views

India slipped 28 places from 112 to 140 in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2021. The pandemic year resulted in India’s gender gap closing window widening by 4.3 percentage points. The key and persistent characteristic of the increasing gender gap is the plunge in economic opportunities for Indian women leading to their declining participation in the formal workforce.

As per data from the World Bank, female labour force participation rate (FLPR) in India decreased from 30.27 per cent in 1990 to 20.8 per cent in 2019. Amongst the early explanations for this fall in FLPR was that women could have left formal workforce to attain higher education. While to some extent, this is true; as per the findings from All India Survey of Higher Education, Female Gross Enrolment Ratio (FGER) in higher education increased from 44 per cent to 49 per cent from 2011-12 to 2018-19. However, the increased number of women enrolled in higher education still do not account for the ‘missing women in formal work’ in India. The question thus arises—what are women doing with their time?

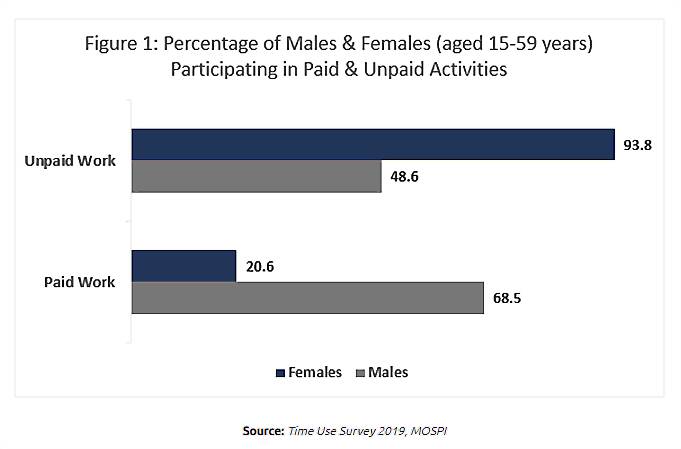

According to the findings of India’s first ever Time Use Survey, only 20.6 per cent of women aged between 15-59 years were engaged in paid work as compared to 70 per cent men in the same age bracket. While this enormous gap is reflective of Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) estimates, the greater variation comes in unpaid work. As compared to 94 per cent of women, only 49 per cent of all men surveyed aged 15-59 years participated in unpaid work (Figure 1).

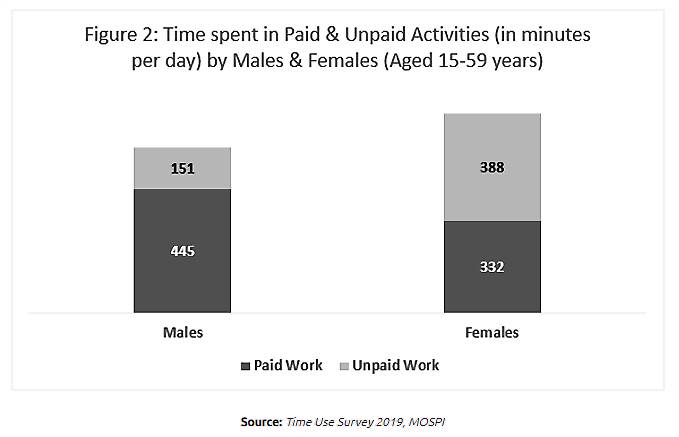

While the percentage differential for unpaid work is exceptionally wide, there is a further discrepancy in the hours spent engaging in this unpaid work. An Indian woman, on average, spends over 21 per cent of her time on unpaid work, especially, care-giving activities and domestic chores like cleaning and cooking. While an Indian man, on average, spends just five percent of his time on such work.

Thus, as evident in figure 2, women spend more time performing unpaid labour than paid labour in a given day. Additionally, if one were to count, both these work categorisations based on minutes per day contributed, women clearly outperform men. Indeed, several estimates report that if women’s work were recognized correctly, FLPR would be 81.6 per cent, as compared to Male Labour Force Participation Rate (MLFR) of 76.7 percent.

However, not only does the formal economy not recognise the unpaid care work performed by women, but the sexual division of labour, emerging out of patriarchy, also dictates women’s role in society and compels them to believe that women are primarily responsible to perform unpaid care duties at home.

The performance of this unpaid care work allows family structures to not pay for these essential activities formally. Thus, unpaid care work provides a substantial subsidy to formal economy and despite being vital for any economy to survive and thrive, unpaid care work is not recognised as ‘work’. This phenomenon is referred to as invisibilisation of women’s work. While the formal economy is made to run on the backs of women, the extreme burden of carrying out unpaid care work, however, leads to women’s time poverty.

In its most trivial sense, time poverty means dearth of time available for entirely personal needs, like recreational and social activities. The diversity of unpaid tasks limits women’s time, agency, and, thereby, their ability to make choices. It keeps them from pursuing higher education, increasing their skill levels, attending to their own well-being and especially hinders their ability to pursue formal employment opportunities. Thus, time poverty emerging from the gendered responsibility of performing unpaid labour at home erects a major obstacle in women’s ability to contribute directly to formal paid work.

Time poverty is an even larger constraint for poorer women. While richer sectors of society could still outsource some care-giving activities; in the absence of public care infrastructure, it is impossible for poorer women to do so. This, thereby, closes the doors of formal work for them. In addition, not being able to undertake formal work further disallows these women to have a source of income, in turn, leaving them disempowered with even less agency.

For women, who despite these hurdles, somehow manage to pursue paid employment, the double burden of paid and unpaid work, referred to as the ‘double shift’, creates a deeper nexus of time poverty. Furthermore, the unreasonable acceptance of domestic work and caregiving as womanly duties, and no efforts of redistribution of this unpaid work, leads to sexist behaviours at formal workplace, largely indicative by the huge wage gap prevalent in our country. Indeed, the estimated earned income of women in India is only one-fifth of men’s earned income.

The case of ‘missing women in formal economy’ is especially urgent to address now, given the pandemic’s extreme detrimental effect on women’s social and economic well-being. With no substitutes for care available in the lockdown, women were drowned in caregiving duties. As per estimates, the pandemic increased the burden of unpaid work on women by 30 per cent.

Moreover, the pandemic unleashed a ‘shecession’ with women being forced out of formal workforce. A study reveals that four out of every 10 women who were working prior to the lockdown, lost their jobs during the lockdown. Thus, the issue of women’s time poverty, gendered pay gap, and declining FLPR is extremely important to address if India aims to achieve an inclusive, rapid, and all-round development of its economy. On estimating the monetary value of the unpaid work performed by women in a year, it accounts for 3.1 per cent of India’s GDP. This is, hence, an area worth capitalising on.

The way to enhance women’s economic empowerment is through not just explicitly increasing female employment opportunities, but also reducing the double shift burden women face. Hence, what is needed is adoption of 3Rs approach which involves ‘Recognising, Reducing, and Redistributing’ the unpaid care work done by women, in all areas of policymaking.

The best way to implement a system that allows adoption of 3Rs and facilitate women’s work is investment in public-sector care infrastructure. In the absence of public-sector care provisions and private-sector affordable care services, women are left to bear the burden of care activities, which inevitably pushes them out of the workforce. However, if alternative arrangements for childcare and household work were made available, women would find it much easier to come out of the time poverty they experience and pursue formal employment.

As per reports, public investment of just two per cent of India’s GDP in the care economy, could not only generate 11 million jobs for a country facing acute joblessness, but could also increase women’s economic and social welfare as they venture out into formal work. Thus, by adopting the 3Rs approach, not only can India tackle the root of declining FLPR while but also advance as a rapidly growing equal society.

This article was first published on ORF.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment