views

X

Research source

Deciding You Have Reason to Search

Check if you are a public or private school. Generally, students in private schools do not have the same federal constitutional rights as students in public schools. Accordingly, students are not protected from unreasonable searches and seizures. However, your state’s constitution (and other laws) can limit a private school’s ability to search students. You should be aware of those laws. Your state’s constitution and other laws also can provide greater protection to students in public schools. The federal U.S. constitution provides only a “floor” for constitutional rights which states cannot go below. However, your state can give students additional rights.

Identify why you are suspicious. Before you can search, you must have reasonable suspicion that the student has violated a school rule or the law. Take a moment to calmly reflect on what you know. Consider the following: The student’s history and school record. Has the student been caught committing the suspected offense before? The prevalence of the problem in school. The seriousness of the problem. Not every infraction necessarily requires a search. Your prior experience with the student. What information you know and whether it is reliable.

Assess the reliability of student tips. Often, a student will report that another student has broken school rules. You shouldn’t immediately believe the student. Instead, assess the student’s reliability based on the following: Did the student see the conduct with their own eyes? Or are they relying on secondhand reporting? A tip is more believable if the student witnessed the conduct. How reliable has the student been in the past? A student who has lied before is less believable. What is the relationship between the accused and the tipster? Are they rivals? Friends? If the students hate each other, you have reason to discount the tip.

Determine if your suspicion is “reasonable.” A reasonable suspicion isn’t a “hunch” or guess. You can’t think, “There’s just something wrong with this child.” If someone’s jacket looks weird, you can’t search it solely because of its appearance. Instead, reasonable suspicion should be based on reliable facts you can articulate to someone else. You should also be able to clearly articulate what law or school rule the student has violated. Talk about these issues with someone so that you can clarify in your own mind whether you have sufficient facts to perform a legal search.

Ask the student for consent. A student can consent to a search of their body or belongings. If they consent, you don’t need reasonable suspicion to conduct the search and they can’t sue you. However, your search cannot exceed the scope of consent. Tell the student what you want to search and ask if you have their permission. Make sure to have another person present to act as a witness. A student might give consent then claim later they never did. Having a witness protects against that. Ideally, you should get the student to sign a consent form. You cannot coerce or unduly influence the student in any way. Don’t threaten the student with suspension if they refuse. You also can’t interpret refusal to give consent as evidence supporting reasonable suspicion.

Plan a random search of the school. You don’t need reasonable suspicion if you intend to do a random search of the entire school. For example, you might want to randomly check whether students have weapons on them. Random searches can be effective as a deterrent: there’s a probability any student could be searched, so many will choose not to break the rules. However, the search must truly be random. You can’t call a search “random” when what you really intend to do is target one or more individual students. You can also perform searches of all students. For example, you can require all students to walk through a metal detector to get into the school. You can’t single out only certain students, however, unless you have reasonable suspicion.

Determine if contraband is in plain view. Students do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in contraband that is in plain view. For example, if a student opens their locker and a bag of marijuana falls out, then the marijuana is in plain view. It is also in plain view if the locker is open and you can see it as you walk by. Other examples include walking past a student’s car and seeing contraband on the seat or seeing students pass contraband. You can seize this contraband. The plain view doctrine doesn’t let you open up a student’s locker in the hope that something falls out or open up a student’s purse in the hopes that drugs are sitting on top of the makeup.

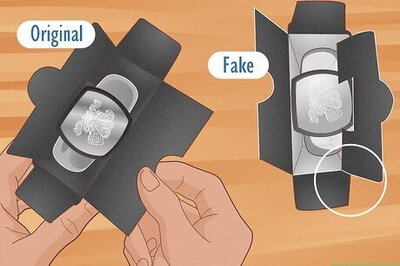

Identify if the property is school property. Depending on your state, students have lowered expectations of privacy in property that belongs to the school, such as desks, lockers, and school computers. In some states, students have no expectation and you can search the property whenever you want. You must clearly identify property as school property. For example, your student manual should describe the property as school property and you should exercise control over it. You also should not have students share lockers, which might confuse the student as to who owns the locker. If there’s a question whether the property belongs to the school or the student, don’t search it unless you have reasonable suspicion. For example, you can’t just decide that the lockers are school property because you want to search it. You must have given the student notice.

