views

Writing a Flashback in Prose Fiction

Determine why you need a flashback. Flashbacks can be useful, but they aren’t always necessary to tell a clear and engaging story. Before writing a flashback, think about what exactly you are trying to accomplish and how it will serve your story. For example, you might use a flashback to: Provide information about a character’s past that sheds light on their current actions, beliefs, or attitudes (such as revealing a past trauma or other formative experience in the character’s life). Give context or information about events that are happening during the present plot (such as an important clue to a mystery plot). Helping the world of the story feel deeper and richer (e.g., providing historical background for the setting of a fantasy story).

Place the flashback at a point where it won’t disrupt the flow of the story. Timing is an important part of writing an effective flashback. Try to place the flashback at a point in the story where the audience already has a sense of who the characters are and what the story is about. Don’t use a flashback during a scene where it will slow down the action. If you feel you must provide past information in order for the start of the story to make sense, simply begin the story at a past point in time and then skip forward to the main timeframe. Avoid using flashbacks during intense action scenes, since they can slow down the action and make it feel choppy.

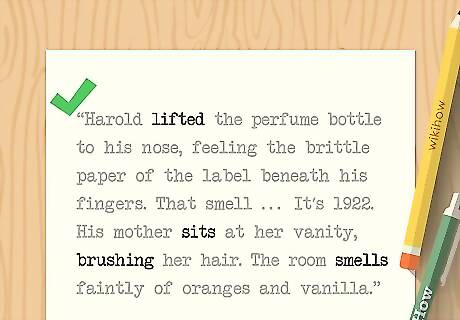

Choose a consistent tense for the flashback. Flashbacks are often distinguished from the action of the main timeframe by being written in a different tense. Whatever tense you choose, make sure you apply it consistently throughout the flashback, or the reader will be confused. Don’t feel confined to writing your flashback in the past tense. If your main timeframe is written in the simple past, you might make the flashback feel more immediate and engaging by putting it in the present tense. For example: “Harold lifted the perfume bottle to his nose, feeling the brittle paper of the label beneath his fingers. That smell . . . It’s 1922. His mother sits at her vanity, brushing her hair. The room smells faintly of oranges and vanilla.”

Select an event for your flashback to focus on. In general, it’s best for flashbacks to be short and simple. Pick a single event or moment that provides whatever key information you want your flashback to convey. You could potentially have a flashback that takes place over a longer period of time (e.g., a few days), but it is still important to keep it focused and limited. Maybe you want to show how your character came to pursue their current career. Instead of giving a lengthy account of how their interests developed, show a single moment that inspired them. For example, if your character is an archaeologist, your flashback might describe them visiting a museum as a child and being awed and captivated by a particular artifact.

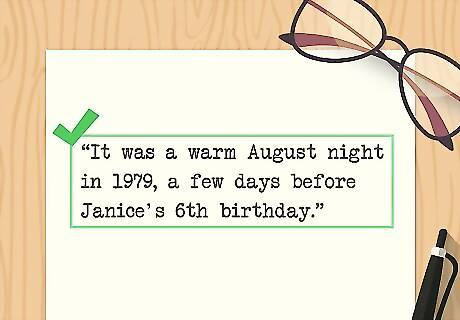

Define the timeframe of your flashback. Your flashback will feel most real and immersive if you know exactly when it takes place. You don’t necessarily have to tell your reader when it is happening down to the date and time, but it will help you as a writer if you know these details. For example, instead of setting a flashback at some vague point during your character’s childhood, you might set it in August, a few days before their 6th birthday. It can also help to think about how specific details might differ between your flashback and the present day. Do your characters look, act, or speak differently? How has the setting changed? Is the cultural context different?

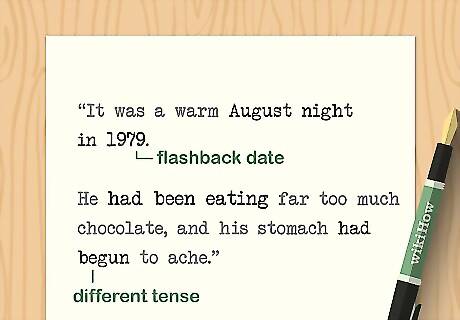

Use textual cues to clarify where the flashback begins and ends. Your flashback will need to be distinguished in some way from the main timeframe of the narrative. There are many different ways to do this. One of the easiest methods is to indicate in the text that you have changed to a different timeframe. For example, you might: Specify the date of your flashback (e.g., “It was a warm August night in 1979.”) Set the flashback apart by using a different tense from the main narrative (e.g., past perfect instead of simple past—“He had been eating far too much chocolate, and his stomach had begun to ache.”) State overtly in the text that your point-of-view character is remembering a past event. (E.g., “Harold was suddenly gripped by a memory—he saw his father silhouetted in the doorway, holding the cat in his arms.”)

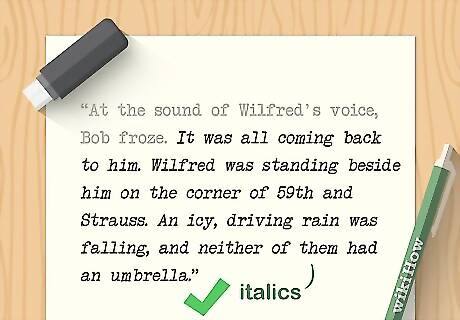

Set your flashback apart with different formatting if you wish. You can also use special formatting—such as italic text—as a visual cue to your reader that they are reading a flashback. You might use this formatting by itself or in addition to textual indicators. For example: “At the sound of Wilfred’s voice, Bob froze. It was all coming back to him. Wilfred was standing beside him on the corner of 59th and Strauss. An icy, driving rain was falling, and neither of them had an umbrella.” For longer works, such as novels, you can also separate flashbacks into their own chapters, alternating with chapters set in the present timeline.

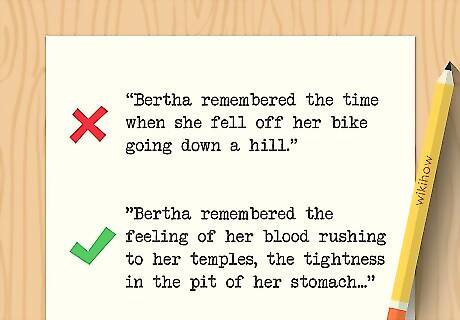

Show, don’t tell, what happens in the flashback. It’s okay to simply summarize past events in your narrative sometimes. A true flashback, however, should be a powerful scene in its own right. Your flashback will be more engaging if it includes specific details, such as the sights, sensations, emotions, and events that the point-of-view character is experiencing. For example, instead of saying, “Bertha remembered the time when she fell off her bike going down a hill,” you could write, “Bertha remembered the feeling of her blood rushing to her temples, the tightness in the pit of her stomach. One moment she was flying down the hill at what felt like an impossible speed. The next, she was in the air, and the hard asphalt was rushing up to meet her.”

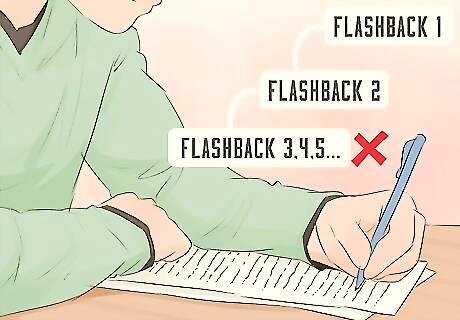

Avoid using too many flashbacks. A lot of flashbacks can bog down the action and leave your reader feeling confused or frustrated. If you’re writing a short story and feel you must include flashbacks, try to select one or two key past moments to focus on. If you’re writing a longer story, such as a novel, make sure to space out your flashbacks between strong, well-developed scenes set in the main timeline.

Using Flashbacks in Screenplays

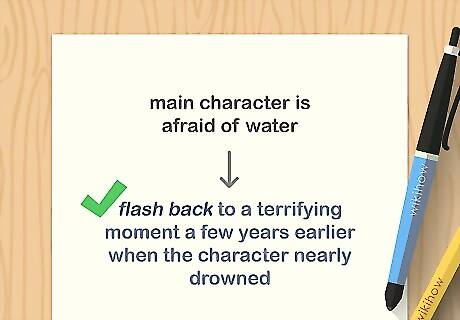

Choose a powerful, important moment as the focus of your flashback. Just like a flashback in prose, a film flashback should support the story and capture the viewer’s interest. On film, it can be even more important to convey information in a clear, concise, and impactful way. You can do this by writing a flashback that focuses on strong actions, sensations, or emotions that your character experienced in the past. For example, maybe your character is afraid of water. You could flash back to a terrifying moment a few years earlier when she nearly drowned. A flashback can also reveal key information about the plot. For example, perhaps your character is a detective at a crime scene. She might see a key piece of evidence, such as a hat left behind by the suspect, and then flash back to a memory of seeing a man wearing the same hat.

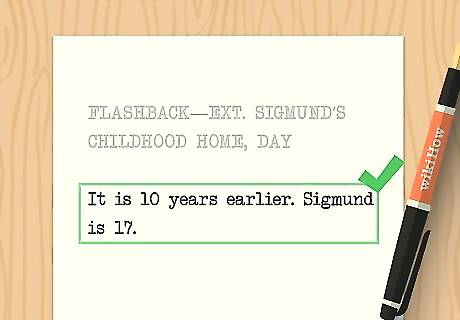

Pinpoint when the flashback takes place. Fine details and strong continuity are crucial in creating a good film. If you’re writing a flashback for a screenplay, it’s important for the director to be able to tell exactly when it is happening relative to the main events of the movie. This will affect things like how much younger the character(s) need look in the flashback, or how different the sets, costumes, and props need to be in order to reflect the time difference. Even if it’s not spelled out explicitly for the audience, you can indicate when the flashback takes place in the script (e.g., after the scene heading, you might say, “It is 10 years earlier. Julio is 17.”)

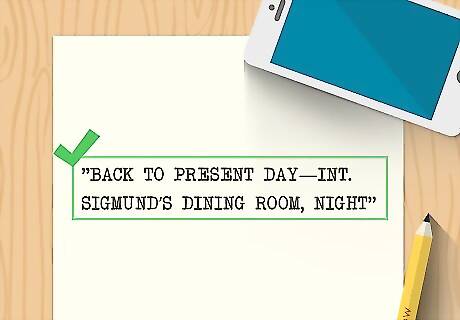

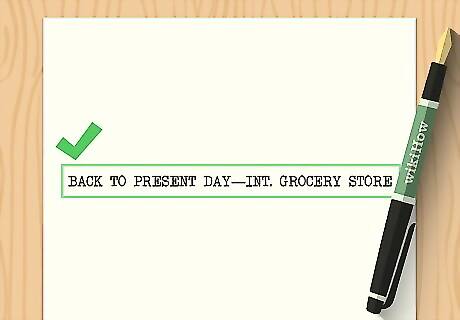

Label your flashback clearly in the script. In order to successfully translate a written flashback to the screen, it’s vital for the director to be able to tell where a flashback begins and ends in a script. While there are many ways to format a flashback in a screenplay, the most important thing is to be clear and consistent. For example, you might start the flashback with a scene heading like: “FLASHBACK—EXT. SIGMUND’S CHILDHOOD HOME, DAY.” Label the end of the flashback, too. You could use a scene heading such as “BACK TO PRESENT DAY—INT. SIGMUND’S DINING ROOM, NIGHT.”

Use visual cues or other devices to set the flashback apart. There are many ways to let your audience know they are seeing a flashback. While some of these might ultimately be up to the director or editor (e.g., making flashback scenes black and white), you can also suggest ways to clarify the nature of the scene as a writer. For example, you might: Include superimposed text to appear on the screen that clarifies the timeframe of the flashback (e.g., “SUPER: Esmond’s 30th birthday, 10 years earlier.”). Describe differences in the appearance of the characters and/or setting that indicate the passage of time. For example, if the main action takes place in summer, a snowy backdrop will clearly indicate that the flashback takes place in a different season.

Establish a clear transition into the flashback. While you can cut suddenly to a flashback if you’re trying to achieve a particular effect, it’s often best to create some kind of smooth transition between present and past scenes. You might have the character focus on an object or image that reminds them of the past, or set up the flashback with a spoken line that references a past moment. For example, your character might see a trout on ice in the grocery store and stop to look at it. The scene then transitions to a memory of a fishing trip where she caught a gigantic trout.

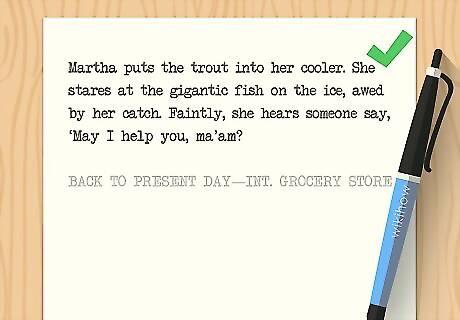

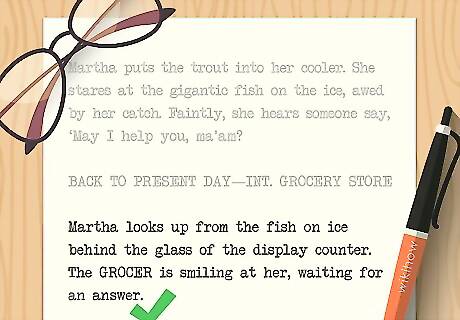

Make a smooth transition out of your flashback as well. It’s also important to have a smooth transition back to present day. It can be helpful to provide some kind of transitional cue (e.g., a voice calling the character, causing them to snap out of their memory and come back to the present). For example: “Martha puts the trout into her cooler. She stares at the gigantic fish on the ice, awed by her catch. Faintly, she hears someone say, ‘May I help you, ma’am?’” BACK TO PRESENT DAY—INT. GROCERY STORE. Martha looks up from the fish on ice behind the glass of the display counter. The GROCER is smiling at her, waiting for an answer.”

Comments

0 comment