advantage. It allows it to market stable leadership under a decisive Modi as its unique selling point. Indian voters are today more aware of the chaotic impact of global strife in an interconnected world upon their daily lives. With wars, testy neighbours and a pandemic having driven home the point, voters are looking for security via stability at the national level. Especially the narrative setting aspirational middle class. The prospect of a fractious coalition with competing interests and a varying vision for governance acquiring power may not appeal. This antipathy towards instability is borne out even at the assembly level where a whopping 78% of the mandates in the last few years have been decisive. Of the remaining 22% of the verdicts, 80% have been in favour of a tested pre-poll alliance.

The Southern Switch

The BJP-led NDA has set itself an ambitious target in the South. It hopes to capture 40 seats. The more optimistic saffron-istas are dreaming about 50. The BJP may end up short. But because it only won 29 out of 129 seats in the South in 2019 it believes it has room to grow. In Karnataka, the BJP maxed out in 2019 and may yet concede a few seats but this will only happen if the Congress can dramatically swing votes. To put the challenge for the Opposition in perspective, the BJP’s average victory margin across seats in Karnataka was 1.75 lakh votes. Dramatic swings are rare. But they do happen. In 2019 for instance, the BJP’s vote share in Bengal went up to 40% from a mere 17% in 2014. But 2019 was thought to be a Modi wave election. There may not be a Modi wave but there certainly isn’t a discernible anti-Modi wave either. Modi remains very popular in 2024.

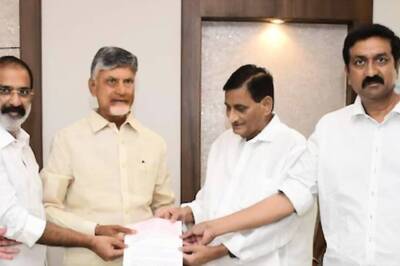

Losses in Karnataka may be offset in Telangana and Andhra.

In Telangana, if even 10% of the approximately 40% BRS votes were to shift to the BJP, the party would bag 5 seats.

In Andhra, the NDA is a three-party bloc that is expected to give the Jagan Reddy-led YSRCP a run for its money. Here, the Congress is a non-starter, so the NDA hopes to be the beneficiary of any anti-incumbency. NDA baiters will also note that the UPA was able to sustain itself between 2004 and 2014 largely because of its tremendous showing in unified Andhra. In 2004, UPA had 29 seats and its ally the communist parties 2 out of a total of 40 seats. And given that we haven’t even analysed Kerala and Tamil Nadu, it is highly improbable that the NDA’s tally will dip below its 2019 showing in the South. With the North largely in the bag and the South holding up, the NDA is unlikely to stumble at the final hurdle.

In the end analysis, the five factors listed here could be some of the more compelling reasons why Modi’s NDA in 2024 won’t go the way of Vajpayee’s NDA in 2004.

Comments

0 comment