views

Today, on 2nd Baisakh, the birth anniversary of Narendrajit Singh of Manipur, we pay tribute to one of the most remarkable heroes of the Freedom struggle who fought alongside the nation in the war of 1857 and led armies in the Cachar region of Assam.

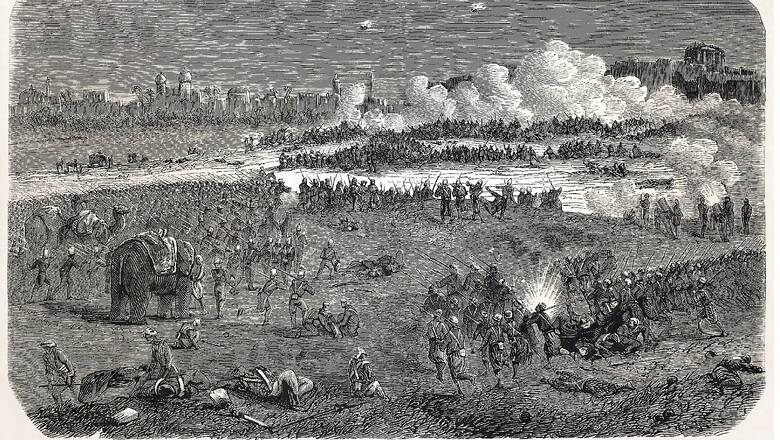

The war of 1857: planning and execution

At Haridwar Kumbh of 1855, culture, strategy, and weapons shook hands and vowed to expel the British from Indian soil. The confluence of Kumbh meticulously planned the first war of Indian Independence of 1857. While imperialist schools of thought believe that the war of 1857 was merely a series of isolated ‘revolt’ or ‘mutiny’ in which the kings and queens participated only for their kingdoms and their territory; excerpts from the correspondence of Capt. Robt. Stewart, (Superintendent of Cachar) paint a very different picture by clearly mentioning the circulation of Chapati and Lotus flowers throughout the country. Thus, acknowledging that the nationwide planning for the war reached as far as Cachar and Chittagong. The myth of isolated uprisings in the country that has been propagated through years and generations crumbles when we put historical evidence under a holistic lens. Under the circumstance of a lack of collective identity, goal and a strong concept of ‘nation’, it would not have been practically impossible to mobilise people from Delhi to Chittagong towards one common goal. It is therefore safe to conclude that the sentiment of one nation flowed in the veins of every Indian.

Such diligence was their planning that the messages of war were conveyed via lotus flowers and chapatis to the farthest and remotest corner of the country and such strong was the urge of self-determination among the people that they agreed to risk everything based on just one message. The Indians recruited in the British Army who were awakened by the call for action knew that the moment they defy orders of the British, they will lose their job, their livelihood, and eventually their lives. Yet, there was an inextinguishable fire in their hearts- the fire called ‘Swa’- that fueled their passion for Swaraj.

Landmark in North-east: Cachar

Historians have also conveniently left out the Northeast of India while documenting this historical landmark. But like the rest of the country, the fire of Swa was ablaze among the people here. A major chapter in this history was that of Cachar where platoons of freedom fighters from different regions converged and collectively fought the British. Today, Cachar is a district located in Southern Assam. In 1857, it was a region that was a part of the British occupied domains of India and a very important administrative center. There is no second opinion about the fact that this above-mentioned movement towards Cachar began from Chattagram or Chittagong hills (currently situated in Bangladesh, south of the Indian state of Tripura) by the awakened members of the 34th native infantry, on 18th November 1857. To date, there is no official documentation of the names or even the exact number of soldiers that took part in this war for Independence; some historians believe the number was 300 while others argue that the number was nearly 400-450.

The 34th Native Infantry of Chittagong

As per records, it all started on 18th November 1857, at 9-10 pm when the guards posted at the collector’s office began firing rounds and thereafter released prisoners from the Chittagong jail. These released prisoners too joined the movement for independence. Simultaneously, the British armory was attacked by the Indians from where surplus arms and ammunitions were procured. Thereafter, as planned, they attacked the treasury and collected Rs. 2,78,267 and resumed their march in two separate branches- one towards Tripura and another towards Cachar via Lushai hills. Lt. Ross in his reports mentions that the 34th Native Infantry had used careful strategy and split their platoon into smaller segments and took the forest route to reach Cachar. The branch that had taken the Aizwal-Silchar route to reach Cachar, was helped by local Lushai chiefs (who were also known as Sailo) from the Lushai Hills (in present-day Mizoram). The British had assumed that Indian patriots could be bought off with money and thus Capt. Stewart made a failed attempt of luring the local chiefs to his side by promising Rs 50/- to them for every Indian soldier fighting against the British that they killed or captured (to put this in perspective, at that time gold price was Rs 2 per Tola – 10 grams). This offer was accompanied by a stern warning that the freedom fighters must not be helped.