Conducting the Search

Determine the scope of your search. Your search must be reasonable based on the nature of the infraction. In particular, identify the illegal item you think the student has possession of. This will narrow down what you can search. For example, if you suspect a student has brought a handgun into school, don’t open small pockets on the student’s jacket—the gun cannot fit into that small space. Likewise, if you think a student has downloaded illegal material to their laptop, don’t start patting down their clothing. That search has nothing to do with the suspected infraction.

Search no more than necessary. Your search cannot be intrusive, even if you have reasonable suspicion that the student has broken a rule. Instead, you should search only as much as is necessary depending on the circumstances. For example, strip searches are highly intrusive. To protect yourself, you should only perform a strip search if the contraband is very dangerous, such as a weapon or dangerous drugs. It is unreasonable to strip search someone who might have stolen money or who might be carrying aspirin. The age and sex of the child also impacts the intrusiveness of the search. For example, a search of a teen by a teacher of the opposite sex can often be intrusive.

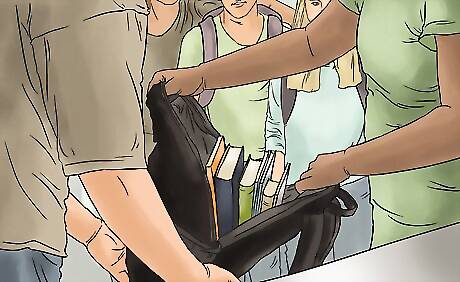

Don’t exceed the scope of a consensual search. A student can give you permission to search their belongings. However, you can’t exceed the scope of the permission granted. For example, if the student gave permission to look in their backpack, don’t start opening the pockets to their jacket. You don’t have consent to search the jacket. Should you want to search the student’s jacket, ask for permission. Otherwise, you can’t search unless you have reasonable suspicion.

Use same-sex searchers. Conduct searches in teams of two. There should be a witness to the search. If you are a male employee, you shouldn’t search a female student’s body. Female employees also shouldn’t search a male student. Instead, make sure that the person conducting the search and the witness are the same sex as the student. The purpose of this rule is to protect you from claims of impropriety. If you’re only searching a locker or bag, then the person searching can be the opposite sex. However, you always need a witness.

Minimize embarrassment to the student. Escort the student out of class and go to a private area to perform the search. Make sure the student has everything with them that you need to search, such as bags and jackets. Stay out of view of other people. The only people present should be the student, the searcher, and the witness. Search in a place where you will not be interrupted. You don’t want to unduly delay the search.

Continue the search even if you find contraband. Don’t stop as soon as you find a bag of weed or a knife. The student might have more hidden away, so continue with your search. Always remember that the scope of the search must be justified by the circumstances. It can be very easy to accidentally expand the scope of the search once you get started. For example, you might have a student take their bag to your office. As you search, you might think, “Since I have the student here, I might as well search her coat.” However, you can only search the coat if you have a reasonable suspicion that the coat has contraband hidden in it.

Seize illegal contraband. If you find illegal items, then seize them. Carefully document the item by writing down a description, as well as the date and time it was seized. Include the name of the person who found the item and the name of the witness. When you are finished, seal each item in an envelope and either store it in a locked location or immediately call law enforcement to pick it up. Also create a chain of custody where you write down the names of all the people you transferred the item to. Also remember to notify parents of a search. Although your state law might not absolutely require this step, it is a good one to take.

Create a legal school drug policy. It is not legal to request drug testing of all students. However, it is legal under the federal constitution to ask students to undergo drug testing in order to participate in extracurricular activities. You should work closely with your school district’s lawyer to craft a detailed policy that will be legal. For example, you’ll need to consider the following: The drugs you will test for. Who you will test. You can test all participants before the season starts and also perform random testing throughout the season. What actions you will take if a student fails the test. The purpose of a drug testing policy is to catch and remediate problems, not punish students.

Comments

0 comment