views

As Indians, we are extremely proud of our culture and tradition and we will go to any lengths to preserve them. This was proved true yet again, when thousands of people gathered around the Marina Beach in Chennai last year, all with the sole aim of “saving” their centuries-old tradition of Jallikattu.

Pongal in Tamil Nadu last year was nothing like the usual as January 2017 saw the birth of a leaderless movement in Tamil Nadu, where people took to the streets to save Jallikattu, a bull-taming sport, traditionally organised during this festival.

What is widely acknowledged as a 'cruel' sport by the rest of India, for the Tamils, Jallikattu is more about culture and pride.

A rural sport, Jallikattu grabbed national attention only after last year's massive protests. However, little do people know about the actual purpose of the sport and its cultural significance.

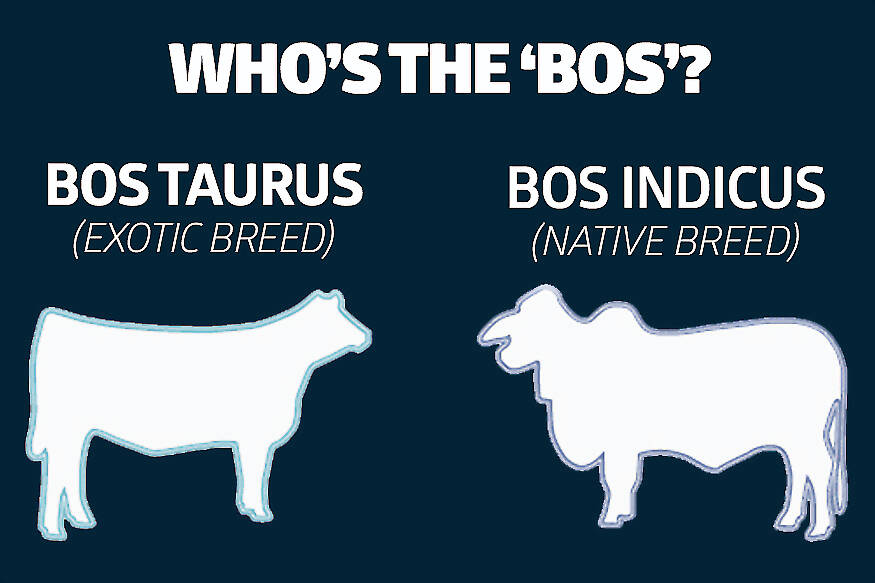

"Jallikattu is more of a scientific practice than a sport," says Karthikeya Senapathy, one of the most prominent voices on the issue. He claims that Jallikattu helps in identifying superior bull breeds for mating and gene preservation. Those bulls that win the sport are selected for mating, while the other remaining bulls are used for farming activities.

In 2014, when the Supreme Court imposed a ban on the sport, prices of Kangeyam and Pulikulam breed of bulls, which are traditionally used for the sport, plummeted. As a result, people lost the incentive to rear these breeds. This, coupled with the addition of tractors and other farming machinery, added to the distress of bull owners.

A Jallikattu event from January 2017. (Image courtesy: Balakumar Somu)

In 2016, the Centre's notification allowing the bull-taming sport was challenged in the Supreme Court by PETA and a Bengaluru-based NGO. The Centre, in January 2017, filed a plea in the Supreme Court seeking to withdraw its January 6, 2016, notification issued by the Ministry of Environment and Forest.

One of the main players that instrumented the ban on Jallikattu was the People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). The animal rights group invoked the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (1960), to say that bulls are subjected to torture with the sport.

"Those who have no knowledge of the sport speak of it as cruelty. They have no touch with ground realities and hence don't understand how we conduct Jallikattu," said Senapathy. He said that PETA and other animal rights activists’ move to protect the cattle breed, has in fact made the indigenous breeds and their future extremely vulnerable.

The indigenous breeds of bull require low maintenance and are perfectly suited to the local climatic conditions. The exotic breeds are prone to serious diseases and rearing them is a highly expensive affair, claims Senapathy.

Following the ban in 2017, farmers across Tamil Nadu have had to shift from the native breed to the genetically modified ones to look for short-term gains with more milk. The Jersey and Holstein Friesian cows produce over 12 litres milk/day, while the indigenous breed produces a little over 3 litres.

Therein lies the science behind Jallikattu. There are two varieties of milk produced by the two breeds of cattle, A1 milk (produced by exotic breeds) and A2 milk (produced by the indigenous breeds). Experts say A1 milk contains an unwanted protein component called BCM-7, which is said to cause Type 1 diabetes apart from having other negative effects on health. However, this has been a matter of debate and has not been proven well.

“It’s not just about the Kangeyam or Pulikulam breeds in Tamil Nadu. Karnataka’s Kambala, other bull races in Andhra Pradesh and similar events in Punjab, Haryana, and other places with good indigenous breeds have also been targeted," says P Rajashekar, member of the Jallikattu Padhukappu Peravai (Jallikattu Protection Forum).

Supporters of Jallikattu disregard the claims of animal cruelty and say that the videos that went viral and were used as evidence to cite cruelty are either dated, i.e., shot prior to when rules were framed for Jallikattu or are doctored. Their primary stand has been that the ban is a ploy by PETA and other animal welfare activists to harm the Tamil culture and wipe out indigenous breeds.

On the contrary, PETA and other animal welfare activists claim that Jallikattu is inherently a cruel sport and no amount of regulations can prevent harm to bulls or humans involved.

"There is no middle ground here. There’s a lack of consent from the two parties involved in the sport. There is no consent from the bull," said Nikunj Sharma, Head of Public Policy, PETA India.

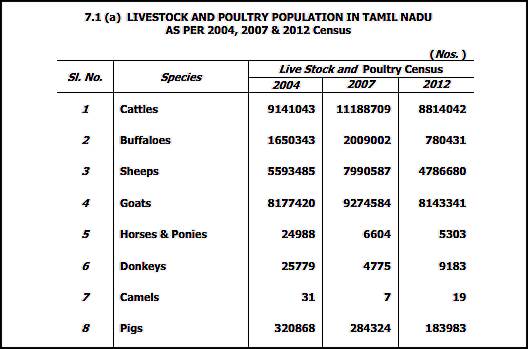

PETA has also rubbished the claims of a hidden agenda to wipe out the indigenous breeds. They say that the number of indigenous breeds had declined even before 2014, when the ban was first imposed. The last Tamil Nadu Cattle Census (2012) shows a considerable drop in the number of cattle between 2007 and 2012.

However, it has to be noted here that the numbers have been declining partly because of the introduction of tractors and other machinery, all of which took away the incentive for farmers to raise a bull.

"Jallikattu is the only reason for farmers to raise these bulls. If you take that away, it will be like the last nail in the coffin," said Balakumar Somu, Founder of ARHAM (Activists for Righteous Harmony of Animals Movement) Trust.

"We have so many accidents in cricket, football, or other sports where players die. We don't ban those sports, we simply impose regulations," he said. The supporters say that for them Jallikattu is like playing with their ‘child’, a way to show their love to a member of their family.

The underlying message behind last year's agitation is the importance and need to protect the native breed. But will events like Jallikattu serve the purpose? Maybe not.

There is need for a proper policy framework backed by the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity.

The Animal Welfare Board of India needs to educate people about the importance of conserving native cattle. Organisations such as PETA, who are "concerned" about the safety of bulls, need to visit these villages and educate people on how to handle bulls. “They get funding in the name of animal welfare. So why are they not coming onto the field and educating people? They can’t just sit inside AC rooms and ban everything,” said Balakumar Somu.

Tamil Nadu is arguably at its worst ever phase with regards to its agricultural sector. The only hope the rural Tamils have is to survive with what they are left with – their cattle. You take that away and you take away a very critical means of their livelihood. Equally important is to ensure genetic diversity of cattle. If we don’t take some bold steps, 10 years down the line, all that we will be left with are the Jerseys and Friesians.

Comments

0 comment