Contrary to what Capt. Stewart must have expected, the Lushai chiefs and common people alike helped them in whatever capacity they could. The branch moving towards Tripura was led by Rajabali Khan and had to take shelter in the hilly areas of Comilla (Presently a border town in the Chittagong division of Bangladesh) after having been intercepted at Tripura by the British. This was the period when these soldiers of Indian soil faced the most difficulties. Their ration stockade had been destroyed during the skirmish at Tripura, they had been isolated in the thick jungles leading to Cachar where they had to sustain themselves in adverse situations but they were helped by local people despite the British warnings. Thus, after having been replenished, the troops moved upward from Comilla to Latu (currently a town in the Karimganj district of Assam sharing borders with Bangladesh). At Latu, their movement was intercepted by Captain Byng who confronted them along with 150 soldiers. A battle was fought at Latu on 19th December 1857 and marked a major victory for the freedom fighters as they were able to kill Capt. Byng and crush his platoon. C E Buckland records that after this battle the winning party motivated the troops of Capt. Byng to renounce the British service and join the movement.

Leadership of Narendrajit Singh

At the same time, a Prince of the Manipur royal family Shri Narendrajit Singh was also active in his own capacity in Cachar. He was sent to Decca jail by the British in 1841. He was born on 2nd Baisakh, 1741 Saka (1819) to Chourjit Singh; the ruling king of eastern Cachar. Narendrajit was a vigilante and observed the British interference in his kingdom very closely. The bottled-up resentment of the unwanted and unwelcomed intrusion took physical form in 1834 when his elder brother Tirbhubanjit Singh led a battle against the British and the subservient Manipur Kings who were bowing to the whims of foreigners and was mercilessly killed during the same. Narendrajit Singh followed the footsteps of his brother and joined the movement until he was captured in 1841. He was kept under surveillance in Decca for 10 years and was later released in 1851. During this period, the prince got acquainted with the then Indian politics along with the resources, capabilities and strategies of the British. All this injustice towards his people taught him that until and unless a united Indian power confronted the British, their rule in India would not end. Hence, after the war of 1857 was planned at Kumbh, and Narendrajit Singh received intel, he began his endeavor to blow strikes on the British empire.

According to his plan, he helped 6 other Princes of Manipur in escaping the British jails on 10th January 1858. After being released from Decca jail, Narendrajit Singh was living in Cachar where he also mobilised the people of Manipur and Cachar alike. His influence was so great that when the British instructed the king of Manipur to dispatch 400 troops to fight alongside them in 1857 and the King also agreed under pressure, the common people and the soldiers of Manipur refused to join the British serving troops. Based on the guidance of Narendrajit Singh they had two arguments for rejecting the British offer- a) they believed in the brotherhood of Indians and recognized the power of patriotism b) they believed that it was sinful to fight for the foreigners who had encroached upon their territory.

Combined Attack

When the 34th Native Infantry heard of Narendrajit Singh and his leadership, they decided to join hands with him and unite their forces. Hence, after the battle of Latu on 19th December 1857, they entered Cachar on 20th December and met Narendrajit Singh and his followers. They launched a combined attack on the British at Binnakandi (currently a town in the Cachar district of southern Assam). As the freedom fighters had strategized well, they could engage with the British at several fronts; this collective launch of attack by them gave a tough time to the British at Cachar, Mohanpur, Binakandi, Latu, Jalingah, Govindnagar, and parts of Manipur. The leader of the movement; Narendrajit Singh was injured during the battle of Binnakandi on 12th January 1858 by the British troops of Sylhet light Infantry led by Lt Ross. Narendrajit Singh was then carried into the forest of Manipur from where the king of Manipur Chandra Kirti Singh had managed to shift Narendrajit Singh to the royal palace despite the British pressure on 2nd February 1858. The king was totally against surrendering his kin to the British; they engaged in a series of back and forth over the custody of Narendrajit Singh, but eventually the British got the upper hand and Chandra Kirti Singh had to surrender him on 25th April 1858. After a show of trial, the British decided to send the leader of 1857 to Andaman for life transportation on 25th June 1858.

Narendrajit was an exceptional leader and patriot who despite being banished from his own land and suffering 10 years of wrongful captivity (From 1841 to 1851) managed to have sharp a sense of judgement, observation and leadership. He could mobilise people, inspire them, and take them on the rightful path of freedom which is probably why the British tried to keep him as far away from his people as possible. Despite being in Decca jail for ten years, he never lost sight of what his country needed. To prevent any further influence of Narendrajit Singh on the people, the British had to send him to Andaman as he was able to keep the fight going on for a much longer period than the British had expected and the leaders in North India could sustain. Narendrajit Singh is a name that disappears from the British records after 1858 but his name today is engraved in our history as one of the greatest freedom fighters; his relics (including a handwritten copy of the Bhagwad Gita and a few other personal belongings) have been preserved and revered by his descendant Shri Birendrajit Singh in Agartala, Tripura. These are displayed only once every year on Narendrajit Singh’s Birth Anniversary. The troops of the 34th native Infantry that left Chittagong had no clue of Narendrajit Singh until 19th December and yet they fought proudly under his leadership in Cachar and Binnakandi because they believed that this Prince of Manipur could lead them to victory, and he did. This is not the story of some unsung heroes, this is the legend of people whose names have been conveniently omitted from the process of documentation, and thereof from our history. The warriors of the 34th native Infantry, the Lushai chiefs and every single individual who contributed to the freedom struggle are the spark of Swaraj that lights our lives up till today.

Anandita Singh is a Researcher at the Centre for Northeast Studies. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment